This photo of Charlie Gomes sitting in front of some of his half models was taken in 1962. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderI was very young when I first met Charlie Gomes in 1956; he was already an old man and his simple bearing belied his reputation as the finest builder of wooden boats on Casco Bay. My mother had tracked him down the previous summer after falling in love with one of his sailboats, which we had chartered for a few weeks in July. That boat, named Arenjay, was a 19' centerboard sloop, green with red trim, an open cockpit, and Marconi rig. During the 1940s and 1950s Gomes had built quite a few boats on the same lines and they had become known locally as the Small Point Class.

This photo of Charlie Gomes sitting in front of some of his half models was taken in 1962. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderI was very young when I first met Charlie Gomes in 1956; he was already an old man and his simple bearing belied his reputation as the finest builder of wooden boats on Casco Bay. My mother had tracked him down the previous summer after falling in love with one of his sailboats, which we had chartered for a few weeks in July. That boat, named Arenjay, was a 19' centerboard sloop, green with red trim, an open cockpit, and Marconi rig. During the 1940s and 1950s Gomes had built quite a few boats on the same lines and they had become known locally as the Small Point Class.

At the end of that summer my mother sought out Gomes and commissioned him to build us a boat exactly like Arenjay. During the winter she made several calls from Washington, D.C., to check on the boat’s progress. He assured her that it would be ready for us when we arrived. Finally, in June, after getting settled in at our cottage on Sheep Island, my parents loaded all the kids into the skiff and motored across the New Meadows River to check on our new sailboat at the Gomes yard in Sebasco. There were a number of boats moored in the cove in front of his boat shed, but none of them resembled Arenjay. We tied the skiff and climbed up to peek through a window, but there was no sign of our new boat. My mother started to get edgy.

Royal Tern was restored in 2011 and went back into the water for the first time in years. In this photo, her mast is stepped forward of the cockpit. Since then, the mast step has been moved a bit farther aft. Photo courtesy Peter Alexander

Royal Tern was restored in 2011 and went back into the water for the first time in years. In this photo, her mast is stepped forward of the cockpit. Since then, the mast step has been moved a bit farther aft. Photo courtesy Peter Alexander

We walked up the road to the house and found Gomes just coming out the kitchen door, adjusting his tweed cap as we approached. He was a small, wiry man, slightly bent with age. His face was deeply lined, and his eyes had a mischievous twinkle when he spoke. He was wearing a khaki-colored shirt and pants that bore traces of paint and glue. His hands looked huge, with broad fingertips and knotted knuckles. He greeted us respectfully. When my mother, masking her concern, asked him about our boat, he replied amiably that it was down in the cove and suggested we walk down together to see it. I was too young to fully understand what was happening, but I could sense my mother’s tension.

Royal Tern as she looked in 1956, soon after she was built. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderWhen we got to the pier Gomes pointed to a beautiful white sailboat, floating like a swan in the middle of the cove. “There she is, Elisabeth,” he said. My mother stood in silence for a moment. “But Charlie,” she responded, “that’s not the boat I ordered.” Even I could see that the boat in front of us was very different from the one we had rented the previous summer. It wasn’t green with red trim, but white with blue, and it was noticeably larger, both longer and wider. Gomes turned to my mother and said, “Elisabeth, I didn’t build you the boat you ordered. I built you the boat you should have!” My mother was speechless. Gomes took his skiff and towed the new boat back to the pier. Up close we could see even more differences: it was a keel boat with no centerboard, so the cockpit was much larger than Arenjay’s, and instead of a Marconi rig Gomes had outfitted our boat with an old-fashioned gaff-rigged mainsail.

Royal Tern as she looked in 1956, soon after she was built. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderWhen we got to the pier Gomes pointed to a beautiful white sailboat, floating like a swan in the middle of the cove. “There she is, Elisabeth,” he said. My mother stood in silence for a moment. “But Charlie,” she responded, “that’s not the boat I ordered.” Even I could see that the boat in front of us was very different from the one we had rented the previous summer. It wasn’t green with red trim, but white with blue, and it was noticeably larger, both longer and wider. Gomes turned to my mother and said, “Elisabeth, I didn’t build you the boat you ordered. I built you the boat you should have!” My mother was speechless. Gomes took his skiff and towed the new boat back to the pier. Up close we could see even more differences: it was a keel boat with no centerboard, so the cockpit was much larger than Arenjay’s, and instead of a Marconi rig Gomes had outfitted our boat with an old-fashioned gaff-rigged mainsail.

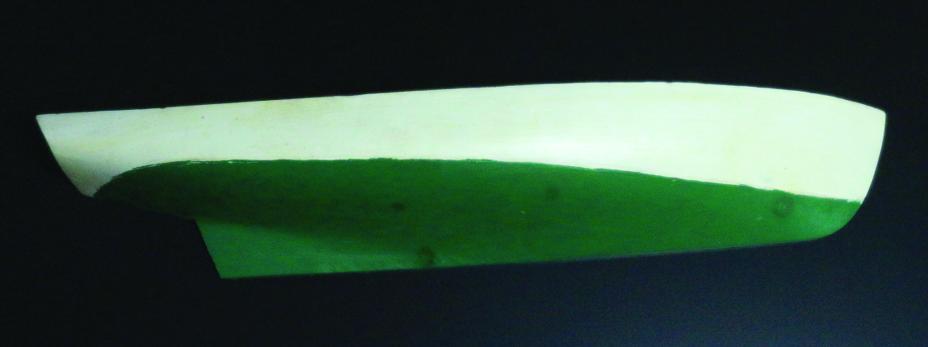

Builder Charlie Gomes carved models, like this one of the Small Point Class of boats, as part of his building process. He would then cut the model into sections and create full-sized wooden forms based on the resulting cross sections. This model is in the collection of the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderGomes explained that the extra length and beam and the large cockpit would much more comfortably and safely accommodate our family of seven. He also noted that a gaff-rigged sail was more to his liking for Casco Bay than a Marconi rig. It was useless to argue, and his gentle tone and absolute sincerity quickly disarmed my mother.

Builder Charlie Gomes carved models, like this one of the Small Point Class of boats, as part of his building process. He would then cut the model into sections and create full-sized wooden forms based on the resulting cross sections. This model is in the collection of the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderGomes explained that the extra length and beam and the large cockpit would much more comfortably and safely accommodate our family of seven. He also noted that a gaff-rigged sail was more to his liking for Casco Bay than a Marconi rig. It was useless to argue, and his gentle tone and absolute sincerity quickly disarmed my mother.

There were a few details that Gomes still had to attend to before we could sail the boat home. He started whittling a dozen wooden rollers that would ride on a piece of wire at the mast end of both the main and gaff booms. This device kept the booms from pulling away from the mast and allowed the sails to be raised or lowered without binding. After creating five or six rollers Gomes slipped and gave himself a nasty cut on the middle finger of his left hand. Blood went everywhere. I was taken aback, and my mother’s voice betrayed a level of emotion that we all shared. But Gomes was nonchalant. He calmly climbed up to his boat shed and came out a few minutes later with a big gauze bandage taped around the end of his finger. He reassured us that he was fine. “No boat of mine is complete until I’ve spilled some blood on it,” he said. He finished and installed the last of the rollers while his bandage gradually turned crimson.

Royal Tern had languished in a shed and was in an extreme state of disrepair before her 2011 restoration. Photo courtesy Peter Alexander

Royal Tern had languished in a shed and was in an extreme state of disrepair before her 2011 restoration. Photo courtesy Peter Alexander

I was deeply impressed with Gomes during this first hour of our acquaintance. That our boat, which my mother immediately named Royal Tern, was a product of both his artistry as a designer and his craftsmanship as a builder, was not lost on me. Before we left he took us into his shed to show us some other boats he was building. He wanted us to see the basic components that had gone into building Royal Tern, from design to completion. He picked up a wooden model from his workbench. Carved out of solid wood it was just half of a hull. Gomes explained that he carved models like this on a scale of one inch for every foot of the finished boat. When the half hull was shaped to his liking (he did everything by eye) he would cut it into sections every two or three inches and create full size wooden forms exactly replicating the shapes and proportions of the resulting cross-sections.

Gomes had only an eighth-grade education, had never studied naval architecture, and had no formal training in boatbuilding. His methods were self-taught, and his designs were the product of his artistic eye. But all of his boats—sailboats, skiffs, and lobsterboats alike—had exquisite lines. Whether standing at anchor or cutting through the sea, they exuded a sense of grace. He later told us that Royal Tern was his favorite boat, and the best sailboat he ever built.

The restoration, which was done by the author’s cousin Cyrus Cleary, took two years. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderBut like many wooden boats, Royal Tern deteriorated over the years. Initially, Gomes took care of her each winter and kept her in good condition. In about 1960, at my mother’s request, he added a small bowsprit and 600 pounds of lead ingots in her bilge to accommodate a larger suit of sails. Throughout the 1960s the boat was a fixture on the New Meadows River near Cundys Harbor.

The restoration, which was done by the author’s cousin Cyrus Cleary, took two years. Photo courtesy Peter AlexanderBut like many wooden boats, Royal Tern deteriorated over the years. Initially, Gomes took care of her each winter and kept her in good condition. In about 1960, at my mother’s request, he added a small bowsprit and 600 pounds of lead ingots in her bilge to accommodate a larger suit of sails. Throughout the 1960s the boat was a fixture on the New Meadows River near Cundys Harbor.

After my mother passed away in 1973, my father and a couple of my siblings sailed Royal Tern whenever they could get to Maine, but shorter vacation times dramatically cut into sailing time and gradually the boat fell into disrepair. In the late 1980s she spent a few years under a tree in Phippsburg, covered by a torn tarp that allowed leaves and rainwater to accumulate in the bilge. Finally, in 1989 my brother and I agreed that getting her back into sailing condition was beyond our combined financial and technical abilities, and we sold the boat for $1 to our cousin, Cyrus Cleary, with the intention that he would eventually restore it and let us sail her from time to time. (Cyrus is a master craftsman with a shop and boatyard on the Dingley Island Road near Cundys Harbor.)

Reduced to “project boat” status, Royal Tern’s restoration time line stretched out. With my family’s acquisition in 1996 of Melody, a Bristol 27 sloop, the imperative to get Royal Tern back in the water faded to a distant memory. But my aging father didn’t forget. From time to time he would ask about her and I would remind him that Cousin Cyrus was going to restore her “one of these days.” Finally, just after his 91st birthday in the fall of 2008, my father told me “I want her back!” A quick phone call to Cyrus to negotiate the price set things in motion, but Royal Tern was in really bad shape. Her keel, garboards, and most of her oak ribs were rotted, the keel bolts were rusted away, and her rudder, deck, chines, floorboards, and coamings were beyond repair. Further, the hull was so soft that she had settled out of plumb by several inches. Amazingly, however, most of the pine strip planking of her hull was intact, and her Sitka spruce spars were still usable.

The restoration took nearly two years to complete. We tried to retain as much as possible of Gomes’ original design, but we did make a few modest changes. We got rid of the bowsprit and the lead ingots in the bilge, opting instead to install a new oak keel 8" deeper than the original. Royal Tern had always suffered from a strong weather helm, which became worse over the years as the huge mainsail stretched. To remedy this we moved the mast step back about 12", added a larger jib, shortened the foot of the mainsail by several inches, and dramatically changed the angle of the gaff, drawing the peak of the main up and forward, quite a bit closer to the mast.

Cyrus suggested extending the coaming forward at an angle to meet on the foredeck in front of the mast instead of the original “square across the front of the cockpit” design. This mostly remedied an age-old problem of spray washing across the foredeck and into the cockpit in rough water. We also dropped the center section of the floorboards by about 6" to make the cockpit more comfortable, and installed a hinge on the tiller to make coming about easier on the knees. The only other significant change was the installation of modern snap cleats for the jib and main sheets, allowing for easy single-handed sailing.

A new suit of sails completed the restoration—or should I say “transformation”—of Royal Tern. After being out of the water for 20 years it took a couple of seasons for her to tighten up, but she is now an amazingly dry boat and sails beautifully in light to modest winds.

These days we keep Royal Tern in the water for most of the summer and she can often be seen sailing in the New Meadows between Small Point and The Basin. As of this writing my father, now 98, has been delighted to see photographs and videos of the restored boat. Cousin Cyrus has offered to trailer her down to DC this spring and launch her in the Potomac River if I can find a way to get my father to the water’s edge. We’re working on it.

Peter Alexander (also known as Peter Blachly) is a musician and writer living in Bath. This story is based on a chapter from his soon-to-be published memoir The Stone from Halfway Rock. Peter welcomes your correspondence at peter@peteralexander.us.