Tollef Runquist: A Painter Follows His Bliss

Maine and family fuel a fearless artist

By Carl Little

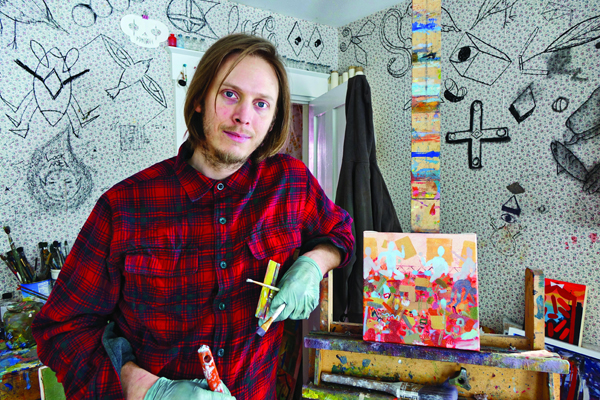

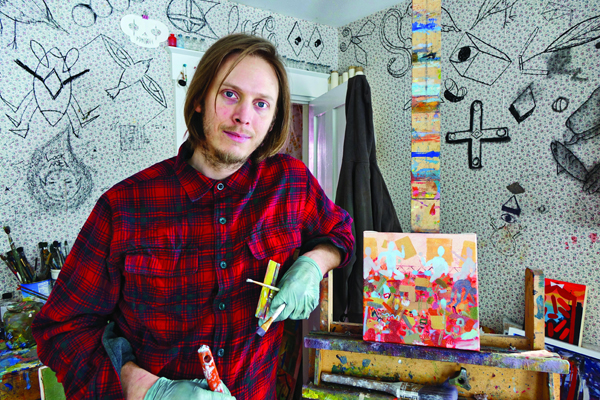

Photo by Sandy Dolan. Tollef Runquist in his Searsport studio, a sanctuary where he explores a range of aesthetic possibilities.

Photo by Sandy Dolan. Tollef Runquist in his Searsport studio, a sanctuary where he explores a range of aesthetic possibilities.

By Carl Little Artist Tollef Runquist lives with his nine-year-old son, Shiloh, in a home filled with paint and boy things. A variety of toys—LEGOs, stuffed animals, and cars—are strewn on a rug in their house just off Route 1 in Searsport. In the studio, which Runquist said had been cleaned up a bit for this visitor, paintings large and small hang and stand stacked around the room, with some sketches drawn directly on the walls. An easel barely anchors the space. Given the time they spend together, it’s not surprising that Shiloh’s pursuits have helped inspire his father’s artistic vision, especially since much of Runquist’s work is based on place and experience. The painter has integrated his son’s playthings—the LEGOs, Styrofoam swimming “noodles,” a geodesic jungle gym, a sandbox—into his recent canvases, capturing a wonderful unruliness in the process. Paintings courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

The Klimt-esque Happy Melody,

oil on canvas, 30" x 30", is infused with color

and a Maine coast feel.

Runquist loves the freedom represented in child’s play. When he goes to Searsport Elementary School to pick up Shiloh, he admires the children’s drawings that hang in the hallway. “They’re so wildly imaginative,” Runquist said, “unencumbered by experience or bias.”

He strives for this liberation in his work.

Runquist grew up in a home filled with art. His parents were collectors, bringing home paintings and sculptures from travels and hanging work by friends. Some of the paintings were by his father. A Swedish émigré, Bjorn Runquist was head of the modern language department at Kent, a college preparatory school in Connecticut, but he also painted. “[My father] was fond of saying that when the teaching was driving him crazy, the painting would keep him sane—and the opposite as well,” Tollef recalled.

While he never took formal lessons from his father, Tollef spent time in his studio watching him paint. He came to appreciate the discipline, as well as the ups and downs of the creative process, the frustration and the jubilation. These days, father and son co-teach plein air painting workshops in the summer on Clark Island, in Spruce Head.

Now a seasoned painter himself, the younger Runquist undergoes a similar catharsis when he paints, giving himself to the canvas as he works through ideas. Over time, the studio has become a kind of sanctuary, “full of possibility.”

Paintings courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

The Klimt-esque Happy Melody,

oil on canvas, 30" x 30", is infused with color

and a Maine coast feel.

Runquist loves the freedom represented in child’s play. When he goes to Searsport Elementary School to pick up Shiloh, he admires the children’s drawings that hang in the hallway. “They’re so wildly imaginative,” Runquist said, “unencumbered by experience or bias.”

He strives for this liberation in his work.

Runquist grew up in a home filled with art. His parents were collectors, bringing home paintings and sculptures from travels and hanging work by friends. Some of the paintings were by his father. A Swedish émigré, Bjorn Runquist was head of the modern language department at Kent, a college preparatory school in Connecticut, but he also painted. “[My father] was fond of saying that when the teaching was driving him crazy, the painting would keep him sane—and the opposite as well,” Tollef recalled.

While he never took formal lessons from his father, Tollef spent time in his studio watching him paint. He came to appreciate the discipline, as well as the ups and downs of the creative process, the frustration and the jubilation. These days, father and son co-teach plein air painting workshops in the summer on Clark Island, in Spruce Head.

Now a seasoned painter himself, the younger Runquist undergoes a similar catharsis when he paints, giving himself to the canvas as he works through ideas. Over time, the studio has become a kind of sanctuary, “full of possibility.”

The “toy paintings” contain an element of the

whimsical, such as in Afterglow,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

Runquist was creative from an early age, drawing and then painting. Before he graduated from Kent in 1998, he had already had his first solo show, at the Paris New York Kent Gallery, owned by the famed New York City “absurdist furrier” Jacques Kaplan (he was known for mixing art and fur in his family’s fur business), who had moved to Kent in the early 1980s to run a gallery. Runquist furthered his art knowledge and studio skills at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, earning a BFA in 2002. After a year in New York City, he moved to Maine.

Runquist had first visited the state as a youngster, when his parents bought land in St. George in the 1980s. For the first few summers the family slept in a tent; they later assembled a Grossman’s Lumber storage shed and installed bunk beds for the five of them (Tollef has two younger sisters, Carla and Sophie). There was no electricity, running water, or television.

“I fell in love with Maine,” says Runquist. “I didn’t realize it at the time—I was a child—but it was beautiful and wonderful.” Maine felt more like home to him than other places, so it made sense to settle here, first in Rockland and then Searsport.

The “toy paintings” contain an element of the

whimsical, such as in Afterglow,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

Runquist was creative from an early age, drawing and then painting. Before he graduated from Kent in 1998, he had already had his first solo show, at the Paris New York Kent Gallery, owned by the famed New York City “absurdist furrier” Jacques Kaplan (he was known for mixing art and fur in his family’s fur business), who had moved to Kent in the early 1980s to run a gallery. Runquist furthered his art knowledge and studio skills at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, earning a BFA in 2002. After a year in New York City, he moved to Maine.

Runquist had first visited the state as a youngster, when his parents bought land in St. George in the 1980s. For the first few summers the family slept in a tent; they later assembled a Grossman’s Lumber storage shed and installed bunk beds for the five of them (Tollef has two younger sisters, Carla and Sophie). There was no electricity, running water, or television.

“I fell in love with Maine,” says Runquist. “I didn’t realize it at the time—I was a child—but it was beautiful and wonderful.” Maine felt more like home to him than other places, so it made sense to settle here, first in Rockland and then Searsport.

Runquist’s interest in textile design is evident

in Window #6, oil on board, 8" x 10".

The coastal surroundings had an impact on Runquist’s art. While the first critical attention he received related to largish abstracts—ambiguous figures in ambiguous spaces—his work these days has a strong connection to place. While not as site-specific as the landscapes of his father, these scenes have a recognizable Maine coast feel to them: the geometric solidity of houses, streets leading to the sea, a working dock.

“I’m less inspired by particulars of place or time of day or facets of light than I am in [translating] experience,” Runquist noted. While striving to allow more “imaginary aspects” into his work, he continues to respond to the landscape, relishing the mixture of the architectural with the natural that exemplifies New England.

“Something about Maine,” Runquist has written, “resonates with my need for solitude as an artist.”

The state’s rural geography helps satisfy that need. “There is quite a bit of wildness and distance here,” he points out; “This is fertile ground for many temperaments.”

Runquist approaches his subjects from an abstract perspective, drawing on his passion for such non-representational masters as Willem de Kooning, Gustav Klimt, and Richard Diebenkorn. In Runquist’s wonderful Yard Sale Banquet, the offerings on a lawn are transformed into an impasto invention of color strokes.

Often he finds his subject close at hand: images of curtains are based on Runquist’s immediate milieu. There’s a touch of Maine and New York painter Lois Dodd here, both in subject matter and the abstract rendering of it. But the feeling is more psychological, especially when the curtains appear to dissolve.

Runquist’s interest in textile design is evident

in Window #6, oil on board, 8" x 10".

The coastal surroundings had an impact on Runquist’s art. While the first critical attention he received related to largish abstracts—ambiguous figures in ambiguous spaces—his work these days has a strong connection to place. While not as site-specific as the landscapes of his father, these scenes have a recognizable Maine coast feel to them: the geometric solidity of houses, streets leading to the sea, a working dock.

“I’m less inspired by particulars of place or time of day or facets of light than I am in [translating] experience,” Runquist noted. While striving to allow more “imaginary aspects” into his work, he continues to respond to the landscape, relishing the mixture of the architectural with the natural that exemplifies New England.

“Something about Maine,” Runquist has written, “resonates with my need for solitude as an artist.”

The state’s rural geography helps satisfy that need. “There is quite a bit of wildness and distance here,” he points out; “This is fertile ground for many temperaments.”

Runquist approaches his subjects from an abstract perspective, drawing on his passion for such non-representational masters as Willem de Kooning, Gustav Klimt, and Richard Diebenkorn. In Runquist’s wonderful Yard Sale Banquet, the offerings on a lawn are transformed into an impasto invention of color strokes.

Often he finds his subject close at hand: images of curtains are based on Runquist’s immediate milieu. There’s a touch of Maine and New York painter Lois Dodd here, both in subject matter and the abstract rendering of it. But the feeling is more psychological, especially when the curtains appear to dissolve.

Items for sale take on an element of the

abstract in Yard Sale Banquet,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

“I’m building a composition or composing a song,” Runquist said, “but it happens to be visual.”

The painter is prolific; at any given time he may be working on five things. He thrives on experimenting—and recycling. His “Lidface” series consists of peanut butter jar, coffee cup and other leftover covers repurposed into simple expressive outlines of faces, somewhat Picasso-esque in their simplicity of line.

The paintings in a group Runquist calls “Reworked” originated in a need to conserve materials “because you know canvas and stretchers are expensive,” he explained. Taking paintings that for one reason or another he is not happy with or hasn’t been able to resolve satisfactorily, he paints new ideas into them—an abstract pattern over a landscape, for example.

One feels with Runquist that he is fearless when it comes to making art. Like fellow midcoast Maine painter Gideon Bok, he is not afraid of making mistakes—indeed, he often leaves them in. At the same time, if he starts to feel too comfortable with a painting or finds himself getting nervous about making a mistake, he will “throw some paint at it” to break the spell and make for a more dynamic image.

“When I finally let go,” Runquist said, “that’s when I make a breakthrough, that’s when a painting really starts to work.” And he often challenges himself: a handsome set of moonlit nocturnes came out of a desire to explore a darker, more restrained palette.

Runquist has established relationships with two galleries that believe in his work and offer him the flexibility to pursue new ideas: Dowling-Walsh in Rockland, Maine, and the Ober Gallery in Kent, Connecticut. Jake Dowling and Rob Ober have given him several one-person shows in recent years. Ober, Tollef’s history teacher at Kent, was his first collector, purchasing several canvases at a time when he was trying to come up with the cash for a rental in New York City.

The only way to grow as an artist, said Runquist, is “to continue to pursue those things that call you out like beacons.” He cited Joseph Campbell’s famous credo, “Follow your bliss,” but quickly qualified it: “Not in the sense of follow whatever makes you feel good, but those things that deeply tug at you in a way that it’s an imperative to follow them.” Such a journey, he explained, will “take you where you need to go… It might be a little bit bumpier, but in the end it will be worth it.”

Carl Little’s most recent book is William Irvine: A Painter’s Journey (Marshall Wilkes).

Tollef Runquist is represented by Dowling-Walsh Gallery in Rockland and the Ober Gallery in Kent, Connecticut. He also maintains a website, www.tollefrunquist.com.

Items for sale take on an element of the

abstract in Yard Sale Banquet,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

“I’m building a composition or composing a song,” Runquist said, “but it happens to be visual.”

The painter is prolific; at any given time he may be working on five things. He thrives on experimenting—and recycling. His “Lidface” series consists of peanut butter jar, coffee cup and other leftover covers repurposed into simple expressive outlines of faces, somewhat Picasso-esque in their simplicity of line.

The paintings in a group Runquist calls “Reworked” originated in a need to conserve materials “because you know canvas and stretchers are expensive,” he explained. Taking paintings that for one reason or another he is not happy with or hasn’t been able to resolve satisfactorily, he paints new ideas into them—an abstract pattern over a landscape, for example.

One feels with Runquist that he is fearless when it comes to making art. Like fellow midcoast Maine painter Gideon Bok, he is not afraid of making mistakes—indeed, he often leaves them in. At the same time, if he starts to feel too comfortable with a painting or finds himself getting nervous about making a mistake, he will “throw some paint at it” to break the spell and make for a more dynamic image.

“When I finally let go,” Runquist said, “that’s when I make a breakthrough, that’s when a painting really starts to work.” And he often challenges himself: a handsome set of moonlit nocturnes came out of a desire to explore a darker, more restrained palette.

Runquist has established relationships with two galleries that believe in his work and offer him the flexibility to pursue new ideas: Dowling-Walsh in Rockland, Maine, and the Ober Gallery in Kent, Connecticut. Jake Dowling and Rob Ober have given him several one-person shows in recent years. Ober, Tollef’s history teacher at Kent, was his first collector, purchasing several canvases at a time when he was trying to come up with the cash for a rental in New York City.

The only way to grow as an artist, said Runquist, is “to continue to pursue those things that call you out like beacons.” He cited Joseph Campbell’s famous credo, “Follow your bliss,” but quickly qualified it: “Not in the sense of follow whatever makes you feel good, but those things that deeply tug at you in a way that it’s an imperative to follow them.” Such a journey, he explained, will “take you where you need to go… It might be a little bit bumpier, but in the end it will be worth it.”

Carl Little’s most recent book is William Irvine: A Painter’s Journey (Marshall Wilkes).

Tollef Runquist is represented by Dowling-Walsh Gallery in Rockland and the Ober Gallery in Kent, Connecticut. He also maintains a website, www.tollefrunquist.com.

Photo by Sandy Dolan. Tollef Runquist in his Searsport studio, a sanctuary where he explores a range of aesthetic possibilities.

Photo by Sandy Dolan. Tollef Runquist in his Searsport studio, a sanctuary where he explores a range of aesthetic possibilities.By Carl Little Artist Tollef Runquist lives with his nine-year-old son, Shiloh, in a home filled with paint and boy things. A variety of toys—LEGOs, stuffed animals, and cars—are strewn on a rug in their house just off Route 1 in Searsport. In the studio, which Runquist said had been cleaned up a bit for this visitor, paintings large and small hang and stand stacked around the room, with some sketches drawn directly on the walls. An easel barely anchors the space. Given the time they spend together, it’s not surprising that Shiloh’s pursuits have helped inspire his father’s artistic vision, especially since much of Runquist’s work is based on place and experience. The painter has integrated his son’s playthings—the LEGOs, Styrofoam swimming “noodles,” a geodesic jungle gym, a sandbox—into his recent canvases, capturing a wonderful unruliness in the process.

Paintings courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

The Klimt-esque Happy Melody,

oil on canvas, 30" x 30", is infused with color

and a Maine coast feel.

Paintings courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

The Klimt-esque Happy Melody,

oil on canvas, 30" x 30", is infused with color

and a Maine coast feel.

The “toy paintings” contain an element of the

whimsical, such as in Afterglow,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

The “toy paintings” contain an element of the

whimsical, such as in Afterglow,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

Runquist’s interest in textile design is evident

in Window #6, oil on board, 8" x 10".

Runquist’s interest in textile design is evident

in Window #6, oil on board, 8" x 10".  Items for sale take on an element of the

abstract in Yard Sale Banquet,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

Items for sale take on an element of the

abstract in Yard Sale Banquet,

oil on canvas, 20" x 20".

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.