“The snowy trees were everywhere bent into the path like bows tautly strung, and you had only to shake them with your hand or foot, when they rose up and made way for you. Ever and anon, the wind shook down a shower from high trees.”

—From Thoreau’s journal, January 19, 1855

Dear Friends:

One good thing about having a bitter cold snap early in the winter is this: unless it gets down to 20 below and stays there for two weeks, anything the season can throw at us will look mild compared to what we have already been through; we’re hardened-off good and proper. Bitter cold is particularly hard for those who work outside or keep animals. Machinery gets cranky and may break or refuse to run; the animals must be fed and watered regardless of the weather. Chores that take an hour when it’s milder may take two or three when it is so cold. But we learn from it and next time it happens, maybe we’ll be better able to handle it.

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Field and forest report, January

Despite the cold, some outdoor work is best done in winter, particularly orchard work and woods work. In the orchard, it’s pruning time because the sap is down in the roots and less likely to freeze and damage the living bark around pruning cuts, and there is less chance of infection since disease organisms are inactive in the cold. In the woods, it’s time for cutting and skidding out logs for lumber or firewood. Winter-cut wood needs less time to season since the sap is down, and skidding is much easier over frozen ground.

So, snow or no snow, pruning is under way in apple orchards across New England. From figs and olives in the ancient East to apples and pears in the modern West, gathering food from trees is one of the oldest kinds of agriculture. The Tree of Life is one of the most abiding mythical motifs of humankind, appearing in nearly all cultures. Being entrusted with the care of one apple tree, or 100, is a gateway to a world of wonder.

There is nothing to match the feeling of standing in the top of an old-fashioned standard Wolf River apple tree on a mild winter day with the smell of sweet sawdust and the sound of seagulls circling under a blue sky with sunlight reflecting off the snow, setting the soaring birds aglow. It is a wonder and a privilege to care for these large living things. It takes patience and a long view to prune a tree well. Everything the pruner does affects the future life and health of the tree. Ignorance or carelessness or haste can do harm, and yet it will be several months, or even years, before we can know how well we have done. And so it is with the whole Tree of Life.

Natural events

On the snow-covered ground, visitors leave their marks. Here are the tracks of a crow circling a bit of scrap we tossed out on the ground; approaching, retreating, circling, and approaching again. And there is the brush of his pinions etched in the snow where the tracks end and the wind raised him high with his prize. There are the tracks of deer who waited until deep dusk to wander shyly out of woods and into the orchard to forage for frozen fallen apples, pulling away the frosted grass to find the sweet treasure beneath.

Illustration by Candice HutchisonCritter report

Illustration by Candice HutchisonCritter report

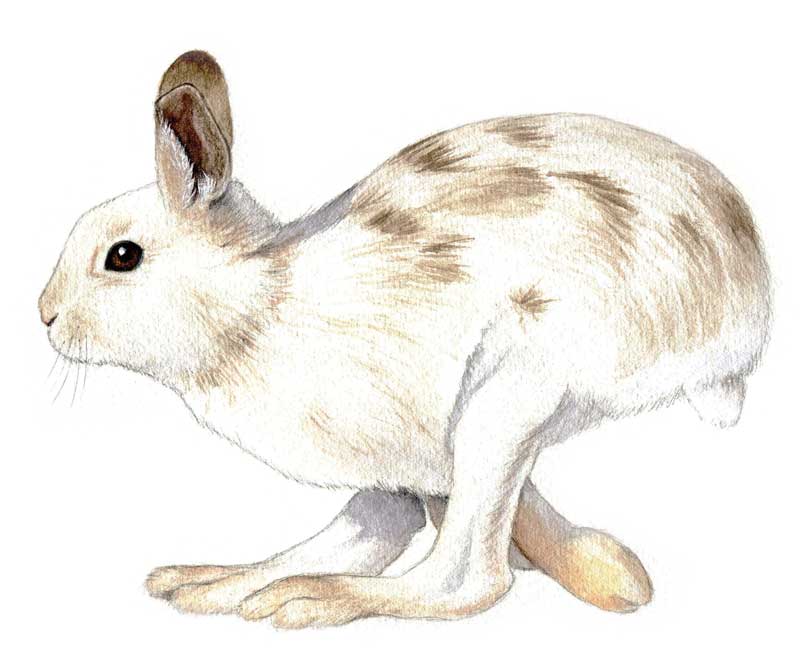

River otters (Lontra Canadensis) are great sliders down snowy slopes or across icy ponds, but for getting around in the snow the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) knows no equal. The snowshoe hare has enormous hind feet covered with fur to protect it from cold and to help it walk on snow. These hares turn white in winter for protection. They are the prey of many carnivores, including man, and are the preferred food of the Canada lynx (Lynx Canadensis) whose population rises and falls with that of the showshoe hare.

The hare leaves a distinctive and unmistakable track in the snow, looking like two large exclamation points. You can’t miss them.

Natural events, February

Even though studies consistently show that at least one third of Americans don’t get enough sleep, sleep is natural, especially in the winter. Hibernation is not just for the bears. With the weather forbidding, the ground frozen and the nights long, what better than to catch up on all that sleep we lost last summer, or last year, or back in our 20s and 30s when sleeping was optional, but partying was not. Now that I’m older, hibernation done right can be an extreme luxury. After dinner I’ll sit by the stove and get drowsy over a theology text or a history of the Transcendentalists and maybe even a cup of chamomile tea. The book works as fast as the tea—faster, actually. Then, when my eyes start to close I’ll hoist myself up one more time, brush my teeth, give my honey a kiss, and pad off to our huge bed in the cold bedroom overlooking the Benjamin River just in time to miss the State of the Union address. One more page of Emerson and Thoreau with my skull on the pillow and my bones under the quilt, and, brothers and sisters, I’m gone where good bears go.

Bears have it easy, though, you know. All they have to do is fatten up on free wild blueberries and beechnuts, find a warm den for the winter, and let Nature take her sweet course. We have it a little harder. For one thing, some humans are morning people and some are night people and they often find themselves under the same snowy roof. For another thing, bears don’t have to go to work or to school all through the long winter.

Anyone who has tried to rouse a sleeping teenager for four years of early morning calculus or civics or European History will see the sublime wisdom of starting classes at a saner hour as many secondary schools now do. Question: How many promising careers have been nipped in the bud because of a naturally somnolent adolescent brain that didn’t start working effectively until 10 o’clock, even though the body appeared reasonably operational by 7? Answer: Probably millions.

Wild speculation

I suspect the experts may one day find ancient evolutionary reasons for all this. Survival once dictated that some stalwart souls stay awake at night to tend the fires and fight off marauding wolverines or barbarians, saving a peaceful, tribal village from destruction. What’s more, the young have always wanted to do their courting at night. No courting, no babies. No more babies, no more us. See? This is why the young stay up late: It makes survival sense. Students, show this to your parents and teachers, who may not yet be too old to remember. And if that doesn’t work, try reading this Almanack in bed. It could help put you to sleep.

Field and forest report

Yes, the bears are slumbering soundly in their dens for the duration, and the chipmunks in the woodpile, and the frogs in the mud of the pond, but on a milder night the skunks may rouse themselves and rustle about in the dark; and the porcupines may rise to greet the dawn with reverence. During the day, cedar waxwings are flocking to feed on last year’s old apples, rose hips and viburnum berries. At night the birds retire into the treetops and the thick puckerbrush to hunker down, slumber lightly and knit up the raveled sleeve of winter care. Sleep, sleep soundly, one and all.

Saltwater report

Down on the mudflats herring gulls and black-backs poke around in the rockweed looking for clams, mussels, periwinkles, carnivorous snails, and whelks before the ice creeps back in, as it soon will when the thaw is over. We’re all getting into the rhythm of this together, all our relatives.

Natural events

During these days while the world is all gray, white, and black like a chickadee’s back, or with a touch of blue like a blue jay’s wing, and while the glorious palette of summer is a faded memory, what should appear in the mail but brightly-colored seed catalogs, their pages shimmering with all the shades of the rainbow: the smiling faces of flowers and the plump bodies of pumpkins, cabbages, beans, beets, berries, and rutabagas. Like travel brochures from another country, the seed catalogs remind us what our own local gardens, farms and fields will look like when all the colors return to us again, and we return to them in the country of summer.

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Martin Luther, 1483-1546:

“Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple trees.”

That’s the Almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Yr. mst. humble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall

Rob McCall splits his time between way downeast on Moose Island and Brooklin, Maine. This almanack is excerpted from his weekly radio show, which can be heard on WERU FM (89.9 in Blue Hill, 99.9 in Bangor) and streamed live via www.weru.org. Tell Rob what you went out and saw for yourself at awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com.