A Letter from Matinicus - Monarchs

What sort of year for Monarchs?

By Eva Murray

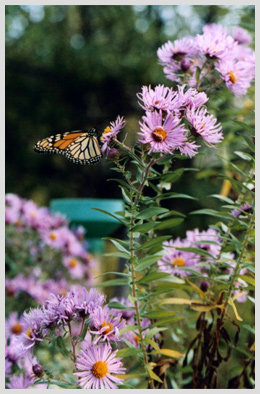

Monarch butterfly on purple asters.

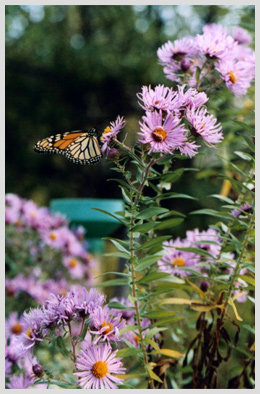

Monarch butterfly on purple asters.

Photo by Gretchen Piston OgdenI was clever enough, back in 1989, to marry a man who owned a house on the island of Matinicus with a big patch of milkweed in the dooryard. Now, with both kids residing on the mainland for the most part, I am subject to all sorts of pleasant flashbacks to my first season in this house. I had taught at the island's one-room school for one year, with my acceptance letter to graduate school, deferred for that teaching year at my request, still in hand. I never went. The following September I closed out my South Thomaston post office box and returned to Matinicus to live on the butterfly ranch.

The life cycle of the monarch butterfly is well known. Many of us have dropped a fat caterpillar and a rough fistful of milkweed leaves into a jar, in the interests of science. The caterpillar eats milkweed leaves until it's a couple of inches long and fat as a cute little wormy-looking thing can get, and then somehow it knows it is time.

The caterpillar locates a suitable spot to hang (sometimes trekking no small distance in the process), attaches itself with a blob of some very adequate cement, forms a sort of letter” J” with its body, and at some point when everybody's back is turned, it wraps itself in a highly fashionable bright apple-green chrysalis, with a metallic gold belt and additional sequins. There it will hang, on the plant, from the jar lid, or decorating any truck bumper, plow frame, wheelbarrow, go-kart, or stepladder in the area, while mysterious processes take place inside.

A hungry caterpillar goes about the business

A hungry caterpillar goes about the business

of munching milkweed leaves.

Photo by Jennifer W. McIntoshWhen the time comes right, most of these little shelters will burst open and a relatively helpless, somewhat disoriented butterfly will emerge, wings squashed, abdomen oversized, and colors incredibly new and sharp. The little thing lights on some nearby object, even a blade of grass, and stretches, fills, expands and dries out its new wings. If no watching kittycat gets it before it can fly, eventually takes to the air on an autumn day with a deep blue sky.

With the milkweed patch only about 20 feet from our kitchen door, this whole drama took place with us tracking and stumbling through it all...boorish humans who presume to stomp through dinner, move the object from which the chrysalis hangs, keep cats, and attract neighborhood children, many of whom carry those jars with the holes in the lids. We made a concerted effort not to disturb the whole works, feeling rather honored to host the convention of monarchs, but hey, when I need my ladder, I need my ladder. Thus, more than a few of the little cocoons were accidentally dislodged. If they were discovered, they were carefully re-attached to the lowest clapboard of the house with thread and a thumbtack. Usually these rescued ones survived.

The emergence of butterfly from

The emergence of butterfly from

a chrysalis, and then the slow

unfolding and drying of wings

occurs over the course of

an afternoon.

Photos by Martha W. McIntoshThe first time we ever tried this particular act of wildlife rehabilitation was back in August of 1989. I was working on my wedding dress, which, to the consternation of half my neighbors, I purposed to make myself. Paul came inside with a broken-off chrysalis, and said something about he knew he wasn't supposed to see the dress but could he have some thread? I had bought some full-price white thread of better-than-average quality, not that six-for-a-dollar stuff I normally used at that point in my life; the thread held and the butterfly took off, and he's been rescuing chrysalises ever since.

In early summer, when the old monarchs show up to mate and lay their eggs in the milkweed patch, you can tell they've been through a lot. Faded, ragged-edged and frazzled, it's been a long way since Mexico. They fly around the yard, chasing each other, flying in pairs, reminding us that spring never claimed to be all that civilized. Soon, if one were to look very, very carefully, one would see the tiniest caterpillars on the milkweed leaves, usually on the undersides, miniature version of the fat striped ones we recognize, there to do nothing but eat. And eat they do. In a good year, there are hardly any leaves left on the milkweed by mid-September.

When it has been a particularly good year for monarchs, the purple asters which line the dusty autumn roadsides are covered with butterflies, fueling up for the trip. It would seem the 20 miles over water would be trip enough, but that's just the beginning. I do not know exactly where our particular butterflies go, of course, but we hear that there are trees in Mexico and places thereabouts just completely orange, heavy laden with the butterflies of a New England summer. Some have even made the trip from Canada.

I do not know why some years are good years, and some are not. For the past couple of summers before last, we worried about the monarchs. We had begun to think of them as our monarchs. Very few came back, and few left in the fall. Last year, for whatever reason, a great many came back. In the late spring, the dooryard was full of court and spark, and by late summer, the lowest clapboard of the house along the side toward the milkweed patch was hung with 26 chrysalises.

Monarch butterfly on purple asters.

Monarch butterfly on purple asters.Photo by Gretchen Piston Ogden

A hungry caterpillar goes about the business

A hungry caterpillar goes about the businessof munching milkweed leaves.

Photo by Jennifer W. McIntosh

The emergence of butterfly from

The emergence of butterfly froma chrysalis, and then the slow

unfolding and drying of wings

occurs over the course of

an afternoon.

Photos by Martha W. McIntosh

Martha W. McIntosh lives in Lincolnville. She and her daughter Jennifer learned about monarchs in the mid-1970s at the Terrell School in Camden, where witnessing the transformation of caterpillar to butterfly became an annual ritual.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.