All artwork photography courtesy the artist

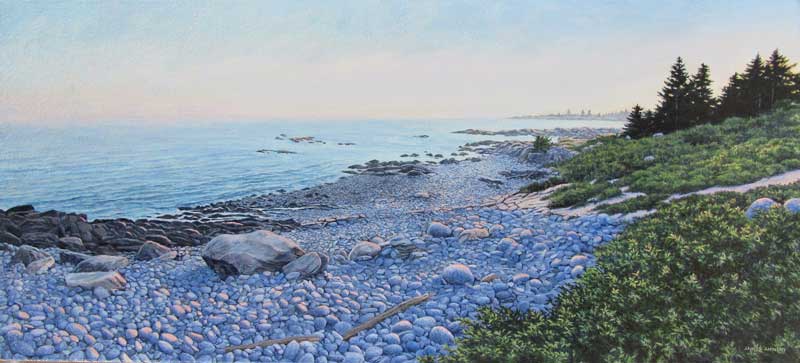

Anthony found it mesmerizing to paint the stones on a Schoodic beach, one by one. Schoodic Point, acrylic on linen, 2019, 18 by 40 inches.

Anthony found it mesmerizing to paint the stones on a Schoodic beach, one by one. Schoodic Point, acrylic on linen, 2019, 18 by 40 inches.

“Like pushing a rock up hill,” is how Janice Anthony describes the process of starting a new painting. “It’s slow—you have no momentum,” she explained. In the beginning she is easily lured away, by a cup of tea or some task or distraction: gardening, which she loves, or a visit to Facebook where she might check in with the Arthurian Illustration group or one of many plant alliances (she knows her flora). But once the painting is under way, Anthony gains focus and determination.

Working from sketches and photographs, she begins to block in the image, developing composites and different elements of the motif. She tends to start on the hardest part of the painting first, as she finds the most complicated passages the most interesting.

Janice Anthony, in her studio, blocks in the composition for the painting Outlook, Schoodic Point. Photo by Carl Little

Janice Anthony, in her studio, blocks in the composition for the painting Outlook, Schoodic Point. Photo by Carl Little

She does not make things easy for herself. For example, on several occasions she has painted a cobble beach near the Ravens Nest pull-off on the Schoodic Point road in Winter Harbor. Where another painter might find rendering the innumerable cobbles monotonous, she finds the repetition “kind of mesmerizing”: shadows and light, over and over.

Anthony is renowned for the intricacy of her paintings; she has been featured in publications and national exhibitions focused on realism. Her work is not the every-blade-of-grass verisimilitude of Andrew Wyeth, but more akin to, say, the Pre-Raphaelites, whose painstaking detail she admires. Her subject matter is almost entirely landscape-oriented—no Ophelia floating in a stream—but there’s a quality that sometimes borders on the surreal.

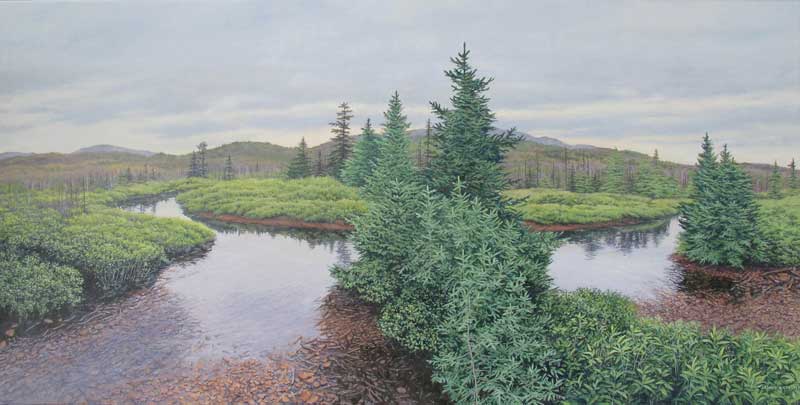

The Parc national des Grands-Jardins in Quebec is among Anthony’s favorite places to paint. “It’s all reindeer moss and dwarf spruce—just beautiful.” Disappearing Stream, Les Grands-Jardins, acrylic on linen, 2017, 20 by 40 inches

The Parc national des Grands-Jardins in Quebec is among Anthony’s favorite places to paint. “It’s all reindeer moss and dwarf spruce—just beautiful.” Disappearing Stream, Les Grands-Jardins, acrylic on linen, 2017, 20 by 40 inches

Some of Anthony’s earliest work, from the 1990s, featured trimmed hedge mazes with small fires disturbing otherwise idyllic imaginary settings. She eventually moved on from these enigmatic scenes, but not entirely. Encouraged by Rosemarie Frick, of the Frick Gallery in Belfast, she sought out “Maine mysteries,” places that had a similar otherworldly quality, like Devils Head in St. Albans, an archaic well stone on Mount Waldo, or a standing stone on Isle au Haut.

Tom Crotty, another renowned Maine art dealer who also was an artist known for meticulous realism, saw Anthony’s acrylics at Frick Gallery and signed her on to his Portland gallery, Frost Gully. While he had found her maze pieces “melodramatic,” her new work struck a chord. When Crotty passed away in 2015, Anthony mourned the loss of a friend, a curmudgeon “with the heart of a marshmallow.”

Over the years, Anthony has painted a variety of Maine landscapes: Vinalhaven, Sagadahoc Bay, Katahdin Stream Falls, Gulf Hagas, Cobscook Bay, and Moosehead Lake, to name a few. “You have to be looking for something that will talk to you when you see it, so you have to get off into odd places,” she said. Anthony sometimes finds subjects closer to her home in Jackson, including Belfast’s Passagassawakeag River. Newspaper editor Jay Davis taught her the proper pronunciation—sounds like Puh-sag-gus-uh-WAH-keg; “I’ve painted that river at least five times so I have to say it right,” she said.

In Outlook, Schoodic Point, Anthony offers a prospect of the ocean and granite ledges framed by spruce. Acrylic on linen, 2020, 24 by 31 inches

In Outlook, Schoodic Point, Anthony offers a prospect of the ocean and granite ledges framed by spruce. Acrylic on linen, 2020, 24 by 31 inches

Anthony’s painting territory stretches to Kent, England, where a sister lives, and Canada, where she and her husband, David Greeley, often travel. She is especially fond of the Parc national des Grands-Jardins, a preserve in Quebec where the southernmost incidence of tundra occurs. “It’s all reindeer moss and dwarf spruce—just beautiful.”

Anthony is one of the foremost painters of Maine winter, which she embraces, “maybe,” she explained, “because the land is covered, life is hidden.” She also is an expert in conveying atmosphere, be it fog on lily-padded water, overcast skies, or the glowing light of autumn. Like Joel Babb, her late mentor Crotty, and a handful of other painters, she practices an exquisite realism that opens up new worlds to the viewer. At the same time, there is an intimacy to her vision of the natural world that invites the viewer to enter in.

Anthony grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, as did her husband—they knew each other through the Unitarian Church. They started going out while at Boston University where Anthony, who was an English major, dreamed of becoming a novelist.

The couple eventually moved to Maine, to the Farmington area. Anthony taught junior high in Mechanic Falls. It was a short-lived stint—she didn’t have the “right temperament” to maintain order. They moved to Canton for a number of years, raising three boys. Greeley worked in the woods while Anthony substitute-taught and painted.

“I’d always painted since I was a kid,” she recalled, and over time canvases replaced writing notebooks. She was largely self-taught; “I just kept going and going, making mistakes and learning from them.” She worked for a time at a frame shop in Waterville where she met fellow painters and became a part of the art community. After a time, she quit framing to paint full-time.

Full-time, that is, with many other significant pursuits mixed in: The couple’s 180-acre property in Jackson includes a farm where they raise brood cows and harvest hay. Anthony has also created extensive woodland gardens, which have been shared with the community through the annual Belfast Garden Club’s Open Garden Day. The plantings, often started in her greenhouse, range from perennials to out-of-the-ordinary trees, like sequoia.

A quiet pond in morning mist along Route 7 in Jackson caught Anthony’s eye. “You have to be looking for something that will talk to you when you see it.” Morning Fog, acrylic on linen, 2019, 24 by 24 inches

A quiet pond in morning mist along Route 7 in Jackson caught Anthony’s eye. “You have to be looking for something that will talk to you when you see it.” Morning Fog, acrylic on linen, 2019, 24 by 24 inches

In the past two years the gardening part of her life has had an unfortunate side-effect: two bouts of Lyme disease, the most recent this past spring in the midst of the pandemic. Anthony appreciated the irony of “practicing social distancing for months, only to be attacked in my own garden,” she wrote in an e-mail in June. Thankfully, she recognized the symptoms much earlier this time and was well on her way to recovery by early summer.

Anthony and Greeley love their spot in Jackson. Some elevation—about 900 feet—provides “serious views,” including distant prospects of Blue Hill and Acadia. They’ve been there about 40 years now.

The landscape has changed in that time. Anthony worries about the various blights that have impacted the forests and the lack of action as the current administration backs away from environmental protection. She supports the Natural Resources Council of Maine, Earth Justice, and other organizations focused on stewardship. “Some of us want to find the otherness of the natural world,” she said, “but others just want to run a pipeline through it.”

Anthony finds comfort in the land and finds retreat in her cozy studio off the kitchen. “That’s where I wanted it when we built the house,” she said, “so I didn’t have to trudge through the snow.” There, mixing her favorite greens and purples, she takes up her brush to bring us to those special places that are of this world—and apart from it, too.

Carl Little’s essay “John Marin’s Islands” appears in the 2020 edition of The Island Journal. He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

Janice Anthony is represented by Courthouse Gallery Fine Art in Ellsworth and Gleason Fine Art in Boothbay Harbor. You can see more of her work at www.janiceanthony.com.