A Commoner Who Sailed with Royalty, a Boatbuilder, and a Designer Better Known for His Writing

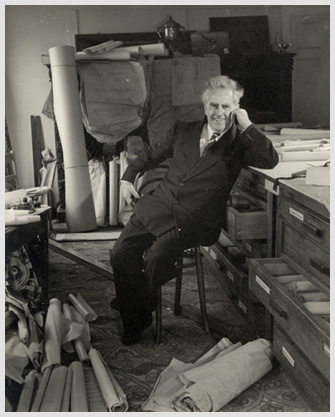

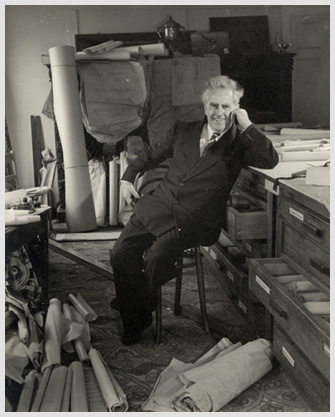

The man of ideas as bon vivant: Uffa Fox at his drafting table.

The man of ideas as bon vivant: Uffa Fox at his drafting table.

Credit: courtesy Tony Dixon and the Classic Boat

Museum, Isle of WightUffa Fox

A commoner who sailed with royalty

Today’s performance sailing world has a few notable characters, but none who can top Uffa Fox when it comes to living one’s life with hairy-chested, two-fisted gusto. Born at the end of the 19th century, dominant in the middle decades of the 20th, Fox set the standard for the working stiff of refinement, the manly man who works with both his hands and his mind, who is as comfortable tossing down pints in the local pub as sipping cocktails in the yacht club, who rubs shoulders with the rich and well-born.

Uffa Fox (1898-1972) was born on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England, and grew up in the town of Cowes, a yachting center. As a young man he served a traditional seven-year apprenticeship with a professional boatbuilder, gaining considerable experience with high-speed powercraft. Then, at age 21, he established his own boatbuilding and design company on the Cowes waterfront.

Fox gained his fame by applying the principles he had learned about fast powercraft to small sailing boats. Considered by many to be the father of the modern planing dinghy, he designed, built, and campaigned an International 14 dinghy that in 1928 took first place in 52 of 57 races he entered. He had similar success with other dinghy classes, such as the National 12 and National 14, and with a series of sliding-seat sailing canoes, including two that he and fellow sailor Roger De Quincy took to America to compete in, and win, the International Canoe Trophy. During World War II, he developed a lightweight, aerodynamic lifeboat that could be slung under an airplane and dropped to aviators who had been forced to ditch in the sea. After the war, he became involved in the design and production of hot-molded sailing craft.

Around the world, Uffa Fox was best known for his joie de vivre. He crossed the English Channel in a sliding-seat sailing canoe, he recorded sea songs, he taught English royalty how to sail, he crewed for the Duke of Edinburgh in sailboat races, and he married three times. Most notably he wrote a series of books of commentary on yacht and small-craft design that were hugely influential when published and continue to be now. Much of the style of the design commentary that has been written in the last few decades owes its inspiration to Uffa Fox’s major works, first published in the 1930s: Sailing, Seamanship and Yacht Design, 1934; Uffa’s Second Book, 1935; Sail and Power, 1936; Racing, Cruising and Design, 1937; and Thoughts on Yachts and Yachting, 1938.

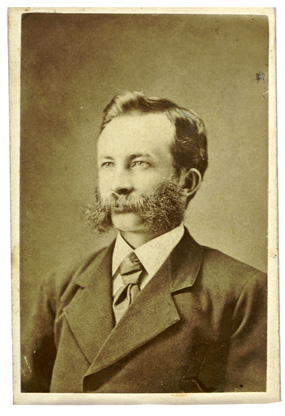

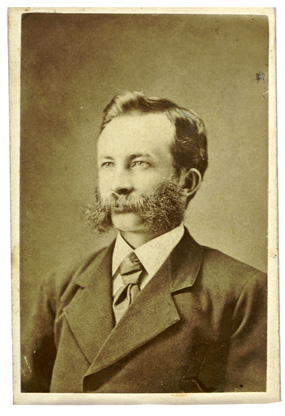

The boatbuilder as gentleman: J. Henry Rushton

The boatbuilder as gentleman: J. Henry Rushton

in the prime of his life. Courtesy St. Lawrence County,

New York, Historical Association collectionJ. Henry Rushton

A boatbuilder with a refined hand and eye

While Uffa Fox in his day was preeminent in the development of small light boats and sailing canoes in England, he was preceded by a boatbuilder and designer in America named J. Henry Rushton of upstate New York. Rushton specialized in making light boats and canoes lighter—so light in some cases that they looked more fragile than an eggshell, but they weren’t—they were light and strong.

Rushton (1843-1906) was born in a small village surrounded by the wilderness of the Adirondack Mountains. He gained his inspiration from the skiffs, canoes, and guide boats that the guides, trappers, and hunters used as a matter of course in making their living. He built his first boat, a canoe, in 1873, after having moved to Canton, New York. Within ten years he was considered to be among the best designers and builders of canoes and other light craft, if not the best.

Rushton was fortunate for his association with George Washington Sears—pen name “Nessmuk”—an outdoor adventurer who wrote for the influential journal Forest & Stream and who cruised the Adirondack waterways in a series of extremely light double-paddle canoes. All five of Nessmuk’s ultralight canoes had been custom built by Rushton; in fact, each man to a great extent built his reputation on that of the other. Nessmuk laid down the specifications; Rushton crafted the boats. Nessmuk took the boats into the Adirondacks to prove their excellence and give them fame through his writings, thus helping to create demand for Rushton to craft more boats.

Rushton’s influence on the then-developing field of canoeing was comparable in scope to that of Nathanael Herreshoff’s on yachting. His influence was so great, in fact, that the ancestries of most double-paddle canoes in use today in this country can be traced back to just a few Rushton models. Which is quite interesting in a way, because not long after Rushton’s death in 1906, his name and work sank into relative obscurity. Until 1968 knowledge of Rushton and his craft was confined to a few enthusiasts who owned surviving Rushton canoes or who had read Nessmuk’s letters in Forest & Stream or Nessmuk’s classic book, Woodcraft.

All that changed in 1968 following the publication of Rushton and His Times in American Canoeing, by Atwood Manley. Right up there in the small-boat hall of fame with American Small Sailing Craft by Howard Chapelle and Canoe and Boat Building for Amateurs by W. P. Stephens, it was a landmark book that not only reestablished Rushton’s reputation but also launched uncounted modern double-paddle canoes. Lots of boatbuilders bought the book and were influenced by Rushton’s refined designs and elegant construction methods. Some built exact copies of the various designs shown in the book, or redesigned the designs to their own preferences, or used the designs as a baseline from which to make a great leap beyond, either in form or in construction technique.

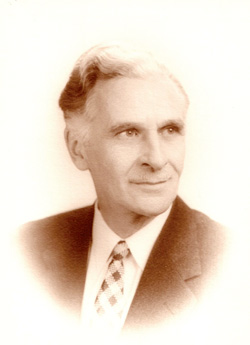

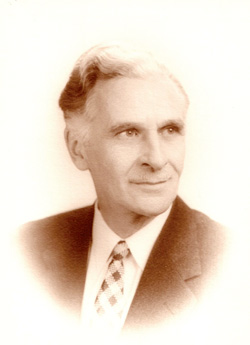

The boat designer as supreme story teller:

The boat designer as supreme story teller:

Weston Farmer in the mid-1950s.

Courtesy Chris (Farmer) BryanWeston Farmer

A designer best known for his writing

There was nothing refined or elegant about the work of Weston Farmer, a journeyman who did his major work—designs that were more “boaty” than “yachty”—in the middle decades of the 20th century. While some of his output continues to have legs, most is forgotten, primarily because the look seems dated to modern eyes.

But design is not the point when it comes to Weston Farmer; rather, it is style—writing style, the way he could tell a story that was more entertaining in its telling than it was in its point.

Born in Minnesota, Earl Weston Farmer (1903-1981)—Weston to his audience, Westy to his friends—served a boatbuilding apprenticeship when he was in his teens and later studied naval architecture and engineering at the University of Minnesota. Over the years he worked in a multitude of design offices—among them, Philip L. Rhodes, Fellows & Stewart, Gibbs Gas Engine, Newport News Shipbuilding, Elco, Annapolis Yacht Yard, and others—before setting up his own practice. Meanwhile he wrote on the side for a number of publications, especially those catering to boating and flying enthusiasts. At one point he was the editor of Modern Mechanics and Inventions magazine.

The zenith of Weston Farmer’s writing career came late in his life during the 1970s, when he wrote a series of articles for the National Fishermen that in effect amounted to a memoir about the good old days. They were eventually collected together in his only book, From My Old Boatshop: One-Lung Engines, Fantail Launches, & Other Marine Delights. Subjects ranged from his memories of some of the best-known American designers of his era—among them John Hanna, William Atkin, Sam Rabl, C.G. Davis, and William Deed—to how to use flotational models as a design tool. His style was that of a stand-up raconteur with an over-the-top ego and irrepressible humor. He was famous for streams of consciousness that went something like this:

“Back in the old days us NAs (that’s short for naval architects) used to sit around the shop (that’s where we worked) keeping our hands warm with Zippo lighters (that’s how we lit our nickel cigars) and waiting for a swell (that’s the guy who paid the bills) to commission us to design a yacht tender that could double as a tomato cooker. Bill Deed, me, Billy Atkin, me, Johnny Hacker, me, Charlie Davis, me, and yours truly were so poor we couldn’t afford coffee filters so we boiled the beans and poured the whole mess through our socks. It was romantic as all getout but you can’t eat romance so Bill and me, Billy and me, Johnny and me, Charlie and me, and yours truly used to fold our waxed linen drafting paper around our socks after we were done draining the coffee and ate that....”

In other words, this wasn’t design. This was entertainment.

Peter Spectre is editor of this magazine and is himself a small-boat enthusiast and story-teller.

The man of ideas as bon vivant: Uffa Fox at his drafting table.

The man of ideas as bon vivant: Uffa Fox at his drafting table. Credit: courtesy Tony Dixon and the Classic Boat

Museum, Isle of Wight

The boatbuilder as gentleman: J. Henry Rushton

The boatbuilder as gentleman: J. Henry Rushton in the prime of his life. Courtesy St. Lawrence County,

New York, Historical Association collection

The boat designer as supreme story teller:

The boat designer as supreme story teller: Weston Farmer in the mid-1950s.

Courtesy Chris (Farmer) Bryan

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

From Whence We Came

Secondary Title Text

Issue 107 - Winter 2010

Sections