The only known portrait of Josiah Shackford was painted by John Singleton Copley in July 1776. Image courtesy Willis Henry Auctions, Inc. As a kid, sailing the coast of Maine and New Hampshire on my family’s 28-foot Sea Sprite, I often fantasized about solo sailing, captivated by stories of young people like Jessica Watson, only a few years older than myself, who had single-handedly captained her own boat around the world. Sitting in the cockpit of Flying Goose, my dad would tease me, joking that instead of returning home for dinner, we were sailing straight out to sea, “all the way to Portugal!” While we always did return to our mooring, I often pictured myself captaining my own boat, facing a horizon of towering swells, and intense solitude. What would it be like, to sail alone across an ocean?

The only known portrait of Josiah Shackford was painted by John Singleton Copley in July 1776. Image courtesy Willis Henry Auctions, Inc. As a kid, sailing the coast of Maine and New Hampshire on my family’s 28-foot Sea Sprite, I often fantasized about solo sailing, captivated by stories of young people like Jessica Watson, only a few years older than myself, who had single-handedly captained her own boat around the world. Sitting in the cockpit of Flying Goose, my dad would tease me, joking that instead of returning home for dinner, we were sailing straight out to sea, “all the way to Portugal!” While we always did return to our mooring, I often pictured myself captaining my own boat, facing a horizon of towering swells, and intense solitude. What would it be like, to sail alone across an ocean?

Recently, I learned that the first ever to do so may have hailed from my home port. Josiah Shackford, a native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, may well have been the first known person to sail solo across the Atlantic. He did this in 1787, sailing a 15-ton sloop with only his watchdog Bruno for company from Bordeaux, France, to Surinam in 35 days. You’ve most likely never heard of him. While the Guinness Book of World Records considers Shackford to be the first to complete a transatlantic alone, most others, including the World Sailing Speed Record Council, credit the feat to Alfred “Centennial” Johnson, who sailed from Maine to Wales a century later.

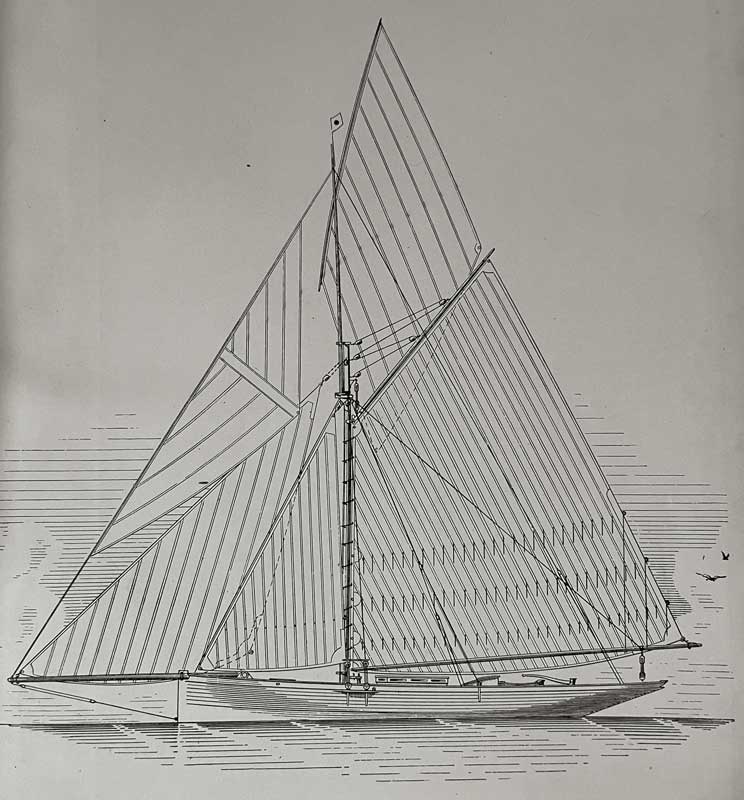

Shackford sailed alone in a 15-ton cutter, similar perhaps to this boat drawn by C.P. Kunhardt in his book Small Yachts, Their Design and Construction.News of Shackford’s transatlantic crossing is scattered among various newspapers, the first featuring the story in 1787. Some 70 years later, Portsmouth Editor writer Charles Brewster produced what is likely the most definitive account of Shackford’s life and voyage. While some sources published identical accounts, others included additional details and it is unclear who copied whom. The facts remain a little murky. According to Brewster and others, from a young age Shackford dreamed of traveling far from home. He maintained a close relationship with his mother, to whom he would relate his dreams of visiting far off islands. After her death, he began his career as a mariner, sailing regularly between Portsmouth, New York City, and the Caribbean.

Shackford sailed alone in a 15-ton cutter, similar perhaps to this boat drawn by C.P. Kunhardt in his book Small Yachts, Their Design and Construction.News of Shackford’s transatlantic crossing is scattered among various newspapers, the first featuring the story in 1787. Some 70 years later, Portsmouth Editor writer Charles Brewster produced what is likely the most definitive account of Shackford’s life and voyage. While some sources published identical accounts, others included additional details and it is unclear who copied whom. The facts remain a little murky. According to Brewster and others, from a young age Shackford dreamed of traveling far from home. He maintained a close relationship with his mother, to whom he would relate his dreams of visiting far off islands. After her death, he began his career as a mariner, sailing regularly between Portsmouth, New York City, and the Caribbean.

As a young adult, Shackford married his stepsister Deborah Marshall. In 1776, he joined the U.S. Navy, and fought in the American Revolution as a lieutenant on the USS Raleigh and master of the privateer ship Diana. As he was often away from home, his marriage with Marshall seems to have been rocky. Sailing regularly between New Hampshire and New York City, the captain attempted to convince Deborah to move to New York with him. But she refused to leave her sick mother and so the two lived separately and, reportedly, did not stay in touch. Meanwhile, Shackford sailed down to Surinam where he secured a boat bound for Europe; and in 1786, he successfully crossed the Atlantic with his crew. Upon arriving in Bordeaux, France, the recipients of the cargo he carried were so pleased with his delivery that they gifted him a 15-ton sloop. With his own boat and a desire to return to the Americas, Shackford pointed his bow west.

“See him on the boisterous mid-ocean alone in his little bark a thousand miles from any land,” wrote Charles Brewster in his Rambles About Portsmouth in 1869, “without a human being to consult when awake, or to aid in keeping watch while he slept; without a hand to aid when the storm beat upon him, and his little boat is hit between mountain swells!”

Shackford served as the commissioned lieutenant of the Continental frigate Raleigh, a 32-gun frigate authorized by the Continental Congress in 1775. The ship is featured on the New Hampshire state flag. Image courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command

Shackford served as the commissioned lieutenant of the Continental frigate Raleigh, a 32-gun frigate authorized by the Continental Congress in 1775. The ship is featured on the New Hampshire state flag. Image courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command

As the story goes, Shackford arrived again in Surinam after 35 days at sea. Bruno had died in passage. Alone on his boat, he was greeted with suspicion and accusations of mutiny. Officials refused to accept that Shackford had completed the voyage with no crew until he produced his journal and papers. To prove his competence as a solo captain, he sailed his boat out and back into the harbor. His accomplishment was finally believed when a message arrived from Europe, confirming his departure from Bordeaux more than a month earlier. After settling the dispute, and without any fanfare, Shackford picked up a couple of crew and set sail for St. Barts to the north. From the Caribbean, he continued on back to Portsmouth, completing his transatlantic venture.

While Shackford completed the transatlantic voyage single-handedly, he did not seem intent on setting a record. In fact, according to most sources, he was supposed to be joined by a crewmember. As he edged his boat out of the harbor, however, his crew apparently became frightened of the long voyage ahead, jumped from the vessel and swam to a nearby pilot boat. And so Shackford sailed on, with only Bruno.

A view of Portsmouth, N.H., and the Piscataqua River as they would have looked in Shackford’s day, from Atlantic Neptune, 1791, by Joseph Des Barres. Still, this vague tale of the first known man to sail solo across the Atlantic Ocean leaves much to the imagination. Shackford himself left no records of the trip and details must be pieced together from multiple sources. On May 2, 1787, The Essex Journal and New Hampshire Packet mentioned the voyage briefly, asserting their source to be a gentleman at New York, “he having it from such authority as puts the truth quite out of dispute.” The news item read as follows: “A Mr. Shackford from time since from Piscataqua, having the misfortune of discontent with his wife, left that place for Surinam, on his arrival there, he left the vessel he had sailed in, and took the command of one for Europe. He performed his voyage and gave such a satisfaction to his owner, that they gave him a cutter-built sloop of about 15 tons; with her he returned to Surinam ALONE after a passage of 35 days; when he arrived there the novelty of the expedition excited unusual surprise, so far as to induce the government to take notice of the fact.”

A view of Portsmouth, N.H., and the Piscataqua River as they would have looked in Shackford’s day, from Atlantic Neptune, 1791, by Joseph Des Barres. Still, this vague tale of the first known man to sail solo across the Atlantic Ocean leaves much to the imagination. Shackford himself left no records of the trip and details must be pieced together from multiple sources. On May 2, 1787, The Essex Journal and New Hampshire Packet mentioned the voyage briefly, asserting their source to be a gentleman at New York, “he having it from such authority as puts the truth quite out of dispute.” The news item read as follows: “A Mr. Shackford from time since from Piscataqua, having the misfortune of discontent with his wife, left that place for Surinam, on his arrival there, he left the vessel he had sailed in, and took the command of one for Europe. He performed his voyage and gave such a satisfaction to his owner, that they gave him a cutter-built sloop of about 15 tons; with her he returned to Surinam ALONE after a passage of 35 days; when he arrived there the novelty of the expedition excited unusual surprise, so far as to induce the government to take notice of the fact.”

Thirty-six years later in 1823, Shackford’s transatlantic feat reappeared in the New York Gazette, along with the news that another mariner would be attempting the crossing. This story was also published in the New Hampshire Gazette in March of that same year. In this rendition of the story, when asked how he slept while underway, Captain Shackford retorted, “With my eyes shut.” Then, in 1832, the Sailor’s Magazine and Naval Journal printed a story detailing a visit between Shackford and Sir Joseph Banks in London during which the two were said to have argued about whether they believed elephants to have tongues. According to this story, when asked about his route, Shackford admitted to guessing, assuring “that was right enough for one whose time was his own, and, who owned the craft he was in, and had plenty of provisions on board.” The tale, which was reprinted in other papers, is the only one to include further details of Shackford’s voyage, and despite its intrigue, the part involving Sir Banks is likely fictional.

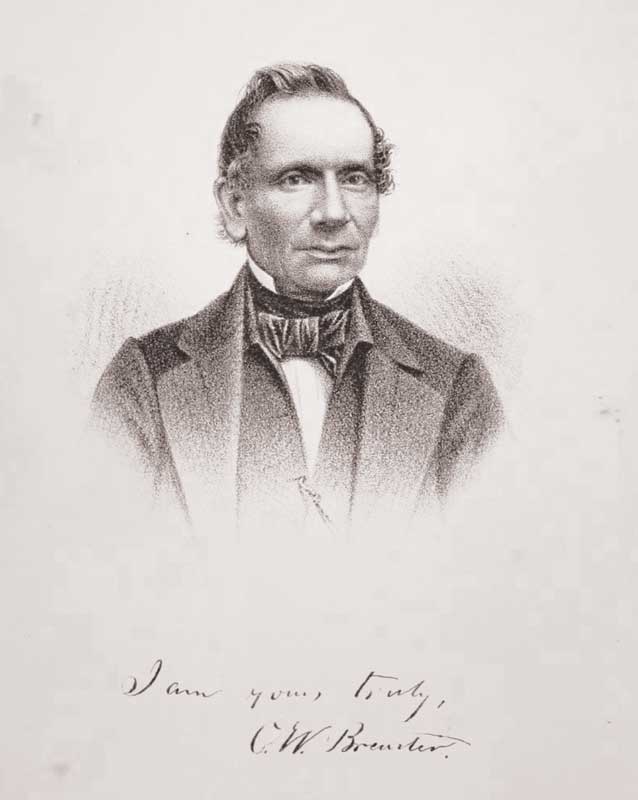

Portsmouth Historian Charles Brewster wrote for the Portsmouth Editor for 50 years. From Rambles about Portsmouth, Charles Brewster, 1869. Image courtesy Naval History and Heritage CommandA number of sources detail Shackford’s later life, including Brewster’s Rambles About Portsmouth. After returning to New Hampshire, the captain again tried to convince his wife to relocate, this time to Ohio. Again, she refused, so Shackford left the sea behind and headed west on his own. Together with Henry Massie, he formed the town of Portsmouth, Ohio (named after his birthplace) in 1802. He maintained a peculiar and enigmatic reputation around town and lived alone in a two-story house, the second floor of which was finished to look like the interior of a ship. The story goes that he never allowed a woman inside. Whether Shackford was widowed or a bachelor remained a focal point of local gossip. Although Deborah Marshall eventually sent him a letter, he did not respond, and she never ventured west to rejoin her husband. On July 26th, 1829, Josiah Shackford died at age 93.

Portsmouth Historian Charles Brewster wrote for the Portsmouth Editor for 50 years. From Rambles about Portsmouth, Charles Brewster, 1869. Image courtesy Naval History and Heritage CommandA number of sources detail Shackford’s later life, including Brewster’s Rambles About Portsmouth. After returning to New Hampshire, the captain again tried to convince his wife to relocate, this time to Ohio. Again, she refused, so Shackford left the sea behind and headed west on his own. Together with Henry Massie, he formed the town of Portsmouth, Ohio (named after his birthplace) in 1802. He maintained a peculiar and enigmatic reputation around town and lived alone in a two-story house, the second floor of which was finished to look like the interior of a ship. The story goes that he never allowed a woman inside. Whether Shackford was widowed or a bachelor remained a focal point of local gossip. Although Deborah Marshall eventually sent him a letter, he did not respond, and she never ventured west to rejoin her husband. On July 26th, 1829, Josiah Shackford died at age 93.

Was Shackford really the first person to single-handedly sail across the Atlantic? Did his crew really jump ship at the harbor mouth? What happened to Bruno? Or did Charles Brewster spin a yarn eventually taken to be fact? The sea seems to have swallowed all certainty.

Shackford’s gravestone at the Greenlawn Cemetery in Portsmouth, Ohio. The inscription reads, “Of no distemper; of no blast herlied, But fell like autumn frail, that mellowed long, Even wondered at, because it fell in sooner. Time seemed to wind him up, for fourscore years. Yet briskly ran he on, twelve winters more, Till like a clock, worn out with eating time. The wheels of weary life, stood still.”This much we know: Josiah Shackford was a real person and sea captain, from Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Shipping records confirm his travel between New Hampshire and the Caribbean in the 1770s. His grave lies in Portsmouth, Ohio. The rest lies in a thin paper trail of newspaper articles and seafaring tales. Indeed, the rugged solo mariner is ever romanticized. To imagine Shackford and Bruno careening across the Atlantic on a small sloop is to tap into a primal longing for the freedom and lawlessness of the sea.

Shackford’s gravestone at the Greenlawn Cemetery in Portsmouth, Ohio. The inscription reads, “Of no distemper; of no blast herlied, But fell like autumn frail, that mellowed long, Even wondered at, because it fell in sooner. Time seemed to wind him up, for fourscore years. Yet briskly ran he on, twelve winters more, Till like a clock, worn out with eating time. The wheels of weary life, stood still.”This much we know: Josiah Shackford was a real person and sea captain, from Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Shipping records confirm his travel between New Hampshire and the Caribbean in the 1770s. His grave lies in Portsmouth, Ohio. The rest lies in a thin paper trail of newspaper articles and seafaring tales. Indeed, the rugged solo mariner is ever romanticized. To imagine Shackford and Bruno careening across the Atlantic on a small sloop is to tap into a primal longing for the freedom and lawlessness of the sea.

Today, two and a half centuries later, my family moors our boat in Kittery Point, Maine, at the mouth of the Piscataqua River, across from Portsmouth. Here, treacherous currents churn and the 2KR buoy bell rings. Occasionally, ocean going tankers hailing from ports around the world creep by Whaleback Light and up the river to unload their cargo. In Portsmouth today, historic brick buildings neighbor rows of shipping containers and floats of red and black tugs. Colonial houses, painted gray, yellow, tan and dark red line cobblestone streets, overlooking the small shipping port. According to Brewster, the Shackford mansion, which once stood on State Street and was home to Josiah Shackford Sr. and his wife Eleanor Marshall, burned down in 1813.

Around 1787, the time of Shackford’s voyage, I imagine the mouth of the Piscataqua River, our shared home port, to have been crowded with wooden vessels, their sheets taut and their canvas sails thrumming with wind. The daydreamer in me is inclined to believe that Shackford really did complete his solo passage. I see no harm in leaning into the legend. Although sailing and navigation technology have drastically improved, the allure of crossing an ocean remains ever present in the minds of novice and experienced sailors alike. While the story of the first man to do so alone remains elusive, the small shipping port of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, home to the pioneering Josiah Shackford, has as good a claim as any other harbor as the birthplace of such a historic voyage.

✮

Robin Potter is a senior at Middlebury College in Vermont. She will be embarking on her first transatlantic this summer, as crew aboard the fifty-foot Able, Mistral. Many thanks to Richard King, Robin Silva, and Trenton Carls for their help with this article.