The sawdust shed, perched on its spindly pilings, overlooks Lubec Narrow and Campobello. Photo by Greg Rössel

The sawdust shed, perched on its spindly pilings, overlooks Lubec Narrow and Campobello. Photo by Greg Rössel

Lubec is known for spectacular scenery and dramatic fog, and both were present in abundance one morning in August at the McCurdy Smokehouse Museum overlooking Campobello Island. Still smelling of smoke and fish, the place contains artifacts, traditional tools and implements, hands-on demonstrations, and photos. The museum consists of four cedar-shingled buildings sitting atop pilings that extend into the Lubec Narrows. A fifth, the salt/pickling shed was lost in 2018 when a winter blizzard storm surge combined with a high tide floated it free of its weathered pilings; it washed ashore across the Canadian border on Campobello and briefly set off a minor international incident.

At one time Lubec bristled with commercial piers—smokehouses, sardine canneries, lumber and coal businesses, ship chandleries, boatbuilding yards and steam ship landings, keeping hundreds of people employed. In 1865, thirty herring smokehouses operated there. A former owner of the family business, John McCurdy, a spry 90 years of age, remembers when there were still about eight smokehouses and another six canneries in town. By the 1990s, the McCurdy smokehouse complex was the last of the traditional operations—sporting a warehouse on shore, and on an L-shaped wharf that ran out into the Narrows, two smokehouses, a sawdust shed, a boning and box assembly shed, and far out on the wharf, the pickling/brining shed.

In today’s parlance, the business of smoking herring could be called artisanal. Indeed, it varied little from that described in the classic 1887 government publication, Goode’s “The Fisheries and Fishery Industry of the United States.” The quality of the product entirely depended on the skills and experience of the operator to gauge the progress of the process by closely monitoring the effects of weather, temperature, sound, color, and even feel of the fish.

The smoking of herring was a seasonal business dependent on when the fish appeared in the weirs and the nets of purse seiners off Lubec, Eastport, the coast to Cutler, Gran Manan, and into New Brunswick.

The south smokehouse has ridgeline smoke vents and many air circulation windows. Photo by Greg Rössel

The south smokehouse has ridgeline smoke vents and many air circulation windows. Photo by Greg Rössel

John McCurdy recalls that the factory was closed during the winter for maintenance, and would start back up in May or June with the first run of fish from Shediac, New Brunswick. His father would bring in packed 10-wheelers and back them out on the precarious pier—reinforced with heavy planks—to the pickling shed. After his father died, John had everything delivered by American and Canadian boats, not trucks.

The many-stepped process of smoking the herring began with sluicing—pumping the fish up from the boat holds to the brining building through the wooden sluices and into the pickling tanks. The pumps could move a hogshead (17½ bushels – 1,225 pounds) of fish a minute. The crew had to work fast due to the tide (24 feet).

At the brining shed the silvery fish were salted in tanks to 60 percent salinity. The mixture was stirred with a spudge—a curious wooden hoe-like tool. It took five days to pickle the fish and drain the blood off. John McCurdy noted, “The accurate but unscientific method to determine if the fish had been pickled was to grab the fish and tug at the tail. If the tail tore, they had enough brining.”

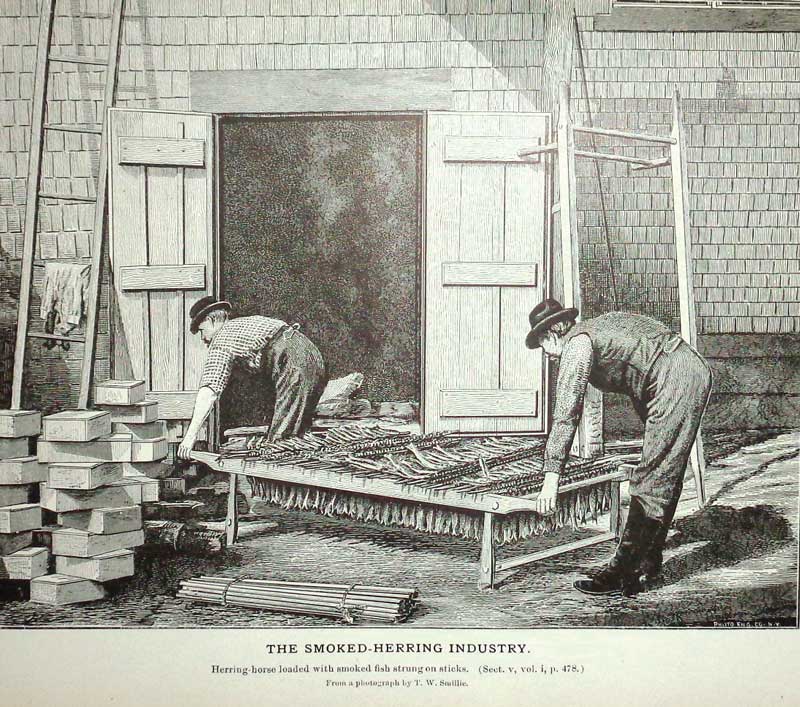

After brining, the fish were taken out of the tanks in buckets and dumped onto worktables where workers would lance or string them up (like laundry on a line) onto long-pointed dowel-like sticks by passing the stick through the fish’s gills and out through its mouth. Once loaded, the sticks were hung on a four-legged rack known as a herring horse or cart. For years workers carried the racks by hand; in a nod to modernity, wheels were added later in the 20th century.

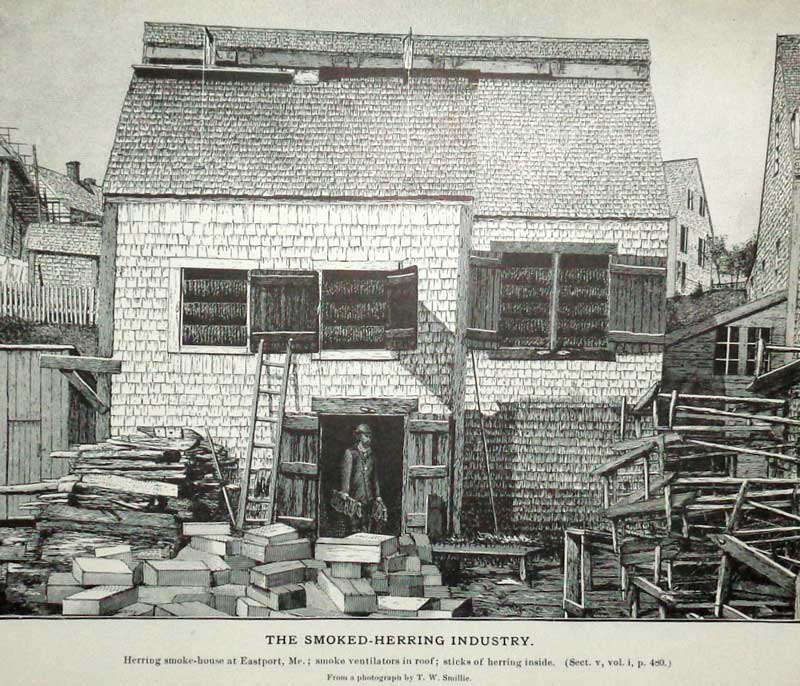

The smoking technology at McCurdy’s was nearly identical to these plates from George Brown Goode’s 1887 publication The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Top: The smokehouse fully loaded with racked herring with the vent doors open. Firewood, packing boxes and “horses” are stacked outside. Bottom: The herring are impaled on long dowel-like sticks and hung on the herring rack to be carried into the smokehouse. Images from The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, collection of Penobscot Marine Museum

The smoking technology at McCurdy’s was nearly identical to these plates from George Brown Goode’s 1887 publication The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Top: The smokehouse fully loaded with racked herring with the vent doors open. Firewood, packing boxes and “horses” are stacked outside. Bottom: The herring are impaled on long dowel-like sticks and hung on the herring rack to be carried into the smokehouse. Images from The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, collection of Penobscot Marine Museum

The racks were wheeled out onto the wharf where the sun and wind would dry them for a few hours. They had to be watched; any sign of rain, and they had to be taken under cover—experience once again told the workers how long to let them dry. Then, the strung herring were rolled to the lower “bay” to be hung on rails in the smokehouse.

A foot of gravel on the deck protected the smokehouse from catching fire—up to 30 fires inside were fueled by spruce, fir, sawdust, and cut wood and watched 24/7 by a fire tender. “Windows” or vents in the house could be adjusted for draft and air circulation.

Initially, the herring-laden sticks were hung on the lower level closest to the fires while the fish dried until the gills hardened. At that point the fires were allowed to die down and the sticks were “handed up” in groups to the top, while new sticks loaded with fish were hung below, and the fires were restarted. This process continued until the building was full. As the fish nearest the top were judged sufficiently cured, they were removed and taken to the skinning shed. As McCurdy explained, “The fish needed to be stiff; so much so that they would ‘rattle’. If they did not, they would be put back up in the smokehouse. It took about two months of smoking to get it right.”

To skin the fish, workers would “Snip the heads off with scissors, take out the innards (gutting and deboning), strip the skin off and split the herring in half lengthwise,” McCurdy explained. The fish were then ready for boxing, weighing, and shipping.

“All the wood for the boxes came from Canada. No Maine mills were interested in milling it for us,” he said. “The salt and most of the fish came from Canada as well. Boxes were assembled right on site. The box wood had to be dry as it would affect the weight of the finished product. The boxed fish were strapped in bundles of four. The fish was packed in both wooden boxes and in cardboard. The wood was best.”

The finished product was stored in a cooler and shipped as far as Chicago and the Carolinas. And the smoked herring enjoyed strong niche popularity even in a time when refrigeration and modern highways ensured fresh fish could be delivered faster. Unfortunately, one customer was not a fan of this artisanal product: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

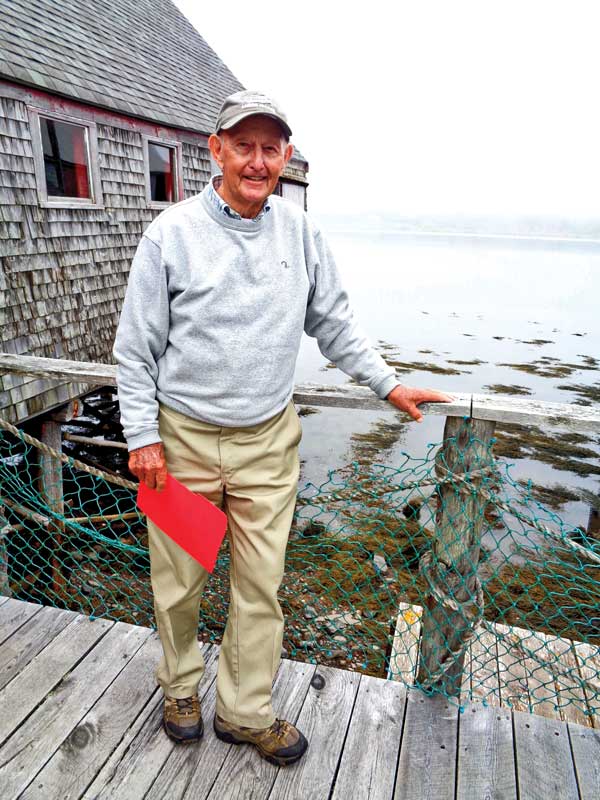

John McCurdy stands at the entrance to the museum. Before they collapsed, the wharf and the north smokehouse and brining shed extended behind him out into the Narrows. Photo by Greg RösselJohn McCurdy’s run in with the FDA began in 1990. The agency, citing a case in which three deaths from botulism were linked to smoked freshwater whitefish and a policy that fish be gutted before salting and smoking, demanded that the factory purchase a $75,000 machine. Thirty years later, John McCurdy still bristles at the FDA’s “better safe than sorry” action. The company only had $250,000 in annual revenue at the time; and besides, he said, “the fish would have to be eviscerated as a first step right off the boat rather than the last step. An impossible task—we’d never be able to do it (using the existing process).” McCurdy argued that botulism spores have never been found in Atlantic sea herring; and if there had been, the added salt would have killed and any spores. In an interview at the time with the Wall Street Journal, McCurdy argued that his company had produced three million pounds of herring without a single report of food poisoning. FDA inspectors had found nothing amiss in their yearly tests of his fish, he added. Nevertheless, in 1991 John McCurdy closed the doors to his smokehouse, laying off all 22 workers and bringing an end to a century-old enterprise.

John McCurdy stands at the entrance to the museum. Before they collapsed, the wharf and the north smokehouse and brining shed extended behind him out into the Narrows. Photo by Greg RösselJohn McCurdy’s run in with the FDA began in 1990. The agency, citing a case in which three deaths from botulism were linked to smoked freshwater whitefish and a policy that fish be gutted before salting and smoking, demanded that the factory purchase a $75,000 machine. Thirty years later, John McCurdy still bristles at the FDA’s “better safe than sorry” action. The company only had $250,000 in annual revenue at the time; and besides, he said, “the fish would have to be eviscerated as a first step right off the boat rather than the last step. An impossible task—we’d never be able to do it (using the existing process).” McCurdy argued that botulism spores have never been found in Atlantic sea herring; and if there had been, the added salt would have killed and any spores. In an interview at the time with the Wall Street Journal, McCurdy argued that his company had produced three million pounds of herring without a single report of food poisoning. FDA inspectors had found nothing amiss in their yearly tests of his fish, he added. Nevertheless, in 1991 John McCurdy closed the doors to his smokehouse, laying off all 22 workers and bringing an end to a century-old enterprise.

The factory was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1993. In accepting the nomination, the National Park Service noted the property was the “most intact—if not the only one—left in Maine. Furthermore, at the time of its closing in 1991, the McCurdy Smokehouse is said to have been the only commercial plant of its type in the United States.”

Recognizing the fact that the endangered representative of rural working waterfronts needed a champion, local residents founded Lubec Landmarks, Inc. as a nonprofit in 1996. The aim of the non-profit organization was preserving the history of the region’s sardine and herring industry of the region. The skinning and boxing/packing sheds now house artifacts and displays. Nearby, the Mulholland Market, from where the prepared fish was once shipped all over the U.S. as well as to Canada and the Caribbean, now serves as a gallery and gift shop. The museum also employs former employees of the smokehouse who explain and demonstrate some of the processes of the smokehouse industry.

All that said, there are literal clouds on the horizon: winter nor’easters and summer hurricanes. Maintenance is a challenge for any commercial traditional waterfront structure, especially factory buildings like these with their barn-like windage and the forest of stilt-like pilings that are constantly exposed to extremes of tide. The complex is relatively open to the elements, and weather has taken its toll. The aforementioned brining house was lost in 2018, and the north smokehouse was taken by a storm in 1997. Pieces of the roof on the remaining smokehouse are missing, and then there are those pilings. Repairs are needed soon and that takes money—a commodity in short supply in eastern Washington County.

For more than 100 years, this region was considered by many to be the herring capital of the world. These slouching buildings on Water Street are remnants of an industry that once powered small towns throughout Eastern Maine. Places like this are important for understanding the heritage of Maine. After all, if we don’t know where we have been, how will we know where we are going.

Greg Rössel lives in Troy and is a boatbuilder, instructor at the WoodenBoat School and its “Mastering Skill’s” video series, author, and host of “A World Of Music” on WERU FM.