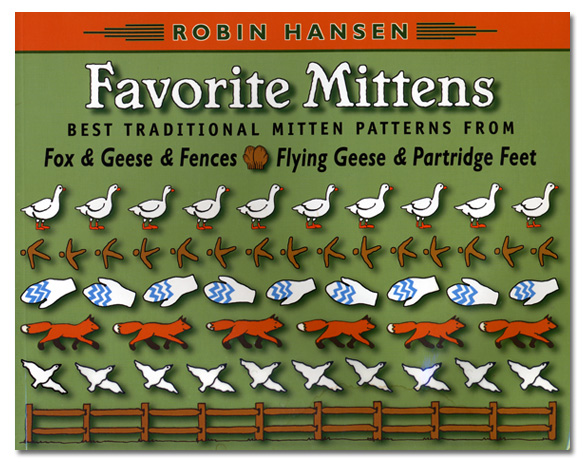

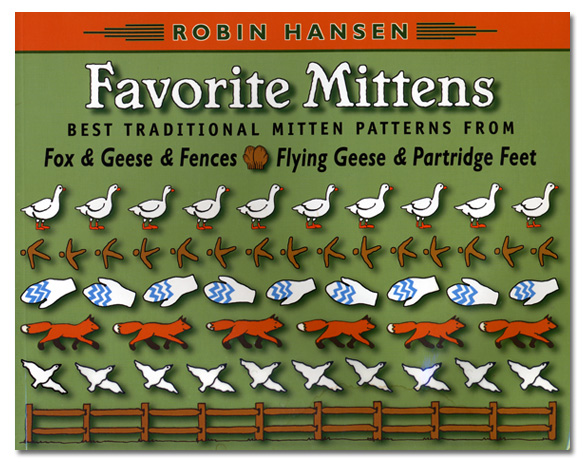

Favorite Mittens: Best Traditional Mitten Patterns from Fox & Geese & Fences and Flying Geese & Partridge Feet

By Robin Hansen

Down East Books, 2005

219 pages, Softcover $21.95

The Mitten as Social History

Robin Hansen earned a doctorate in folklore and folk life from Boston University by collecting traditional knitting patterns and the stories behind them. She gathered them from authoritative sources in New England, the Canadian Maritimes and Scandinavia—from knitters who are grandmothers, fishermen, lumberjacks and farmers, men and women, and who learned them from parents, aunts and neighbors. A decade ago, two collections, from which these instructions were taken, sold more than 48,000 copies, reportedly igniting new interest in the delightful old patterns. Favorite Mittens culls the most popular of these, updated with easier to follow instructions.

More than knitting instructions make this an engaging book, however. Hansen’s fascination with their origins and the techniques used to make them is matched by her respect for the men and women who preserved the craft and willingly shared their knowledge. Her research throughout Maine, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Labrador, Newfoundland, and beyond uncovered the roots of patterns from the British Isles and Northern Europe. Brief oral histories introduce readers to the patterns, often revealing how they came into the knitter’s family, or how designs inspired names like Salt and Pepper, Snowflake, Sawtooth, Peek-a-Boo, or Flying Geese.

“These patterns are as much folklore as songs such as ‘Springfield Mountain’ and ‘Calico Bush,’ as much folk art as patchwork quilt patterns,” writes Hansen. They are also very practical. Many of the patterns were invented to deal with the wind’s insistence on blowing through holes in the knitting rather than around them, notes Hansen. Some call for being felted: they start out huge, are repeatedly washed in hot, soapy water and rinsed in cold until they shrink to fit.

A generation ago, the process of seasoning Chebeague Island Fishermen’s Wet Mittens was more complicated. They were hand knit deliberately one-third too large, typically by a fisherman’s wife, although they could also be bought along with other supplies. Exceptional warmth was derived from the fisherman’s repeatedly wetting the woolen mittens in salt water, tossing them on the deck, tromping on them as he hauled traps, allowing them to marinate in fish gore, molding them until they fit his hands. As they dried, they shrank, which made the mittens superbly insulating, thick enough for winter work in Casco Bay. Heading out, he would wet them again and their wetness kept his hands dry. If not for one woman, Minnie Doughty, of Chebeague Island, who lost several of her six sons to the sea, Hansen believes this particular pattern would have been lost. But when Doughty died, her daughters kept the single remaining new, unshrunk pair as a keepsake. Another local knitter later measured the oversized mittens, counted stitches, found a loose end to determine the yarn’s thickness and reconstructed the instructions. [peter—see attached photocopies of this process…I found her writeup confusing, perhaps you will too? G]

Double-Rolled Mittens first came to Hansen’s attention when she exhibited her personal mitten collection at a heritage festival in Maine and another knitter observed there were no double-rolled mittens in the display. Later she learned how to knit them from a woman who was raised on a farm in New Brunswick where as a child she learned the technique from a neighbor. Says Hansen, “If you knit a pair you will be helping to revive a nearly vanished craft, like making Clovis knife blades or writing in hieroglyphs. They are special.”

There are tidbits throughout the book. At one time, most mittens in Maine had no ribbed cuffs. Instead, separate “wristers,” variously known as “pulse warmers,” “half-handers,” “half-mitts” or “fingerless gloves,” were slipped on before the mitten itself. Or one might wear them alone for work that required dexterity—delivering mail, repairing engines, or typing in a drafty office.

Above all, Hansen wants knitters to pick up their needles and try the wonderful folk patterns themselves. She updated instructions based on feedback she receives in workshops she conducts across the country. Photos and instructions are clear. Measurements are provided from a child’s small to adult extra-large. She notes which patterns are easy to follow, which are for experienced knitters. One section is devoted to double-knit mittens and matching caps for babies and small children. There’s also a resource list for the yarns used in the book.

——Janet Mendelsohn

Secondary Title Text

Best Traditional Mitten Patterns...