Pectoral fins from a mature right whale (left) and her fetus.

Pectoral fins from a mature right whale (left) and her fetus.

Stumpy was a North Atlantic right whale, so-named because she was missing part of one of her flukes, almost certainly due to a ship strike. In 1981, she was entered into a photo-identification catalogue kept by the New England Aquarium.

At work inside the right whale named “Stumpy”

At work inside the right whale named “Stumpy”

Stumpy lived a long and fruitful life, but she and a nearly full-term fetus inside her met with a tragic end when she was struck and killed by a large ship in 2004. Her skull had been fractured. She was a fully mature adult, at least 35 years old when she died. Her carcass and that of her baby were collected at Nags Head, North Carolina. Today, both skeletons are on display at the Nature Resource Center of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science in Raleigh, thanks to Maine whale expert Dan DenDanto.

Dan DenDanto: skeleton rearticulation specialist. DenDanto is a specialist in a distinctive skill: the rearticulation of large marine mammal skeletons. Over the past 20 years, he has gained national renown in the field. A resident of Seal Cove on Mount Desert Island, he is a research associate at Allied Whale (the marine mammal research group associated with College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor), and he is director of its North Atlantic Fin Whale Catalogue. He has been affiliated with such award-winning productions as the BBC’s Blue Planet series, I-Max’s Living Seas, and various Maine Public Broadcasting programs. He is a forensic analyst of the University of Maine Molecular Forensic Laboratory for Wildlife, utilizing DNA samples to investigate crimes against wildlife across the northeast U.S.

Dan DenDanto: skeleton rearticulation specialist. DenDanto is a specialist in a distinctive skill: the rearticulation of large marine mammal skeletons. Over the past 20 years, he has gained national renown in the field. A resident of Seal Cove on Mount Desert Island, he is a research associate at Allied Whale (the marine mammal research group associated with College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor), and he is director of its North Atlantic Fin Whale Catalogue. He has been affiliated with such award-winning productions as the BBC’s Blue Planet series, I-Max’s Living Seas, and various Maine Public Broadcasting programs. He is a forensic analyst of the University of Maine Molecular Forensic Laboratory for Wildlife, utilizing DNA samples to investigate crimes against wildlife across the northeast U.S.

Preparing whale bones is a large-scale endeavor. Here, a pressure washer is used to clean a mandible.

Preparing whale bones is a large-scale endeavor. Here, a pressure washer is used to clean a mandible.

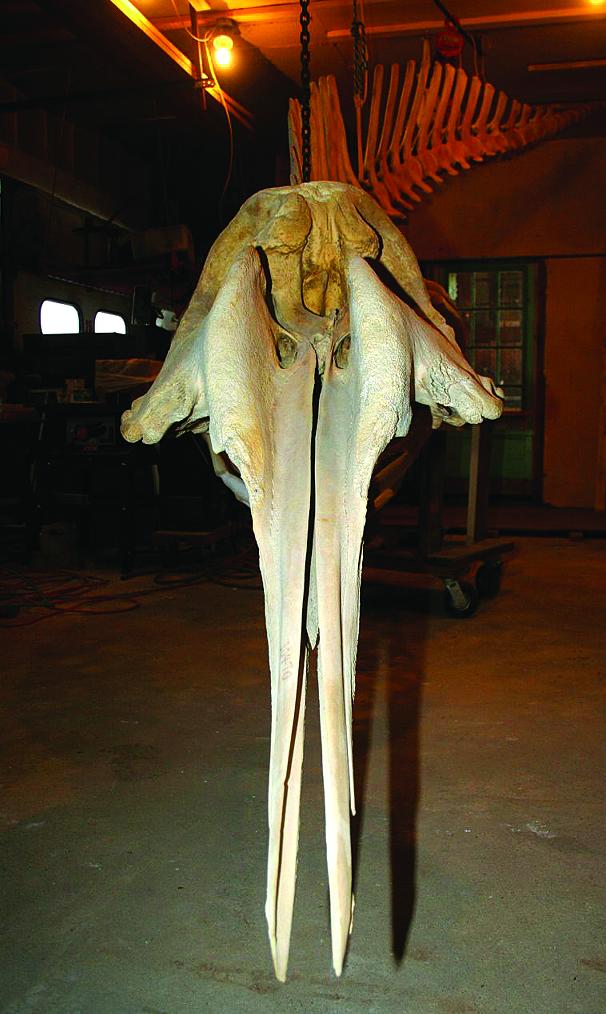

The beaked whale is aptly named.

The beaked whale is aptly named.Since 1993, DenDanto, through his business, Whales and Nails, has cleaned and rearticulated numerous skeletons. For the New Bedford Whaling Museum, he suspended the skeleton of a 48-foot right whale and that of her fetus, killed by a boat propeller, 25 feet in the air. For a museum on Nantucket Island, he created a dramatic installation with a 46-foot male sperm whale that died on a Nantucket beach; the whale, mouth open, is in a diving position. For the Seacoast Science Center in New Hampshire, he cleaned the carcass of a two-year-old humpback whale found floating off Massachusetts and reassembled the 800-pound skeleton. Cleaning involved towing the carcass to shore, sectioning it, and burying it in a landfill for a year.

Stumpy measured 52 feet long and was well along in her pregnancy when she was killed. For that exhibit, DenDanto placed the fetal skeleton inside the mother’s. He suspended Stumpy’s skull and the upper part of her skeleton by straps from the rafters of his workshop, then he and his assistants wove their way in and out of the ribcage, fitting the bones, which were 7 or 8 feet long, in an armature that held together the spine. He set up the final exhibit in the museum with a team of riggers, a forklift, winches, and hydraulic scaffolds.

The work is hands-on and physical, but also makes use of modern technology.

The work is hands-on and physical, but also makes use of modern technology.

“When you look at it,” DenDanto said, “there will be no mistaking that she was a pregnant mom. This is not just any North Atlantic right whale. These are important individuals to preserve. It’s the breeding females that are the most important. And a very high percentage of ship-killed animals are females.”

Assembly of the skeletons involves such factors as ensuring proper calibration between the bones and decisions regarding support and fastening materials.“It’s analogous to stringing beads,” DenDanto said of putting together vertebrae. “There’s a certain spacing that we’re aware of. We simulate cartilage between the bones of the spine, and we have control over that spacing. It’s wider toward the tail section, where the animals have more movement.”

Through discussions with other design and construction contractors responsible for the North Carolina museum’s overall exhibit, DenDanto decided on the configuration and orientation of the skeletons. The museum asked him not to repair the jagged bones where Stumpy’s skull was fractured, because the injury would become part of the story told by the exhibit.

DenDanto and his team also determined how wide to spread the lower rib cage to accommodate the fetus. The fetal skull had been lost at some point between the ship strike and collection, so the team used a mock skull as a reference point.

DenDanto with bones from a whale named Snow.

DenDanto with bones from a whale named Snow.

“I cannot express how marvelous the size of the fetus was,” he said. “I did a fetus for a right whale before, and it was only 12 feet. This one measures some 17½ feet.” Construction of the fetal skeleton posed challenges because the young bones were so lightweight. “Don’t breathe on them or they’ll disintegrate,” was the standing approach, he said. “On the other hand, the density and the weight of the mother’s bones represented the other extreme.”

The mother probably weighed 60,000 to 80,000 pounds when she died. She floated at sea until washing up on shore. “Literally, the fetus just pulverized inside of her for the day or two she floated around,” DenDanto said. “They described the fetus as being like a sock that contained loose bones.”

Many displays of whale skeletons use metal hoops to support the rib cage. For the Stumpy exhibit DenDanto opted for a more elegant, less visible series of epoxy-embedded pins. “So when you look at it, you will not see steel,” he said. “We want to see the whale, not what’s holding it up. We’ve taken the extra steps.”

DenDanto’s work sometimes involves skeletons of whales that were collected a long time ago. For example, he has worked on a 21-foot-long killer whale, its skull full of Tyrannosaurus-like teeth, and a 24-foot-long northern bottlenose whale that had been collected in the early 19th century off the Faroe Islands in the Norwegian Sea. The two perfect specimens had long been stashed in a dusty, cramped storage area at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

“The attic was like a scene from Indiana Jones,” DenDanto said. “There were ungulate skulls and horns just everywhere. It was a little weird, all these skulls looking at you.”

Handiwork from a bygone day could be seen in the way previous conservationists at Harvard had laid out the whales’ spines in unnaturally straight poses and used hand-poured wingnuts to help hold the structure together. DenDanto was commissioned to rearticulate the skeletons in dynamic postures for display in the cathedral-ceiling staircase of a university laboratory.

The main challenge involved removing the ancient armature without damaging the bones, particularly the brittle ridges of the vertebrae. DenDanto and his team carefully cleaned the bones, submerging them in a warm detergent bath to break up dark lipids that had stained the surface, then replaced the old mounts with inert materials. For hanging, they used as little cable as possible, so that people wouldn’t be aware of the architecture holding it together.

Sections of a whale's spine, which will be joined in the final installation.

Sections of a whale's spine, which will be joined in the final installation.

Most recently, DenDanto and his whale gang have been cleaning and repairing the bones of a humpback, a migratory baleen whale, collected in Gustavus, Alaska, the gateway to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The 46.5-foot-long whale will be the second-largest rearticulated humpback skeleton on display in the world. “The bones are absolutely massive,” DenDanto said.

The animal, named Snow by photo-identification researchers, was a regular visitor to Glacier Bay and had been observed regularly since 1975. She died two weeks after her last sighting by researchers, in 2001. Evidence indicates that Snow, feeding in Glacier Bay, was hit in the head by a large cruise ship, which then probably ran over the upper part of her body, shattering vertebrae. “The skull was absolutely devastated on the right side,” DenDanto said.

Like Stumpy, Snow was pregnant, but her fetus was tiny and will not be reassembled. Contacted by the National Park Service, DenDanto undertook a 4,000-mile road trip across the country to get the bones back to Maine.

DenDanto and his team have had to deal with a fair amount of damage to the skeleton. In addition to the skull injury, several of the vertebral column’s “spinous processes”—bone projections that go up toward the back and hold the muscles that control the tail fluke—were broken. Post-mortem damage included beach abrasion and years of being gnawed on and nested in by rodents. The Park Service asked DenDanto to repair the natural damage but preserve the cracks associated with the ship strike. DenDanto credits College of the Atlantic as an excellent resource for reference specimens when he has to craft prosthetics for vertebrae and skulls.

On a recent visit to the Whales and Nails workshop, DenDanto took me outside, where Snow’s skull was perched on stands. “See the level of damage here?” he said, pointing to portions of the jaw, called maxillae, that were mangled or missing. “And these are the telltale tooth marks of porcupines,” pointing to an inner portion of the skull. Snow’s lower jaws and some of her vertebrae were in another part of his shop, having recently been removed from their first round in a boiling tank.

“Some of the caudal vertebrae are quite dark,” he said, “because they still have the oils and grease. You can see there’s still a little tissue associated with the jawbone. That boils off pretty readily.”

Skull fragments were piled in one corner, ready to be threaded with slender rods and fixed back in place with epoxy. Missing bone will be replaced with epoxy putty, feathered in and painted. “It’s like making a prosthetic bone,” he said.

An upbeat kind of guy, DenDanto loves to talk about a life’s work that begins with the world’s largest mammals and carries him into conservation and education for everyone from adults with PhDs to little children fascinated by creatures of the sea.

“You have to do something that speaks to all of them,” he said. “There are welding and construction sciences here, and then there’s whale anatomy, which is traditional science. And then there’s art and sculpture. I think it’s all of that. This is my 13th or 14th large-whale professional articulation, and still, every one is different. Every one is a learning experience. And every time I’m asked to do one of these things, I just feel very fortunate.”

Laurie Schreiber, a freelance writer, lives in Bass Harbor.

For More Information

Whales and Nails

846 Tremont Road, Seal Cove, ME 04674

207-244-0029; www.whalesandnails.com

College of the Atlantic/Allied Whale

105 Eden Street Bar Harbor, ME 04609

207-288-5015

www.coa.edu/allied-whale-microsite.htm