All photos courtesy Krisanne Baker

In Krisanne Baker’s Study for Cuttlefish Mating Dance, 2020, a pair of the squid-like creatures hovers among radiant coral. Oil and phosphorescent pigments on canvas, 16 x 20 in.

In Krisanne Baker’s Study for Cuttlefish Mating Dance, 2020, a pair of the squid-like creatures hovers among radiant coral. Oil and phosphorescent pigments on canvas, 16 x 20 in.

Where many Maine painters respond to the landscape around them, Krisanne Baker dons a mask and snorkel and slips on fins to follow her muse below the water’s surface.

During a residency on Great Spruce Head Island in June 2015, in what she describes as “those pre-My Octopus Teacher days,” Baker snorkeled off the island’s North Beach at high tide “as it’s a bit warmer.” As she circumswam conical masses of Ascophyllum nodosum, a cold-water seaweed, she came face to face with a small rock crab. “We both moved backward in surprise,” she recalled; “I think I even voiced a shout into my snorkel.”

After encountering the crab on consecutive days Baker had a good vision of the scene and had her paints and panel waiting on the shore to get right to work. The resulting painting shows the small crustacean clinging to the holdfast at the base of a clump of swaying rockweed.

Baker loves these types of “lingerings” during which she can spend time observing the details of undersea inhabitants while feeling “the sensations of the water, the currents, the temperature, the constantly shifting light.” She seeks to convey these impressions in her work, a mission she considers “a joyful challenge.”

Baker snorkels the intertidal waters while an artist-in-residence at the Shoals Marine Laboratories on Appledore Island in 2021.

Baker snorkels the intertidal waters while an artist-in-residence at the Shoals Marine Laboratories on Appledore Island in 2021.

Baker does not wear a wetsuit. Having swum as a kid in the ocean north of Boston, she is used to the cold. That said, she only snorkels in Maine June through September. “After that,” she noted, “it gets painful and takes away the joy.”

Over the past 10 or so years, Baker has taken to warmer waters to indulge in her snorkeling obsession and expand her ocean-art enterprise. She started going to a small town on the edge of the National Reef Park of Puerto Morelos on the Caribbean coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. The park protects a portion of the Mesoamerican Reef, the second largest coral formation in the world.

Baker’s High Tide with Inhabitant, Great Spruce Head Island, 2018, features a small rock crab clinging to the base of some rock weed. Oil on panel, 12 x 12 in.

Baker’s High Tide with Inhabitant, Great Spruce Head Island, 2018, features a small rock crab clinging to the base of some rock weed. Oil on panel, 12 x 12 in.

Having found her “happy winter spot,” Baker returned nearly every year to snorkel to her heart’s delight. The experience has led to a series of reef-based paintings that include a lively rendering of a pair of cuttlefish, a squid-like mollusk, in a mating ritual.

Circling some coral heads near shore one day, Baker noticed the aqua-dynamic creatures “dance back and forth past each other, then reverse and swing back in an arc.” Startled by her presence, the “two lovers” jetted a few feet away and hovered, sizing her up. “I obliged them by remaining fairly still except for the sway of the current,” she recounted. To her delight, the cuttlefish returned to the spot they had previously occupied and resumed their dance.

Baker captures the beauty of microscopic organisms in Plankton Evening Dreams, Appledore Island, 2021. Oil and phosphorescent pigments on panel, 12 x 12 in.

Baker captures the beauty of microscopic organisms in Plankton Evening Dreams, Appledore Island, 2021. Oil and phosphorescent pigments on panel, 12 x 12 in.

After observing them for some 15 minutes, Baker was able to paint what she’d witnessed. That swirling image made with phosphorescent pigments shows the cuttlefish couple swimming side by side in the luminous tropical waters.

Baker’s artwork has been focused on water quality and phytoplankton for many years. Through a series of artist residencies, she has had the opportunity to expand her understanding of the sea as well as her subject matter and artistic practice. She has spent time at the Shoals Marine Laboratory on Appledore Island, the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay, and the Wells Reserve at Laudholm Farm, among others.

During the last-named residency in 2023, Baker studied the migration of the blue crab, which has been moving farther north each year due to warming waters related to climate change. She joined researchers on the Webhannet River marshes to collect data and samples from the Wells Reserve traps.

As part of her residency, Baker drew a live crab in the Maine Coast Ecology Center gallery so that visitors could better understand her process and have a view into the science lab at the same time. Her exhibition “subMerge: An Oceanic Relationship” featured underwater paintings and a glass plankton installation. It was a huge hit.

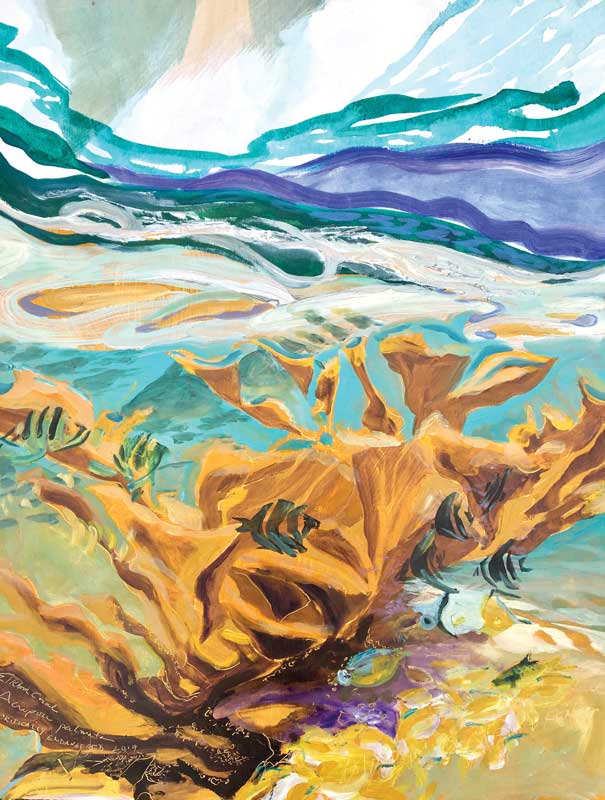

An important reef-building species, elkhorn coral has declined significantly in recent years. Krisanne Baker, Critically Endangered: Elkhorn Coral, 2020, oil on panel, 30 x 24 in.

An important reef-building species, elkhorn coral has declined significantly in recent years. Krisanne Baker, Critically Endangered: Elkhorn Coral, 2020, oil on panel, 30 x 24 in.

Born on the north shore of Boston, Baker moved to Antrim, New Hampshire, for a few years while her father was Dean of Students at Nathanial Hawthorne College. To keep the family close to the ocean, he bought a 19-foot True Rocket sailboat built by Arthur True of Amesbury, Massachusetts. Every weekend they drove to Ipswich to go sailing. “We went wherever the wind took us,” Baker recalled. She credits this early immersion on and in the sea (she was “one of those swimming infants”) for shaping her love of the ocean.

These underwater experiences took on additional meaning when, in her 40s, Baker learned that she was a highly functioning autistic. That knowledge helped explain why she loved being out on the water with her father—and in the sea. “People with anxiety are known to feel comforted by being underwater,” she explained. “The pressure surrounding your body is soothing, yet you feel free; sounds and light are muffled, and everything seems to move in slow motion.”

As a teenager living with her family on Cape Cod, Baker followed her brother’s advice to take Peter Auger’s ecology class at Barnstable High School. Auger led his students on weekend trips to a dune shack on nearby Sandy Neck. There they studied diamondback terrapin turtles, on whose behavior he is an authority, and tracked the erosion and shifting of the sand dunes.

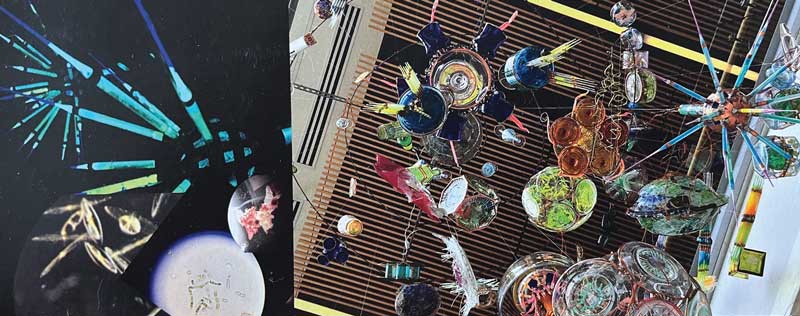

These are two shots of Baker’s “Ocean Breathing” installation at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in 2019-2021, featuring 100-plus upcycled glass sculptures of mutating phytoplankton. Installation: 25 (h) x 9 (d) x 9 (w); individual sculptures: dimensions variable.

These are two shots of Baker’s “Ocean Breathing” installation at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in 2019-2021, featuring 100-plus upcycled glass sculptures of mutating phytoplankton. Installation: 25 (h) x 9 (d) x 9 (w); individual sculptures: dimensions variable.

Not only did Auger turn Baker on to ocean ecology, he introduced her to black-and-white photography. Spending time in the darkroom—a lab storage closet—led her to video classes at the Rhode Island School of Design where she did her first experiments with underwater video and multi-media installations.

Other mentors along the way have included artists Dont Rhine and Aviva Rahmani, both of whom encouraged Baker to make activism a part of her artistic mission. According to Baker, Rahmani is famous on Vinalhaven for having bought the town dump near the waterfront and remediated the land by planting it with healing circles of native species.

After an abbreviated stint with the Core Residency Program in Houston, Texas, Baker returned to the East Coast, settling in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in 1984. For a time, she worked in a Madison Avenue gallery as an executive secretary.

In 1989 Baker and her partner moved to Maine. “I was just a New England girl,” she explained, “who had had her fill of New York City and missed New England life.” She also wanted to be close to the ocean. Aside from residencies, she has been a Mainer ever since.

Baker researched and drew from live plankton samples as visiting artist in residence at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, 2018-2019.In 2006 Baker enrolled in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, studying with painter Dozier Bell. An admirer of Bell’s “ephemerally sublime” landscapes, she was delighted to discover the painter lived right up the street from her in Waldoboro.

Baker researched and drew from live plankton samples as visiting artist in residence at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, 2018-2019.In 2006 Baker enrolled in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, studying with painter Dozier Bell. An admirer of Bell’s “ephemerally sublime” landscapes, she was delighted to discover the painter lived right up the street from her in Waldoboro.

Baker recently retired after 30 years of teaching art in Maine public schools, including Medomak Valley High School. During that time, she developed an award-winning curriculum for her high school students called “Gulf of Maine: Dare to Care” inspired by her passion for ocean health. Cultivating compassion and respect for other creatures through art-making is the main goal of her teaching—to help foster future stewards of the planet. She has been pleased to see some of her students go into environmental law and marine biology.

Baker continues to share her knowledge and passion. This past February, she traveled to the island of Koh Mak in Thailand to provide art and “reef ecology experientials,” including snorkeling, to local youth through the Coral Gardeners reef restoration program. Funding for the trip derived in part from sales of her artwork in 2023.

As an ocean art advocate educator, Baker taught the Thai students a modified version of her high school ocean curriculum. Marine biologist Christopher Koerber, who is part of the Boynton clan of Monhegan Island, engaged the youngsters with reef ecology and restoration practices. Baker and her colleague, New Haven, Connecticut-based educator and Monhegan artist Mary Pendergast, then guided them in creating ceramic work depicting their favorite corals and reef creatures.

These days, climate change is front and center in Baker’s art-making. She is an active member of several different groups of artists working with climate issues, in Boston, New York, and elsewhere. This fall she will be guest curator for a show at Cape Cod Community College near where she grew up.

When Baker lived in Brooklyn, she used to take the subway to Coney Island to walk the beaches in the off season. While in Rome for a semester at RISD, she spent a lot of time on the Tiber River. Wherever she goes, she seeks out water, which is life and art—and pretty much everything.

✮

You can find more of Baker’s work on her website, krisannebaker.com. She has shown at Caldbeck Gallery in Rockland, Moss Galleries in Falmouth, University of New England, and Husson University, among many other venues.

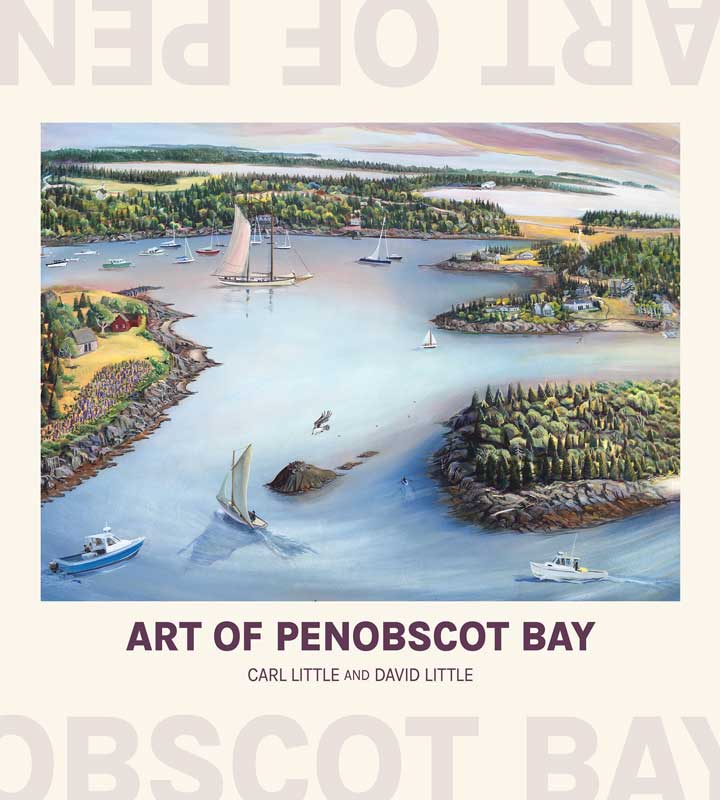

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. One of Krisanne Baker’s underwater painting is reproduced in Art of Penobscot Bay (Islandport Press), he and his brother David Little’s latest collaboration.

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. One of Krisanne Baker’s underwater painting is reproduced in Art of Penobscot Bay (Islandport Press), he and his brother David Little’s latest collaboration.