The stately house built by sea captain George McManus in 1858 has stood the test of time and looks today much as it did when he built it. Photograph by David J. Clough

The stately house built by sea captain George McManus in 1858 has stood the test of time and looks today much as it did when he built it. Photograph by David J. Clough

From Kittery to Calais, Maine’s coastal towns and cities are graced with 19th-century homes built with the wealth of a vibrant maritime economy. Employing talented carpenters and masons, the state’s prosperous shipbuilders, vessel owners, and sea captains built stately homes that line the streets of Kennebunk, Bath, Belfast, and Searsport. In Brunswick, one of the most notable is the Captain George W. McManus House of 1858.

Captain George W. McManus. Image courtesy Pejepscot History CenterBorn in Brunswick on May 8, 1819, George McManus was one of the six children of Robert McManus’s marriage to Eleanor Crosby. (Robert’s previous marriage to Eleanor Coombs had produced seven children.) Of George’s older brothers, Richard, Nathaniel, Robert, and Asa became sea captains. At the age of 13, George went to sea with his brother Robert and compensated for his lack of a formal education by his love for reading. From then on, he began to amass a large library and a wide knowledge of the authors of the period.

Captain George W. McManus. Image courtesy Pejepscot History CenterBorn in Brunswick on May 8, 1819, George McManus was one of the six children of Robert McManus’s marriage to Eleanor Crosby. (Robert’s previous marriage to Eleanor Coombs had produced seven children.) Of George’s older brothers, Richard, Nathaniel, Robert, and Asa became sea captains. At the age of 13, George went to sea with his brother Robert and compensated for his lack of a formal education by his love for reading. From then on, he began to amass a large library and a wide knowledge of the authors of the period.

In 1844, at the age of 25, George McManus took charge of his first ship. Over the next 20 years, he acquired a reputation as a highly respected captain, navigator, and businessman. Early in his career, he commanded vessels that brought immigrants to America. In 1851 he sailed the Monterey from Le Havre to New York. Its passenger list records the names of 193 German, Prussian, and Swiss men, women, and children. The next year Captain McManus brought another group of immigrants from Liverpool to New York on his brother’s ship Esmeralda.

While much of McManus’s life was spent at sea, he found time for a family in Brunswick. In 1841 he married Abigail Stone. His daughters Ellen and Alice were born in 1847 and 1851, respectively. Abigail Stone McManus died three-and-a-half months after Alice’s birth, and baby Alice died soon after. In 1859, McManus married Mary Lucilla Coburn, who bore two sons, Warren C. McManus in 1861 and George R. McManus in 1862.

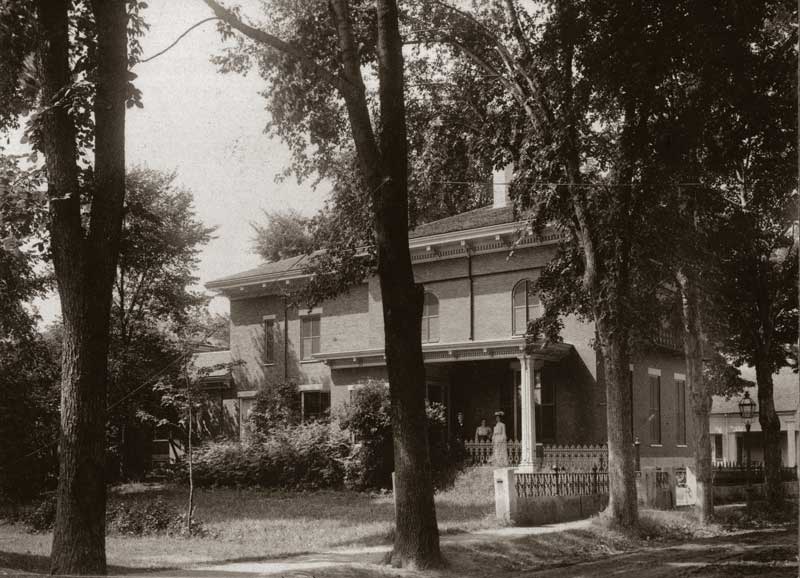

This view of the house was taken in 1890, long after Captain George McManus had gone down with his ship at sea and the lack of income forced his widow to sell the mansion to local grocer Joshua Lufkin. Image courtesy Pejepscot History Center

This view of the house was taken in 1890, long after Captain George McManus had gone down with his ship at sea and the lack of income forced his widow to sell the mansion to local grocer Joshua Lufkin. Image courtesy Pejepscot History Center

Perhaps anticipating that he would eventually remarry, on September 8, 1856, Captain McManus purchased property on the south side of Lincoln Street in Brunswick for $850. The property was one of 14 lots created between Maine and Union streets and sold between June 1843 and September 1844. By 1846, eight brick or frame Greek Revival houses were under construction on the street, and by the time George McManus bought his lot in 1856, much of this fashionable downtown neighborhood was well developed. The Brunswick Telegraph traced the progress of his house’s construction in 1858:

April 23, 1858:

Captain George McManus has the foundation laid for a first-class brick house on Lincoln Street, south side.

July 2, 1858:

The house of Captain George McManus on Lincoln Street is now far advanced and towards completion, and it is a building which will prove an ornament to the street and the village. In its design some little effort has been made to carry out architectural ideas, and the model is a departure (and this is an improvement) from the standard styles of two stories and a story and a half, painted white with green blinds, which disfigures every section of the village.

July 9, 1858:

The front of Captain George McManus’s house, and that portion of the Captain Skolfields’ which is up, show the quality of the Portland dry pressed brick. They are a dark red color, quite smooth, and of good size. The work of laying the brick on the houses in question has been well done, and the fronts will present an appearance altogether different from anything that we have previously had in town.

The Brunswick Telegraph’s positive comments on the McManus residence’s architecture refer to its Italianate style. While the recessed panel brick treatment of the front and side walls is characteristically Greek Revival, the arched second-story windows and the overhanging bracketed cornice of the entrance porch and the roof are Italian in design. Likewise, the interior plan presents a novel approach. The entrance hall on the east side connects to a spacious front parlor and a dining room. The balance of the first floor is devoted to a kitchen and the captain’s office, through which the carriage house is accessed. The second floor accommodates two large and two smaller bedrooms.

Mary Lucilla McManus. Image courtesy Pejepscot History CenterWhile several neighboring houses are brick, the scale and style of the McManus House, coupled with its handsome pressed brick exterior, make it the grandest house on Lincoln Street. The question of who designed the house remains a mystery. One clue points to the Captains Alfred and Samuel Skolfield’s imposing duplex on Park Row that was also built the same year of Portland pressed brick and which shares the McManus’s Greek Revival panel brick treatment and Italianate features. While the architect of the Skolfield houses remains unidentified, the contractor was R. T. D. Melcher, son of the Brunswick architect-builder Samuel Melcher III. The younger Melcher billed the Skolfields $15,751.61 for his work.

Mary Lucilla McManus. Image courtesy Pejepscot History CenterWhile several neighboring houses are brick, the scale and style of the McManus House, coupled with its handsome pressed brick exterior, make it the grandest house on Lincoln Street. The question of who designed the house remains a mystery. One clue points to the Captains Alfred and Samuel Skolfield’s imposing duplex on Park Row that was also built the same year of Portland pressed brick and which shares the McManus’s Greek Revival panel brick treatment and Italianate features. While the architect of the Skolfield houses remains unidentified, the contractor was R. T. D. Melcher, son of the Brunswick architect-builder Samuel Melcher III. The younger Melcher billed the Skolfields $15,751.61 for his work.

While not as costly as the Skolfield houses, the construction of McManus’s new home apparently required more funds than the captain had at his disposal. On August 5, 1858, he mortgaged his house and land for $4,800. Such was his business acumen that he repaid the loan in full on January 30, 1860.

The construction of the McManus House coincided with the launching of a new ship, the Daniel L. Choate, which the captain would command for the next six years. Owned by and named for a prominent Portland captain, the Choate was built at the Soule shipyard in Freeport in 1858. She was valued at $75,000, and her tonnage was variously reported at 919 and 950 tons. With George McManus on the quarterdeck, the Choate left her home port of Portland in August 1858 bound for St. George, New Brunswick. There, she ran aground, filled with water, and had to undergo $10,000 in repairs.

After repairs were completed, the Choate sailed to Boston and began a series of transatlantic crossings between Boston and Liverpool in 1858 and 1859. In the fall of 1859, she engaged in the cotton trade between southern ports and England and France. Between November 1859 and May 1861, she made regular trips between Mobile and New Orleans and Liverpool and Le Havre.

In the spring of 1861, McManus left the sea for a year to complete his new home and settle his family. The timing was propitious, for the Civil War had curtailed the cotton trade, and Confederate raiders made Atlantic passages hazardous for Northern vessels. When Captain McManus resumed command of the Daniel L. Choate, he avoided the Atlantic routes in favor of the Far Eastern rice trade. Leaving Portland in July 1862, he sailed for London, arriving in September. From there he began nearly two years of voyages between England and European ports and the Burmese cities of Akyab and Bassein.

In October 1863, the Choate left Antwerp, Belgium, for Burma. Arriving in Bassein on February 23, 1864, Captain McManus spent a month loading a cargo of rice and departed for Falmouth, England on March 28th. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the Choate sailed up the west coast of Africa, where she encountered a heavy gale in June that claimed the vessel and all but one of her crew. According to the sole survivor:

The crew had consisted of 19 men and a stewardess. The vessel had encountered very hard weather, which caused her to leak very much, and as the weather got worse, the leak rapidly increased, until the pumps were completely choked with rice. On June 15 the crew began throwing the cargo overboard in large quantities in the hope of saving the ship. As the day advanced, the weather became worse, and a heavy sea having struck her, carried away the deck house. Shortly afterwards the ship gave a heavy plunge and settled down, giving scarcely time for a few men to get into one of the boats. This boat is supposed to have been drawn down with the ship.

It was not until late August that Captain McManus’s family received the official report of the loss of McManus, most of his crew, and his vessel in a letter from the U.S. Consul at St. Helena written on July 15. Forwarded to Brunswick from the State Department in Washington, D.C., the letter contained the surviving crew member’s account of the Choate’s sinking. On September 1, two Portland newspapers, the Daily Press and the Daily Eastern Argus, published the report, and the Brunswick Telegraph mentioned it the following day.

Still holding out hope for news of a rescue, Captain McManus’s family delayed the funeral until January 8, 1865. That day a large congregation gathered at the Mason Street Unitarian Church, where the Reverend Amos D. Wheeler led a service with the appropriate theme from Psalm 107—“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters”—and in his eulogy, he noted that in the captain’s last letters to his wife, he had expressed regret for his nearly two-year separation from his family and his intention to retire from the sea once his current voyage was completed.

The McManus family was all too familiar with the risks of the seafaring life. Before the sinking of the Choate claimed both George McManus and his nephew Isaac McKaid (one of the crew members), his brothers Captain Asa McManus and Captain Nicholas McManus, as well as his sister Elizabeth McManus Curtis died at sea.

Mary Lucille McManus, age 23, found herself widowed with an eighteen-year-old stepdaughter Ellen and two young sons, Warren, age 3, and George, age 2. Her husband’s will directed that her father administer the estate and serve as guardian of the boys. As a result, Mary had to petition the estate for an allowance to operate her household. Soon the dynamics changed again as Mary’s father, mother, and younger brother and sister joined her and her children at 11 Lincoln Street.

Without Captain McManus’s income, financial pressures began to mount. In 1866 the estate sold land in Brunswick that the captain had acquired to farm in his retirement. The next year the Lincoln Street house was advertised for sale, but it found no immediate buyer. Not until 1873 was it purchased by Joshua Lufkin, a local grocer, for $2,862, well below its value. In 1871 Mary McManus had married Stephen Morrill Newman, a graduate of Bowdoin College and Andover Newton Theological Seminary. That year the couple along with her sons moved to Taunton, Massachusetts, where Reverend Newman served as the minister of the Trinitarian Congregational Church.

The house at 11 Lincoln Street remained in the Lufkin family until 1927, when it was acquired by C. Earle Richardson, M.D., the first director of the Brunswick Hospital. In 1962 Dr. Richardson willed the house to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for a parish rectory. Twelve years later the church sold the property to the Pejepscot Historical Society for its headquarters and museum. When the society was gifted the Skolfield-Whittier House in 1982, the McManus House returned to a progression of private owners.

George W. McManus’s house has stood at 11 Lincoln Street for more than 160 years, a testament to the aspirations of a Brunswick captain whose story is that of many brave Maine men in the age of sail, who went down to the sea in ships to pit their navigational skills against an unforgiving ocean.

A native of Portland, Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. directed the Maine Historic Preservation Commission from 1976 to 2015 and has served as Maine State Historian since 2004.