When the sun rises to its highest point in the sky and shines fully on us, we are truly re-created, we become new beings.

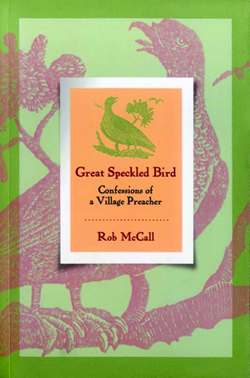

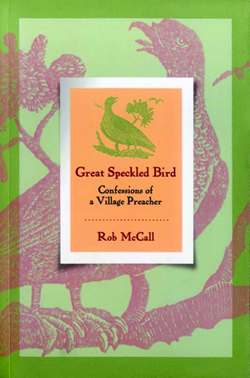

Rob McCall has taken several weeks off this summer and repaired to what he somewhat grandly calls the Awanadjo Almanack Cobscook Field Station, a one-room, log-frame camp on the farthest reaches of the Washington County coast. While he’s away we offer these excerpts from his latest book, Great Speckled Bird, published by the Pushcart Press in 2012. —The Editors

At Camp

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Thirty years ago when we built our camp on Cobscook Bay in Washington County, the easternmost in Maine, it seemed like wilderness, and really it was. People got lost in the woods there in those days. We made a small clearing and framed the cabin with the trees we cut down. The woods were close on every side, but over time we gradually cleared them away, and the woods seemed less wild.

One day, not a hundred feet from our cabin, we discovered a huge boulder left by the glacier, settled comfortably into the ground, draped with brilliant green moss on its north side, its top littered with the fallen needles of spruce and fir. For a long time we had not even known it was there. Its discovery was a revelation: A mighty rock within a weary land. Our delight was great with this touchstone, this anchor on the changing land. It was older than anything else we saw under the sky. Now we watch it from the cabin. We go out to sit upon it and feel its comforting inertia, its patience, its peace. We called it “Tunkashila” which is a Lakota word meaning “grandfather rock” or simply “God.”

Sometimes I imagine all the changes this grandfather rock has seen since the glaciers left it sitting 12,000 years ago on cold, bare bedrock scraped clean by the ice. Back then, the little brook next to the boulder ran with milky ice-melt, and the winds from the north blew bitter cold over the retreating glaciers. After a time, I imagine, lichens and mosses took hold on the surrounding bedrock, their decaying bodies building a thin topsoil to support the seeds of spruce, fir, and birch dropped by squirrels and jays as they slowly spread the forests northward from sub-glacial climes in what is now Massachusetts.

For thousands of years the first Americans hunted in the woods, and fished and clammed along the shores of Cobscook Bay, maybe camping by our boulder, using it as a landmark, a sitting place, and a windbreak for their fires, while spruce and fir sprouted, grew great, and fell to enrich the soil for their offspring. All the while, our boulder sat motionless as thousands of generations of mosses flourished and died upon it, thousands of generations of red squirrels shucked fir cones on it, and thousands of generations of ravens croaked and strutted and picked at the leavings, while the eagles soared above and the loons and seals called from the bay.

When the whites came—in this case the Irish some 240 years ago—they cleared the forests and ranged sheep, goats, and cattle over the land. I imagine a big Galloway bull scraping off his winter coat, or a goat scampering up on our boulder bathed in sun. After World War I, the farm was abandoned, and the fields grew up to woods again, wrapping our silent, abiding boulder in the cool dark of the forest for another 75 years, until the day we began cutting trees for our cabin and the sun shone upon it again, as it does today. “Change and decay in everything I see,” sings the old hymn, “O Thou who changes not, abide with me.”

At our camp, as we like to say, “the power never goes out.” That is because there is no electricity; also no phone or running water, and no road to the cabin door. Everything is carried in, or is there already. The power, however, is plentifully provided by the meeting of earth, air, fire, and water, and by the enveloping silence.

Fog and showers keep everything damp, but we manage to get a good lot of our work done. Fire does its work, too, as the woodstove dries our soggy things and the kerosene lights illuminate our reading at night. The profound silence sets your ears whispering for a day or so until it sinks in. You can hear the mandibles of a bald-faced hornet gathering wood fibers from the shingles. You can almost hear the slugs singing.

For about 25 years I mowed a couple of acres by hand with scythe and grass-whip. When I turned 60, I ruefully but gratefully accepted the gift of a roaring old power mower with big wheels that does the job in a third of the time. I try to hit the rocks at just the right angle, so that instead of dulling the blade, they sharpen it. It occurred to me that the American obsession with mowing is a way of clinging to the last vestiges of agriculture in an urbanized society. Just the way a sheep dog will herd chickens or cats or children if it has no sheep to herd, we zealously mow the grass as though we were making food for someone, even though we’re making nothing but noise and smoke.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Thirty years ago when we built our camp on Cobscook Bay in Washington County, the easternmost in Maine, it seemed like wilderness, and really it was. People got lost in the woods there in those days. We made a small clearing and framed the cabin with the trees we cut down. The woods were close on every side, but over time we gradually cleared them away, and the woods seemed less wild.

One day, not a hundred feet from our cabin, we discovered a huge boulder left by the glacier, settled comfortably into the ground, draped with brilliant green moss on its north side, its top littered with the fallen needles of spruce and fir. For a long time we had not even known it was there. Its discovery was a revelation: A mighty rock within a weary land. Our delight was great with this touchstone, this anchor on the changing land. It was older than anything else we saw under the sky. Now we watch it from the cabin. We go out to sit upon it and feel its comforting inertia, its patience, its peace. We called it “Tunkashila” which is a Lakota word meaning “grandfather rock” or simply “God.”

Sometimes I imagine all the changes this grandfather rock has seen since the glaciers left it sitting 12,000 years ago on cold, bare bedrock scraped clean by the ice. Back then, the little brook next to the boulder ran with milky ice-melt, and the winds from the north blew bitter cold over the retreating glaciers. After a time, I imagine, lichens and mosses took hold on the surrounding bedrock, their decaying bodies building a thin topsoil to support the seeds of spruce, fir, and birch dropped by squirrels and jays as they slowly spread the forests northward from sub-glacial climes in what is now Massachusetts.

For thousands of years the first Americans hunted in the woods, and fished and clammed along the shores of Cobscook Bay, maybe camping by our boulder, using it as a landmark, a sitting place, and a windbreak for their fires, while spruce and fir sprouted, grew great, and fell to enrich the soil for their offspring. All the while, our boulder sat motionless as thousands of generations of mosses flourished and died upon it, thousands of generations of red squirrels shucked fir cones on it, and thousands of generations of ravens croaked and strutted and picked at the leavings, while the eagles soared above and the loons and seals called from the bay.

When the whites came—in this case the Irish some 240 years ago—they cleared the forests and ranged sheep, goats, and cattle over the land. I imagine a big Galloway bull scraping off his winter coat, or a goat scampering up on our boulder bathed in sun. After World War I, the farm was abandoned, and the fields grew up to woods again, wrapping our silent, abiding boulder in the cool dark of the forest for another 75 years, until the day we began cutting trees for our cabin and the sun shone upon it again, as it does today. “Change and decay in everything I see,” sings the old hymn, “O Thou who changes not, abide with me.”

At our camp, as we like to say, “the power never goes out.” That is because there is no electricity; also no phone or running water, and no road to the cabin door. Everything is carried in, or is there already. The power, however, is plentifully provided by the meeting of earth, air, fire, and water, and by the enveloping silence.

Fog and showers keep everything damp, but we manage to get a good lot of our work done. Fire does its work, too, as the woodstove dries our soggy things and the kerosene lights illuminate our reading at night. The profound silence sets your ears whispering for a day or so until it sinks in. You can hear the mandibles of a bald-faced hornet gathering wood fibers from the shingles. You can almost hear the slugs singing.

For about 25 years I mowed a couple of acres by hand with scythe and grass-whip. When I turned 60, I ruefully but gratefully accepted the gift of a roaring old power mower with big wheels that does the job in a third of the time. I try to hit the rocks at just the right angle, so that instead of dulling the blade, they sharpen it. It occurred to me that the American obsession with mowing is a way of clinging to the last vestiges of agriculture in an urbanized society. Just the way a sheep dog will herd chickens or cats or children if it has no sheep to herd, we zealously mow the grass as though we were making food for someone, even though we’re making nothing but noise and smoke.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Rebecca is highly skilled at providing food and comfort under primitive camp conditions, and we have a blissful time. For amusement, I play the apple-box fiddle I made back in my orchard days. One damp morning I was playing “Sheebag Sheemore” to the fog, but somehow it just didn’t sound right. I shook the fiddle and heard a rattling inside. Opening it up, I shook out a huge mouse nest made of shredded leaves, feathers, pillow stuffing, and bits of black ribbon. This improved the sound of the fiddle, but only slightly.

I also found a yellow jacket nest in the ground in the very place where many summers ago I was stung for scything carelessly over it, which suggests that yellow jackets return to their favorite places, too. Chipmunks were more numerous than red squirrels that year for the first time in memory. Chippies make much better company: they are friendly and curious, and don’t act as though they own the place as the red squirrels do.

Several times I paddled out in the fog to go seal hunting on the bay. The trophy I sought was not pelt or meat, but a meeting with the harbor seals that loll on the ledges. I was not disappointed. One burly male scout with whiskers dripping followed me around and slapped the water to see if I would retreat. I stayed, enjoying the ethereal sensation of rising and falling in the foggy void out of sight of shore.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Rebecca is highly skilled at providing food and comfort under primitive camp conditions, and we have a blissful time. For amusement, I play the apple-box fiddle I made back in my orchard days. One damp morning I was playing “Sheebag Sheemore” to the fog, but somehow it just didn’t sound right. I shook the fiddle and heard a rattling inside. Opening it up, I shook out a huge mouse nest made of shredded leaves, feathers, pillow stuffing, and bits of black ribbon. This improved the sound of the fiddle, but only slightly.

I also found a yellow jacket nest in the ground in the very place where many summers ago I was stung for scything carelessly over it, which suggests that yellow jackets return to their favorite places, too. Chipmunks were more numerous than red squirrels that year for the first time in memory. Chippies make much better company: they are friendly and curious, and don’t act as though they own the place as the red squirrels do.

Several times I paddled out in the fog to go seal hunting on the bay. The trophy I sought was not pelt or meat, but a meeting with the harbor seals that loll on the ledges. I was not disappointed. One burly male scout with whiskers dripping followed me around and slapped the water to see if I would retreat. I stayed, enjoying the ethereal sensation of rising and falling in the foggy void out of sight of shore.

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, and fiddler, and pastor of the First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine UCC. This column derives from his weekly radio show on WERU, 89.9 FM, Blue Hill and 99.9 Bangor. The author’s latest book, Great Speckled Bird: Confessions of a Village Preacher (Pushcart Press), is available through your local bookstore. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Illustrations by Candice HutchisonAt our camp, as we like to say, “the power never goes out.” That is because there is no electricity; also no phone or running water, and no road to the cabin door.

In the fields the ox-eye daisies, orange and yellow hawkweed, yellow rattle, purple vetch, and blue-eyed grass offer all the colors of the rainbow to our wondering eyes. In the ditches and swamps the wild iris or “blue flag” flaunts its Buddhist blooms to soothe the fevered mind with mystic beauty. In the woods the new growth on spruce, fir, and tamarack is soft and pale green, dripping jewels in the fog.

In this land by the sea where the chipmunk stores seeds in a bird’s nest, the bears fertilize the blueberries, and the loons and the mourning doves call to each other, is it the stern law of tooth and claw, bloodshed and competition we see all around? Is it all struggle and the survival of the fittest? It is if we are seeing with only one eye. But if we are seeing with both eyes, it is the sweet law of nesting and seeding and feeding and mutuality. It is the survival of the kindest.

While joyfully engaged in the Sisyphean task of cutting brush on the high bank along the shore, I was treated to one of the most elemental natural events when the sound of thunder and the sight of strange, tortured clouds in the north gave me pause. An unfamiliar roar coming across the waters of the bay sent me scurrying up to the cabin just seconds before the heavens opened with the most horrendous hail storm I’ve ever seen.

Natural Healing

One of the marvels of the growing season is seen in the power of living things to heal. Trees sometimes lose a section of bark, scraped off by a piece of machinery or the falling of another tree against them, or where a branch is pruned off. During the growing season the careful observer will notice that under and around the edges of the wound, the living bark ever-so-slowly begins to expand over the bare, dead surface to conform to it, cover it and heal the wound. The “callous” that grows over the injury has the appearance of the bark of a young tree, even though the tree itself may be very old. The cambium layer of the bark is a plastic, flowing medium, the living plant flesh; forever young; forever trying to incorporate the wounded or broken places back into the whole body of the tree; forever trying to heal.

A similar phenomenon can be found on the surface of the ground. Perhaps a snow-plow last winter scraped the soil off an area leaving it bare and lifeless, or perhaps a larger area has been bulldozed for some narrow purpose. During the growing season this ground is gradually and naturally reseeded from living plants all around, and brought back to life. A plowed place, if left alone long enough, will repeat the primal history of the land around it by first going to grasses, brambles, and weeds, then to poplars and birches; until it finally becomes a part of the surrounding forest. The natural landscape tries to incorporate any anomaly, any disturbance or wound, back into itself.

The animal body heals in a similar way. A cut or scrape or wound on the flesh is slowly closed up and restored by the healing powers of life until it is made a part of the whole body again.

Why is this so? It could just as well have been the case that living things were given no power to heal and would continue to be barked and plowed and wounded over and over again and eventually helplessly succumb to the accumulation of injuries that come with life in a dynamic environment. But this is simply not the case. There is, in living things, an almost limitless power to heal.

The Spirit of life inhabits one great coherent body that brought all life into being out of a fiercely intense desire for it to be. We are not brought forth into a purely dog-eat-dog, law-of-tooth-and-claw, cold-and-cruel kind of place. We are not left alone and helpless against the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or the injuries of fate, or the wheels of destiny. We are given the gift of life that includes, yes, the possibility of hurt or injury; but also the marvelous power of healing, the power to re-incorporate every hurt, every wound, every injury—even death—back into the whole body which is life.

This power of healing is not necessary for life. The living world could surely exist without it. This power of healing is given because the world is a place of compassion not just compulsion, of love not just logistics—a place of feeling not just physics. We only need to see this power at work to make it work. We only need to get with it to get it.

Sun Worship

It is easy to see why sun-worship is still the world’s oldest religion. When the sun rises to its highest point in the sky and shines fully on us, we are truly re-created, we become new beings. The deep-down cold is driven from our bones by the summer sun, and we feel at home once again in a friendly world, as far removed from the cold, gray, grudging sun of mid-winter as Heaven is removed from Hell. No matter how hard we may try to remember the rich luxuries of summer during the cold of winter, no fading memory can come close to the actual living again of these fulsome days.

Now, even the daisies turn their bright faces to follow the sun as it moves across the sky, so devout is their worship and profound their affection for the Source of all Life and all Light. Small creatures like the numerous kinds of bees begin their lively motions at dawn and keep busy until dusk, when they retire again, plump-full and satisfied with their day’s work upon the glowing flowers from which they derive food, drink, medicine, materials for building, and all things needful for their simple and true, harmless and honest lives. See how every possible shape, color, and fragrance of the cosmos is embodied in the flowers, leaves, and branches of plants. See how every possible motion, motive, sense, and sound from the whole realm of Nature is so elegantly expressed by the insects, birds, and wild creatures.

We walk in a wholly other world these days, a world of mercy and healing. A holy host of blooming, buzzing, beaming beings blesses us with the kind ministrations of their actual, mortal love for life. We are redeemed to the depths of our ragged souls. We come all apart. We are knitted back together. We are made whole again. Gosh, it’s great.

Now, where’d I put the bug-dope?

Yr. mst. hmble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, and fiddler, and pastor of the First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine UCC. This column derives from his weekly radio show on WERU, 89.9 FM, Blue Hill and 99.9 Bangor. The author’s latest book, Great Speckled Bird: Confessions of a Village Preacher (Pushcart Press), is available through your local bookstore. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

Awanadjo Almanack

Secondary Title Text

Welcome to Blue Hill: the Town, the Bay, the Mountain

Sections