Beyond the Black Lines

Swimmers find freedom and beauty on the open water

Photographs by Heather Perry

A swimmer heads out at the start of the 2015 Islesboro crossing from Lincolnville to Islesboro, which benefits LifeFlight of Maine. The three-year-old event has become so popular that the limited numbers of entry spots fill up well in advance.

A swimmer heads out at the start of the 2015 Islesboro crossing from Lincolnville to Islesboro, which benefits LifeFlight of Maine. The three-year-old event has become so popular that the limited numbers of entry spots fill up well in advance.

It was just about when I lost all feeling in both feet that I was so overcome with the beauty and singularity of the moment that I stopped moving forward, took my goggles off and slowly twirled around in wonderment. I was treading water in the middle of western Penobscot Bay as that fiery orange star of ours climbed past the horizon. Woo-hoo! I mean, who gets to do that—reach the middle of one of the contiguous 48 states’ coldest bays by swimming just as the sun rises?

An open water swimmer does, that’s who.

Since I was in the middle of a race and quickly slipping to third place as a protégé passed me, I allowed myself just the one holler and a quick “I love you” to my wife, who was paddling my safety boat, before getting back into the swim of things. I was, however, thrilled through my thick wetsuit to the core of my amphibious existence—doubly so since nary a shark had mistaken me for an injured, flailing seal. Previously, the most I’d ever tackled in the 60-degree waters was a mile and I’d peered suspiciously into the murky depths the entire time.

Long before I scrambled up Islesboro’s barnacle-encrusted rocky shore to finish the first annual Lincolnville-to-Islesboro fundraiser swim for LifeFlight of Maine, I felt victorious.

The 3.1 mile Islesboro crossing is one of the longest open water swims in New England. Each swimmer must be accompanied by a friend in a kayak or other small boat. This year’s event raised more than $115,000 for LifeFlight of Maine, which provides critical care transport via helicopter.

The 3.1 mile Islesboro crossing is one of the longest open water swims in New England. Each swimmer must be accompanied by a friend in a kayak or other small boat. This year’s event raised more than $115,000 for LifeFlight of Maine, which provides critical care transport via helicopter.

When I was a child, I wanted to change the world. Not in a scary megalomaniacal way, but in a useful, day-to-day manner. Instead of getting to Point B from Point A by walking, riding, or driving, I dreamed of a day we’d swim places via “sideswims” (as in sidewalks)—narrow rivulets of blue connecting all my favorite spots and making them accessible by my favorite form of transportation. Although I’ve grown up, somewhat, and mostly given up on the sideswim revolution, I have found a way occasionally to live out my old fantasy: open water swimming.

Maine is an open water swimmer’s mecca with its abundance of clear, clean, crisp bodies of water. Each summer more and more people are taking to them. Not too far back, the only open water swim in Maine was Peaks-to-Portland. Now there are events throughout the state, from the Sebago Lake Challenge to MDI’s Echo Lake race to the Islesboro Crossing for LifeFlight in Penobscot Bay. This past summer, in the third year of the Lifeflight event, 80 people made the swim. Earlier in the summer 344 people swam the 2.4 miles between Peaks and Portland.

Matt Montgomery, a Maine swimming coach and the Age-Group Chair for USA Swimming in Maine, said this state has become known nationally for its swimming venues. “Maine is the next frontier for open water swimming in the U.S.,” he said.

To me, there’s no surprise in any of this, although I am a tad biased. I’ve been swimming since I fell in the pool at 11 months, was rescued, and minutes later crawled back in. I’ve been racing since I was 5. At age 45, I thought I was still good enough to qualify for the Olympic trials in swimming (no not the geriatric Olympics, the real ones). I love swimming—the way water ripples down my body, water’s touch, and its feel.

“I am sure no adventurer nor discoverer ever lived who could not swim,” claimed Annette Kellerman, a British music-hall star and open water swimming performer of the early 1900s. “Swimming cultivates imagination; the man with the most is he who can swim his solitary course night or day and forget a black earth full of people that push,” said Kellerman.

Author Hodding Carter, right, talks to Bates College swim coach Peter Casares before the start of this year’s Islesboro crossing. Most open water swimmers choose to wear wetsuits for the swim, which takes anywhere from an hour to two and a half hours.

Author Hodding Carter, right, talks to Bates College swim coach Peter Casares before the start of this year’s Islesboro crossing. Most open water swimmers choose to wear wetsuits for the swim, which takes anywhere from an hour to two and a half hours.

Unlike pool swimming, open water swimming has only distant boundaries, no walls and, most important of all, NO BLACK LINE, the eventual bane of every swimmer’s existence. Swimming without that ever-present guideline on the bottom of the pool is as appealing as a spontaneous dance in a warm rain shower. Anyone who has done a significant amount of lap swimming or competitive racing learns to dread it; no matter how fast or what stroke or what pool, that line is always there.

Perhaps you have to have paid your dues in a lap pool to appreciate how important a distinction this is, but the ever-present nature of the black line can make me a bit batty. I find myself singing things like, “Just put one hand in front of the other and soon you’ll be swimming ‘cross the bay… Just put one hand in front of the other and soon you’ll be swimming ‘cross the bay… Just put…” For an hour straight.

The insanity immediately rolls away when swimming out in the open. Each passing swell produces new challenges and sights and quite often obstacles to overcome. Once, when I was swimming in a race around Manhattan—I was one of six swimmers who did 4.5 miles each—I swam into both a couch and a used condom. When was the last time you ran into either of those while doing lap after lap at your local pool? Even when the obstacles aren’t quite so colorful, they provide enough distraction to make the time, er, swim by. On a sunny day, each stroke creates mesmerizing whirlpools and eddies that sparkle in the refracted light, fading silently into the surrounding depths as I glide on.

Much like running, open water swimming offers a near-total escape from the modern world. In the water, there are no Instagram updates, texts to respond to, or calls to dodge. It’s just me and nature. For that time I’m immersed in the water, life not only seems more manageable—it is. To get along, all I have to do is stay afloat and keep moving forward.

Much like running, open water swimming offers a near-total escape from the modern world. In the water, there are no Instagram updates, texts to respond to, or calls to dodge. It’s just me and nature. For that time I’m immersed in the water, life not only seems more manageable—it is. To get along, all I have to do is stay afloat and keep moving forward.

Others take to the open seas (and lakes) for equally compelling reasons.

“The thing I love about open water swimming is the unpredictable nature of it: wind, chop, swell, temperature, clarity, and wildlife can all change in the course of a swim. In a time when even our cars are driving themselves, this unpredictability is comforting to me,” said Hopper McDonough, 44, a swimming buddy from Bath, Maine, and owner/operator of SwimVacation.

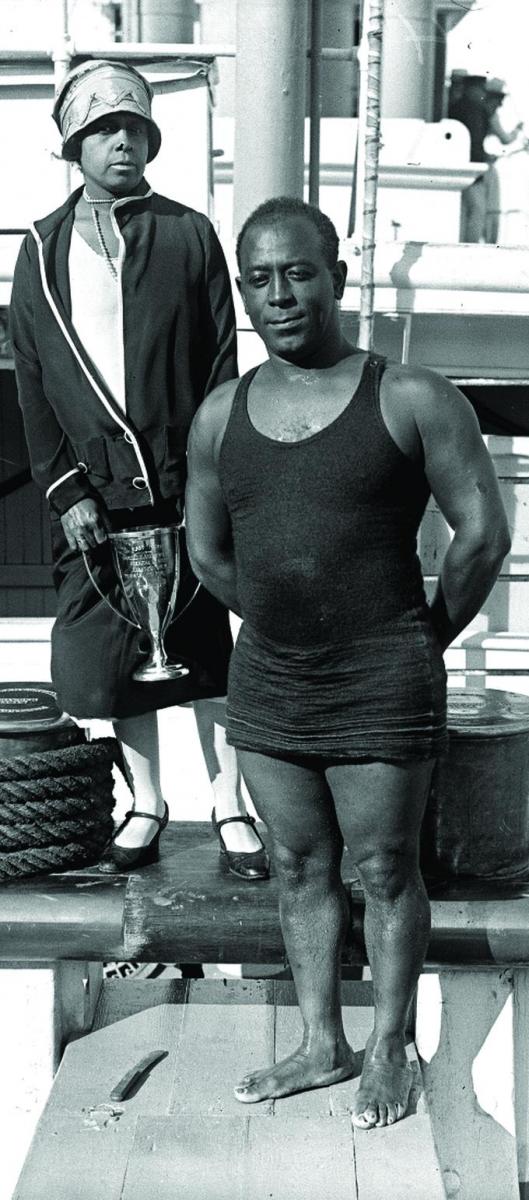

Open water swimming in Maine goes way back. Mitchell Williams won the Portand to Peaks Island swim in 1927. A Portland native and graduate of the Tuskeegee Institute, he is shown here with his wife Florence. Image courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

Open water swimming in Maine goes way back. Mitchell Williams won the Portand to Peaks Island swim in 1927. A Portland native and graduate of the Tuskeegee Institute, he is shown here with his wife Florence. Image courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

Back in 2006, he and I decided to go cruising in the British Virgin Islands. Lacking the necessary funds to charter a yacht, we decided to use our bodies as boats, towing our clothes and sundries behind us on a flagged surfboard. We covered 26 miles in four days, and our undertaking was so unusual that local resort hotels put us up for free on each island we reached. One time, we were even presented with a bottle of rum. It was such a life-altering adventure that Hopper decided to turn it into a business. He leads fellow swimmers, as well as newbies, on swims of various lengths around the islands every spring, inculcating them in one of the major loves of his life. During the day, they swim anywhere from hundreds of yards up to a couple of miles, then at night they wine and dine aboard an accompanying trimaran. It’s been so successful he’s even added weeklong Hawaii trips.

Swimming, and open water swimming in particular, has been around for millenia. In Rome, a person was considered ignorant if he didn’t know how to read or swim. According to the British swimming-memoirist Charles Sprawson, Romans were embarrassed by Emperor Caligula’s inability to swim. Its popularity waxed and waned with the cultural tide. Many feel modern open water swimming saw its rebirth with the British poet Lord Byron’s romantic four-mile crossing of the Hellespont (the waterway that connects the Sea of Marmara and the Aegean Sea) in 1810. Ever since, romantics and realists alike have trained to do the same, as well as to attempt an ever-growing number of other swims. Open water beckons to swimmers much like Mount Everest does to climbers.

In recent years, open water swimming has experienced unprecedented growth in popularity. Think back 20 to 30 years: you might remember seeing one crazy swimmer plodding along in a local lake. Flash forward to now and in those same waters, dozens of swimmers have taken his place. USA Swimming, the governing body of amateur competitive swimming in the United States, does not keep track of open water swimming. However, in England, where swimming trends are similar to our own, membership in the Outdoor Swimming Society grew from 300 in 2006 to 23,000 in 2015. Testament to this trend, the Beijing Olympics included open water events for the first time in the modern games, as has each successive Olympics. The sport even has its own publication: Open Water Swimming magazine is celebrating its second anniversary this year.

At the finish of the Islesboro crossing, swimmers clambered up through the seaweed onto the shore. Although exhausted, just about every competitor was still smiling at the finish.

At the finish of the Islesboro crossing, swimmers clambered up through the seaweed onto the shore. Although exhausted, just about every competitor was still smiling at the finish.

Photographer Heather Perry says she is happiest in, on, or under water. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Smithsonian, The New York Times, and many other national and international publications. She is currently in the middle of a 10 year personal project called Kids in the Hood, which is a daily documentation of the youth in her neighborhood in Bath, Maine. Photo by Polly Saltonstall

Photographer Heather Perry says she is happiest in, on, or under water. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Smithsonian, The New York Times, and many other national and international publications. She is currently in the middle of a 10 year personal project called Kids in the Hood, which is a daily documentation of the youth in her neighborhood in Bath, Maine. Photo by Polly Saltonstall

My thought is that, unlike during much of the 20th century, our ponds, lakes, rivers, and harbors are once again safe enough to use. Hopper agreed. “The major reason the sport is growing in popularity stems from the Clean Water Act,” he said. “For years, the bodies of water closest to our major population centers were so polluted that some would regularly catch on fire.”

Today we can once again swim in places like the Hudson River in New York and Boston’s Charles River, the Great Lakes and San Francisco Bay, and Maine’s Penobscot Bay. While it was never as polluted as its southern cousins, can you imagine going for a nice little swim outside Belfast back when they used to dump tons of rotting chicken parts straight into the harbor? Today, the chicken plants have closed and the bay is much cleaner.

Maine is puddled with clean ponds, lakes, rivers, harbors, and bays simply begging to be swum in. Best of all, when going by water, you can get there from here.

W. Hodding Carter has written for several national magazines, including Esquire, Smithsonian, Newsweek, and Outside. The author of the books Westward Whoa, A Viking Voyage, and An Illustrated Viking Voyage, he lives with his family in Rockport, Maine.

By Hodding Carter | Photographs by Heather Perry

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.