Maiden voyage: the pulling boat in action. It was built from lines

taken off a c. 1919 classic in the collection of the Penobscot Marine Museum.

Scroll down to view a gallery of images.

There is something about the small-boat displays in maritime museums that sets them apart from the rest of the historical collections and galleries. Perhaps it’s the fact that, when it comes to preserving boat collections, the best conditions for the vessels to enjoy their retirement years should be similar to those in which they were built and where they spent their working days when they were out of the water: boat shops and dank and funky storage buildings. These tend to be places with well-worn wooden decks, gravel floors, sunlight filtering through cracks and old windows and perhaps the smell of oakum. The best museums are those that are a lot less concerned with ascots, blazers and felt-covered ropes and more interested in presenting these transportation artifacts in a visitor-friendly way that encourages the patron to not only conjure up how a boat on display was used in the distant past but, maybe, to consider building one and using it today.

One such place is the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, where on the grounds there are several outbuildings that contain outstanding examples of small craft from around the region. Within one such building, sitting on a rack and identified simply as “Pulling Boat—Whitehall style c. 1919,” is a splendid specimen of a early-twentieth-century self-propelled maritime transportation—long, lean, light, and lapstrake. More intriguing is the notation “Thomas Fleming Day, Inc., New York.” Thomas Fleming Day was the founding editor and long-time man-at-the-helm of

The Rudder magazine, which was arguably the first successful boating publication in the United States.

Day started his career as a boat salesman and that experience led him to the conclusion that a publication that catered to the hands-on amateur crowd who wanted to boat themselves was the perfect way to build his market. After 30 years at

The Rudder, promoting practical boating of all sorts, he retired and opened a boat shop on 8th Avenue in Manhattan—commissioning designers and builders to furnish him with stock.

Ben Fuller, curator at the Penobscot Marine Museum, said, “By the time Tom Day was in the shop business he had the benefit of decades of experience. He knew what he wanted for his customers. He could draw on techniques he had seen in dozens of boats.”

The interior finish will be geared toward ease of maintenance.

As to the museum’s example, Fuller continued, “It borrows elements from several styles, producing a rowing boat that’s hard to beat. I can't think of a better small "Whitehall style" boat for a single rower or for that rower to take along a passenger.”

The boat displays an elegant marriage of techniques and influences. It has the long waterline, swooping sheer, and wineglass transom of a Whitehall. It has plenty of narrow lapstrake planks, with a multitude of small frames, wide thwarts, and the tasteful brass strap knees that that evoke the boats of upper New York State. It has a dead flat board keel and, rather than having a traditional Whitehall-style skeg or deadwood, and it is “built down.” In other words, at the stern the planking travels around the transom and then transitions to the stern post—continuing all the way to the bottom of the keel. This forms a well aft and turns the boat into a virtual double-ender. The vessel is relatively narrow (3’6”) for its length (14’), requiring outboard-mounted oarlocks. Indeed, it’s a sports car of a hull that would have been begging to be built if there were plans, which there weren’t.

Many maritime museums face this conundrum—while they have all these grand boats in their collections—boats that provide a treasure trove of visual information about historic design and building techniques—one can’t really tell that much about how a boat actually performed without taking it out for a test spin. Unfortunately, these boats are also valuable artifacts—some are perhaps the sole surviving example of a particular type—and sinking is generally considered a poor conservation technique. The only real way to know what a boat was about is to measure it, document it, draw a set of plans, build a replica that is as close to the original as possible, and then put the replica though its paces.

Time-wise, taking the lines and developing a set of plans can be an expensive process. As boat plans are essentially a set of interlocking topographic maps, the boat has to be “surveyed,” the lines drawn, and the errors reconciled. Then there is the documentation or forensic work—think of it as “CSI Boatyard”—to thoroughly record the victim’s vital statistics through measuring, sketching, photographing, and pattern making. All this is put into the mix to develop a complete construction plan that would allow the mechanic to faithfully fabricate the reproduction. Times and funding being what they are, the Day pulling boat might have remained an interesting but undocumented antiquity—if not for the generosity of the museum's late trustee Ted Leonard who believed the lines needed to be captured and funded the undertaking.

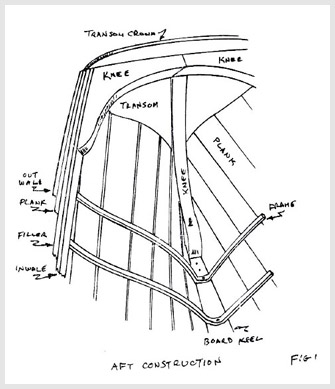

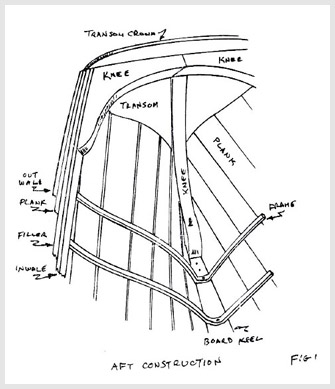

With the lines taken, the next task was to loft (expand) the lines to full scale. Lofting is the crucible in which the bugs are worked out of a set of plans and where the final decisions about the construction details are drawn in. The virtual rabbet is cut into the backbone, the potential bevel on the transom is shaved, the metaphorical fastenings are installed, and the hypothetical woods are selected. Here is where you’ll find out whether you can actually build from the plans you’ve created.

Using the Day boat as an example: What to do about the stem? Judging by the sharp turn, it was likely made of a natural crook of some sort, likely either a branch or root. If a modern-day version were built, a laminated version could be substituted, but here, a Maine-grown hackmatack knee for both the stem and sternpost seemed the appropriate, more authentic choice. The planking drawn onto the lofting indicated that the builder got the maximum possible shape out of the hull that would still allow it to be lapstrake planked. Cedar was the choice here. It is light, rot-resistant, and able to handle a lot of twist along the length of the strake. White oak was chosen for the keel—rugged, durable, and probably what was used in the original. The interior was painted out in the original but, as the hull is so shapely, it would be a good bet that the steamed framing was made of highly pliable elm. Elm, however, is a scarce commodity these days. White oak serves equally well. Maple was a handsome and local candidate for the after seat and transom knees. For the thwarts, mahogany was selected for its good looks and (more importantly) the fact that it was available in the desired width.

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum,

puts the pulling boat through its paces on launch day.

When preparing to build a boat a major decision must be made: whether to set the hull right side up or upside-down. Many elegant and complicated boats were built right-side up with the use of perhaps a single controlling mold (form), and most of the shape determined by the eye of the builder. Of course, no-one knows what method the builder of the original Day boat used, but as both planking and the rather persnickety cutting of the rabbet on its backbone would be a whole lot easier upside-down, that method was chosen. The yeomen work: planking, framing and interior joinery, was done by the students in the "Fundamentals of Boatbuilding" course at the WoodenBoat School. (The very hollow entry and built-down stern made framing the hull a particularly sporty enterprise).

The new boat’s finish, like the original, is designed to be low maintenance—with a semi-gloss Oregon buff paint on the interior and a minimal amount of matte varnish that is easy on the eyes and forgives unintended scratches and indiscretions from, say, enthusiastic canine companions.

“But, how does it perform?” you ask. Sea trials were made in March 2010 on the just-recently ice-free Sebasticook River in Pittsfield. With plenty of high, fast water and turbulence, the boat tracked well, accelerated briskly, felt stable, and balanced well with a passenger in the rear seat. Like a classic roadster, performance will be even better when accompanied by a touch of dignified richness and grace. Even 90-plus years later, Tom Day’s nautical speedster is classy enough for outings of the straw skimmer hat and wicker picnic basket variety. Keep an eye out for it on an upcoming lazy summer afternoon.

INFORMATION:

The plans are available from the Penobscot Marine Museum in digital format. The suggested price is the cost of a museum membership. For information, contact curator Ben Fuller at the museum, 40 East Main Street, Searsport, ME 04974. 207-548-0334;

www.penobscotmarinemuseum.org

Maiden voyage: the pulling boat in action. It was built from lines

Maiden voyage: the pulling boat in action. It was built from lines  The interior finish will be geared toward ease of maintenance.

The interior finish will be geared toward ease of maintenance.

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum,

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum,