Photographs by Ben Krebs

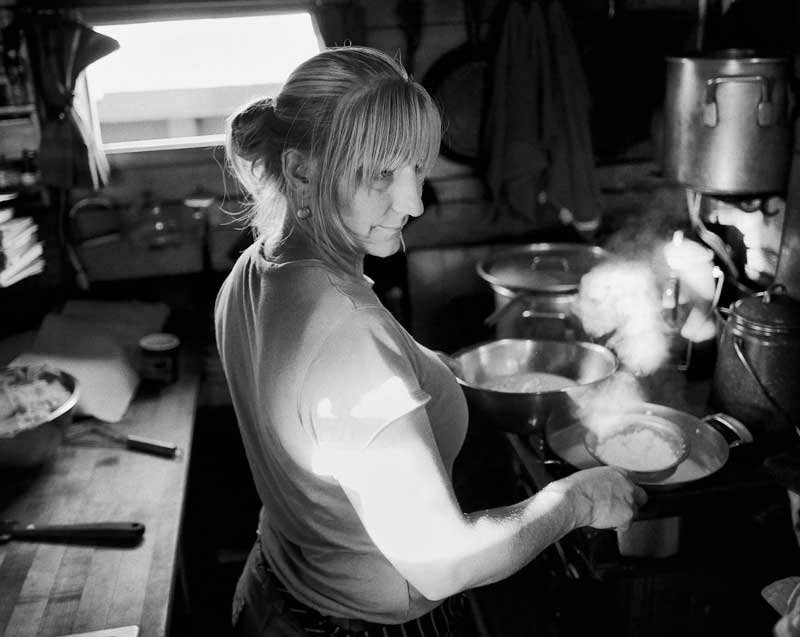

Schooner captain and chef Annie Mahle, shown here in her schooner’s galley, is releasing her fourth cookbook: The Tiny Kitchen Cookbook: Strategies and Recipes for Creating Amazing Meals in Small Cooking Spaces. The book follows previous releases with stories, recipes, and crafting projects centered around the windjammer life.

Schooner captain and chef Annie Mahle, shown here in her schooner’s galley, is releasing her fourth cookbook: The Tiny Kitchen Cookbook: Strategies and Recipes for Creating Amazing Meals in Small Cooking Spaces. The book follows previous releases with stories, recipes, and crafting projects centered around the windjammer life.

“The first thing you learn when cooking on a sailboat is how to protect whatever is on the stove from falling off the stove,” said Captain Annie Mahle, who sailed the Schooner J. & E. Riggin out of Rockland, Maine, with her husband, Captain Jon Finger.

She continued, “It doesn’t take you too many times with the turkey sliding off the stove and across the galley sole before you realize, ‘Okay, we’re going to have a different plan.’”

Mahle spoke with long experience and the good humor of someone who has successfully figured out that plan—in tight confines with hundreds of pounds of raw ingredients for as many as 24 guests and six crew members, and accounting for a range of dietary requirements.

Not only that, she’s developed scores of recipes that resulted in her Sugar & Salt cookbook series, a collection of recipes, crafts, thoughts, and stories from an adventurous life off the Maine coast. Her cooking, recipes, and cookbooks have been highlighted on the Today Show and Throwdown with Bobby Flay. Her food and the Riggin have been featured in dozens of national media outlets, including the Food Network, Traditional Home Magazine, Family Circle, Women’s Day, Boston Globe, and Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors. Yankee Magazine has twice named the Riggin one of the “Top 10 Places to have Dinner with a View in Maine.”

Mahle sources local ingredients and preps them in the Riggin’s 6- by 8-foot galley.

Mahle sources local ingredients and preps them in the Riggin’s 6- by 8-foot galley.

And yet, Mahle began her career not knowing how to sail and with little culinary training. “When I graduated from college, I wouldn’t have called myself a chef, a writer, a business owner, a sailor, a mom or a wife,” she said. “I was not expecting to be any of those things.”

Raised near Detroit, Michigan, Mahle decided she wanted to learn to sail after graduating from Michigan State University. An acquaintance connected her with Captains Ellen and Ken Barnes, a couple who have long owned windjammers in midcoast Maine. They offered a job the day she called. Mahle drove 16 hours to Maine, got up at 4 the next morning, went to work as mess cook—and quickly developed a passion for cooking. (Her first day on the job, Mahle met Finger, who served as the mate.)

Mahle went from being mess cook to head cook on the windjammers and to private chef on a Caribbean yacht. She further developed her skills as a sous chef to classically trained Swiss chef Hans Bucher and at the Culinary Institute of America.

But Maine beckoned, especially when Mahle and Finger were ready to start a family. They decided to buy a windjammer, with Mahle running the galley.

Annie Mahle and Jon Finger ran the schooner J. & E. Riggin for many years. The couple recently sold the Riggin to former crew members

Annie Mahle and Jon Finger ran the schooner J. & E. Riggin for many years. The couple recently sold the Riggin to former crew members

The Riggin, she said, is essentially a floating restaurant and bed-and-breakfast. Sailing all summer long on multi-day trips in and around Penobscot Bay, she developed sophisticated menus over nearly 25 years that include main courses, sides, salads, baked goods, and drinks, using ingredients that she grows herself or sources locally.

Cooking on a sailboat involves interesting logistics in a 6- by 8-foot galley that’s partly occupied by a 3- by 4-foot woodburning stove. In this space, smaller than a food truck, she and her assistant serve 30 people breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day.

Pre-dawn hours are spent making the day’s baked goods, including breads, sticky buns, and desserts.

Pre-dawn hours are spent making the day’s baked goods, including breads, sticky buns, and desserts.

She lacks the conveniences of a modern kitchen—microwave, freezer, walk-in refrigerator, or much storage space at all. Her range is a woodstove, the fire built up each morning before dawn, tended throughout the day. Without electricity, everything is made by hand—the bread kneaded, pesto chopped, and whipped cream whisked.

Mahle’s routine starts each weekend. She places orders for the coming week with local purveyors and also looks to see what’s available in her own vegetable, herb, and flower garden. The menu involves a fair amount of strategy. For example, meat cuts come onboard frozen.

“I plan those big roasts and tenderloins and legs of lamb for the end of the week, so they thaw over the course of the trip,” she explained. “The smaller cuts—anything ground or in a stew form—come earlier.”

Everything has its place in the galley’s tight confines, where Mahle and her assistant prepare daily meals for 30 people—without the conveniences of a modern kitchen.

Everything has its place in the galley’s tight confines, where Mahle and her assistant prepare daily meals for 30 people—without the conveniences of a modern kitchen.

Her menus for the week depend on ingredients available from local growers. She enjoys having guests visit the galley, watch production, and weigh in with recipe ideas. But a special moment occurs before dawn every day, when she quietly makes her way to the dark galley—being careful not to wake sleeping guests—to fire up the woodstove and get the old-fashioned drip-pot coffee maker going for that first cup of brew.

That’s also when she embarks on three or four hours of baking, prepping breads, sticky buns, and desserts. It’s okay to cook the pans of goodies under sail, she said. If the boat is heeling, it just might mean that one side of a pan of brownies, for example, is thick and fudgy and the other side thin and crispy.

Another strategic challenge is finding space to store prepped items so they don’t slide around during the day. A typical home cook might have plenty of countertop to spread out bowls and pans. Mahle goes for vertical storage.

“I stack my baking sheets crisscross,” she said. “I stack the bowls, sometime separating them with a little plastic wrap. I’m storing them up rather than horizontally.”

Then the stacks go into the sink, cabinets, lockers, under the stove, or even in the wood bin as the wood comes out to leave space.

The routine involves a fair bit of exercise.

“On one tack, we stow everything on the downwind side,” she said. “As we come about, I or a crew member go below and stack everything again on the down side. We’re up and down all the time.”

In recent years, Mahle shifted dining service from sit-down meals in the galley—with an hour of setting the table and cleaning up each time—to buffets on the deck.

“That freed up three hours every day so we could kick it in terms of the level of food we make,” she said. “Let’s say we’re making gnocchi with a braised pork loin and a vegetable or two. If I’ve got more time, I can glaze some pecans to go on top of the kale, make an extra sauce, and toast some cumin to toss with the tomatillos.”

In a sense, the wind and waves are themselves part of the menu.

“Anybody who’s going to go sailing, and try to eat meals on the boat, has to be flexible and patient with the waves and the wind,” Mahle said. “You are at their whim. Your goal is to mitigate as many disasters as possible. If you accomplish that, then you’ve won.”

✮

MBH&H Contributing Editor Laurie Schreiber is also a Mainebiz staff writer and has covered topics in Maine for more than 30 years.

Tips for the galley chef

Annie Mahle, former co-owner, captain, and chef of the Schooner J. & E. Riggin in Rockland, Maine, has a host of routines she follows to ensure finished dishes make it to hungry mouths and not onto the galley sole. Here are just a few:

■ Plan your menu and ingredients list before leaving shore, but be ready to adapt. Learn how to substitute ingredients, knowing you can’t hop off the boat and run to the grocery store.

■ Optimize galley space by processing as many ingredients as possible before setting off. For example, Mahle receives delivery of whole stalks of edamame. Before leaving the dock, she removes stalks and throws them into the compost bin at the dock, bringing along only the pods.

■ Before setting off, cook down voluminous items such as leafy greens to the extent possible, then store. Cooked greens take up far less space than fresh.

■ Storage might come in surprising spots—lockers, the sink, or the settee.

■ Store vertically, not horizontally. Mahle stacks baking sheets crisscross and stacks bowls, sometimes separated with plastic wrap. She uses stainless steel bowls so there’s no risk of breakage.

■ Store on the downwind side and be prepared to shift your stacks when the boat tacks.

■ Cooking a soup or stew? Don’t fill the pot to the brim. Likewise, for roasts. You don’t want liquid sloshing out. Depending on sea conditions, Mahle fills pots and pans to two-thirds or three-quarters, and roasting pans to half-full.

Mahle’s cookbooks demonstrate how the art of creating delicious food can be accomplished even in tiny spaces—and with no electricity. Here is an easy recipe for fresh salsa.

Pineapple & Orange Bell Pepper Salsa

This bright salsa is delicious with fresh pineapple.

2 cups finely diced fresh pineapple

1 cup finely diced orange bell pepper, about 1 pepper

11⁄2 Tbsp. minced jalapeno pepper

1 Tbsp. minced fresh cilantro

1 Tbsp. extra-virgin olive oil

2 Tbsp. fresh lime juice (~1/2 lime)

pinch kosher salt

Combine all ingredients in a medium bowl. Make up to one hour ahead.

Makes about 3 cups.