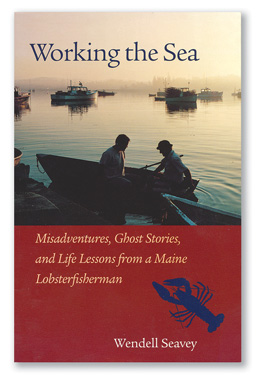

Working the Sea Misadventures, Ghost Stories, and Life Lessons from a Maine Lobsterfisherman By Wendell Seavey North Atlantic Books; Berkeley, California, 2005 275 p., softbound, $15.95 IT IS EASY TO IMAGINE Wendell Seavey regaling a group with his recollections of boyhood, commercial fishing, women, Army life, and experiments living in New Mexico and California, while also imparting uncommon wisdom. Seavey’s stories reveal an intellectual journey and a purpose larger than ego for sharing what he calls his transformation from rough-and-tumble youth to traditional Maine fisherman and environmental advocate. While not every anecdote is compelling, the book is an unselfconscious account of a man curious about life outside his close-knit community. A resident of Mount Desert Island for most of his nearly 70 years, Seavey traces his roots to 1688; when his English ancestors’ early landings on this shore included Seavey Island, now the site of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on the border of Maine and New Hampshire. At 18, he began trawling and longlining with his father, and at one point saved his father from drowning. Decades later, he, too, went overboard and his own son, Wayne, rescued him. He has spent nine adult years on land and forty on the water, and is still counting. “The ocean I knew growing up was teeming with fish and lobsters, whales and seals,” he writes,“and it felt like a very good, natural, rounded world to be in. There was something magical, even spiritual, about taking a line of steam-tarred cotton with steel hooks and a lead weight—dropping it into this frothy ocean that spread to all horizons, so much bigger than the human imagination, and pulling it in and finding it loaded with these huge, amazing creatures.” After five years running his own boat, Seavey joined the Army at 23, completely unprepared for the role of common soldier. Stationed in Hawaii, he had one of his many ghostly premonitions, a vivid dream in which saw his company annihilated under combat conditions. Awake, he was haunted by fear that he likened to what a hunted deer must feel. Although his active duty ended before they were shipped to Southeast Asia, he had “seen” the future of men he knew. “The pace of fishing taught me about the pace of nature,” he writes. “The mechanics of fishing taught me about the ecology I was working in.” Everything led to his “environmental education,” especially conversations with a longtime friend, Father Jim Gower, and Richard Grossinger, an anthropologist who first came to Mount Desert Island in 1969. Grossinger was a long-haired graduate student eager to interview fisherman about their relationship with the natural world. Father Gower figured Seavey could help. Seavey told Grossinger that man is meant to subdue nature.When Grossinger published an article on man’s destruction of our planet, he quoted Seavey as the bad example. Later, Seavey claimed his comment was a lapse, that he supported conservation efforts but thought mankind could and would take charge to prevent global warming and protect the ocean’s bounty. Rather than ignite a war between them, the conflict sparked a decades long dialogue and a friendship cemented by mutual respect. Father Gower also brought another scholar, Ed Kaelber, into Seavey’s kitchen, where over many cups of coffee the men planned a new college whose mission would be to protect and improve the environment. In 1969, College of the Atlantic opened its doors in Bar Harbor, with Kaelber as its first president. In periods when the fisheries declined, Seavey supported his family by working in boatyards, then as activities director at a nearby nursing home, where he discovered a talent for cajoling despondent residents to participate in games and day trips. One year the family tried living in New Mexico, where he developed an educational talk on the life of lobsters that he presented to schools, hospices, and organizations. When he returned to Maine, he adapted the talk for presentations at the Oceanarium in Southwest Harbor. On impulse one day, Seavey drove uninvited to visit Scott and Helen Nearing, considered the founders of modern organic farming. While helping Scott haul wood, he learned first-hand their theories on living off the land.When the Gestalt Institute of Maine opened on Big Duck Island, Seavey ferried therapists and visitors to the island and attended the institute’s workshops on human interaction. Seavey dictated this memoir. An editor’s note says his Downeast diction was converted into standard English rather than “call undue attention to the unconscious linguistic patterns of his subculture at the expense of the story.”Maybe all the readers would have needed was a glossary. After all, storytelling is best sprinkled with local dialect.Regardless, if America sometimes seems to be morphing into homogeneity, it’s good to read books like this by a man who knows his origins.

——Janet Mendelsohn

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

Book Review: Working The Sea

Secondary Title Text

a book by Wendell Seavey

Sections