An Engineless Sailing Adventure

You don’t always end up where you planned

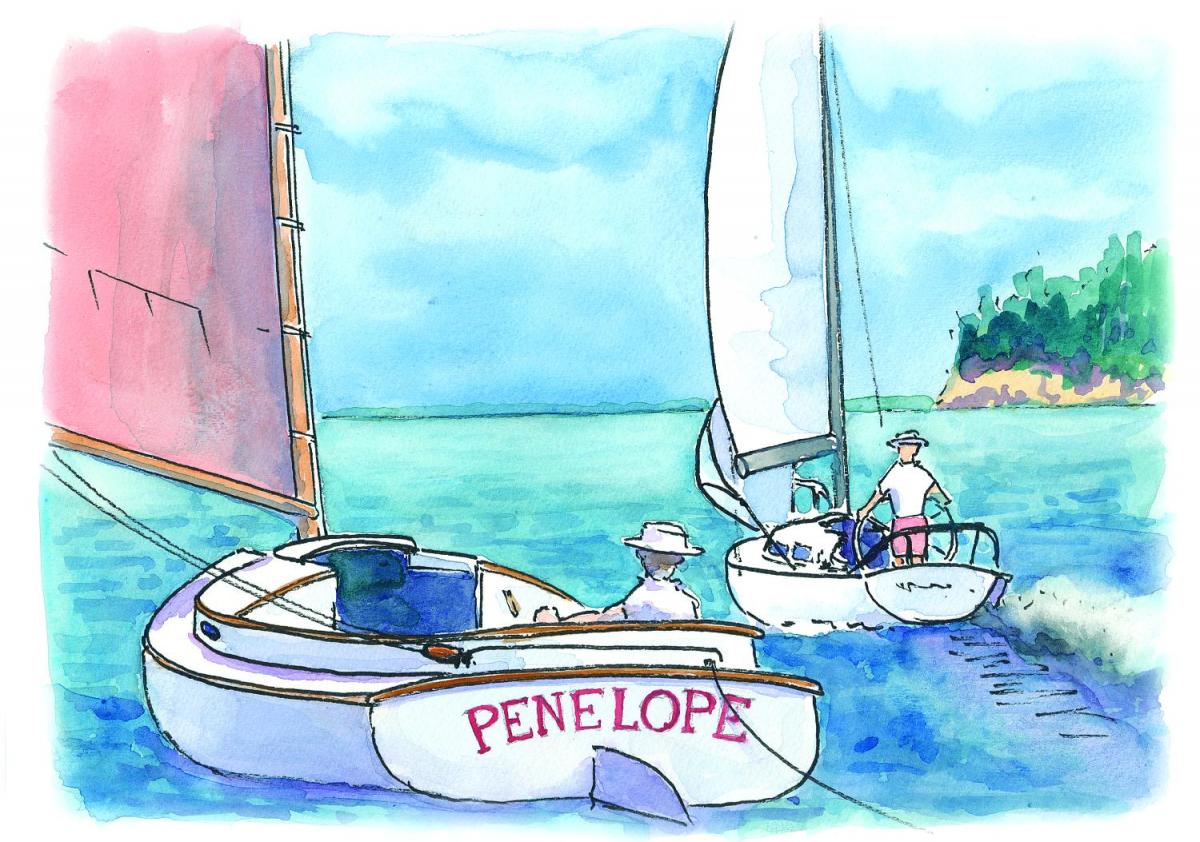

Illustrations by Ted Walsh

It was a bright morning at the WoodenBoat anchorage in Brooklin. I hoped to sail my engineless catboat Penelope west through Eggemoggin Reach, and then as far south as possible toward Pulpit Harbor on North Haven, where I wanted to get oysters from my friend, lobsterman and oyster-farmer, Adam Campbell.

“I spied a whiff of vapor and a spurt of water under his counter. Son of a Gun! The old fraud was motor-sailing.”

“I spied a whiff of vapor and a spurt of water under his counter. Son of a Gun! The old fraud was motor-sailing.”

It was a good plan. Alas, as we neared the western end of the reach the wind fell very light, and then died completely. It was a little before 3 p.m., but we weren’t going much of anywhere. A mile or two to the west lay Orcutt Harbor, and I hoped we could reach it and find shelter for the night ahead.

I kept Penelope pointed west, relying on the unscientific, but surprisingly reliable principle that a sailboat in these conditions tends to proceed in the direction she is pointed, however slowly.

The plan was to sail to Pulpit Harbor on North Haven. But Penelope does not have an engine, and the wind and tide conspired to send her to Castine instead.

Any detectable zephyrs were gone. But although we could not feel anything like wind or a breeze, both Penelope and her tender Argos left subtle wakes, visible as smooth striations of silver and inky black in the mirror-like, glassy water, proof that we were moving over the surface, not just drifting with it.

The plan was to sail to Pulpit Harbor on North Haven. But Penelope does not have an engine, and the wind and tide conspired to send her to Castine instead.

Any detectable zephyrs were gone. But although we could not feel anything like wind or a breeze, both Penelope and her tender Argos left subtle wakes, visible as smooth striations of silver and inky black in the mirror-like, glassy water, proof that we were moving over the surface, not just drifting with it.

We were sailing, although it felt more like being nudged along by an invisible hand.

As time passed my hopes of reaching Orcutt Harbor faded. At our present rate, it would take a long time to get there, and, by then, the current would have started running out of that long narrow gut, making entry problematic. A better bet was Bucks Harbor, a bit back in the other direction, where we might arrive in time to ride the current in.

The trouble with Bucks Harbor, and the reason I had initially passed it by, is that it is so popular and so crowded with boats and moorings that it can be hard to find a spot with swinging room to anchor, especially with no engine.

As we slowly made our way into the harbor, I saw that quite a few of those moorings were unoccupied. While it might not be easy to find a spot to anchor, it was simple enough to grab a vacant mooring. I was delighted to note that the accumulation of weed on the mooring gear indicated that no boat had used it for months. It seemed unlikely that the long-departed owner would choose this particular evening to reappear and kick us off. And, for similar reasons, it would be only moderately irresponsible to leave the boat unattended the next morning while we rowed ashore to visit the town and the local store.

Thus happily situated, I set up my deluxe anti-gravity chair in the cockpit, poured a glass of wine, and pulled out my copy of Taft and Rindlaub’s Cruising Guide to the Maine Coast to check out the features of the harbor and the town of South Brooksville just above.

I was surprised in my reading to find that visiting yachtsmen would not only be welcomed at the local yacht club, but “welcome to use the yacht club’s clay tennis courts and club house.” Such a generous invitation seemed wonderfully old-fashioned.

Arriving the next morning at the club landing I was disconcerted by the “members only” sign. Puzzled, but undeterred, I tied up at the float and went ashore. The tennis courts, which I passed going up the road toward the general store, bore signs proclaiming that they were not only for “members only” but restricted to a special substrata: “tennis members only”. It was here that I began to suspect that my copy of Taft and Rindlaub might be seriously out of date, even though 1991 seems like just yesterday to me.

The town of South Brooksville is quiet, old-fashioned, and totally charming. A kind of sunny stillness lay over the place, and somewhere in the distance I could hear the almost-forgotten whirring sound of an ancient hand-propelled lawn mower.

At the store a long line of customers moved with agonizing slowness past the single register, but I was happy enough to stock up on beer, and delighted to find a box of that special Maine treat, blueberry donuts.

Later, back on Penelope, NOAA predicted moderate breezes from the south or southeast for the next few days, hardly propitious for our intended course southward down East Penobscot Bay toward Pulpit Harbor, especially since the tidal current would be running against us for most of the days immediately ahead.

Well, if you really want to get somewhere, you certainly won’t manage it if you don’t at least try. By noon we were bravely on our way in the face of correctly predicted contrary winds and tide. Penelope sailed southwest along the Cape Rosier shore on one tack. When we reached Blake Point, we fell off and began reaching in a westerly direction toward Head of the Cape.

This was contrary to plan but Penelope and I suddenly found ourselves in a race with a couple of plus or minus 30' sloops headed west. Penelope lives to astound and confound such craft, and seldom passes up a chance to compete. The breeze had picked up to 15 knots or a little over, and had come around more from the east so we were broad reaching at the outer limits of a full sail breeze—conditions that Penelope likes best.

We passed the craft to port easily. The boat coming up behind us to starboard was a different matter. She looked all business, rushing forward with a frothing bone in her teeth, clearly closing the distance between us.

Penelope put up a good fight. I knew we were doing seven to seven and a half knots as I fought the wheel in gusts, but inexorably the big sloop gained, and slowly passed us. I know when I am beaten and doffed my hat in her direction. Her skipper, a natty old boy standing at his destroyer wheel in a white polo shirt and salmon-colored shorts gave us a tolerant nod and then turned his attention resolutely forward, serenely occupied with more important matters.

Then I spied a whiff of vapor and a spurt of water under his counter. Son of a gun! The old fraud was motor-sailing!

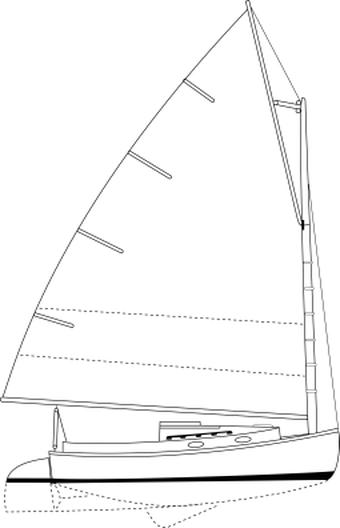

Penelope is a Marshall 22 built by Marshall Marine of South Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Courtesy Marshall Marine

Penelope is a Marshall 22 built by Marshall Marine of South Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Courtesy Marshall Marine

Off to the southwest the pewter-colored sea turned to bright silver where it merged with luminous mist and sky. Sparks of gold flared on wave tops lit by a muted sun glowing palely through the vapor. A shining path lay that way, and we followed it for awhile before, reluctantly, I put the helm over, intending to tack and pass south of Pond Island.

But the breeze, so boisterous just a little while ago, was dropping. Progress in a southerly direction seemed unlikely. It was now after 3 p.m., and time for some serious thought about where to end the day.

The lovely town of Castine lay only a few miles behind us, along the western shore of Cape Rosier, and, most importantly, down wind and down tide. Easy decision; we turned around and headed north.

An hour or so later we arrived in Holbrook Island Harbor, just across the Bagaduce River from Castine, well sheltered, and surrounded by a pristine nature preserve. A sleek loon greeted us with his unearthly cry, and the nearest anchored boat was a half-mile away. We looked forward to a good dinner, and a peaceful evening.

The only trouble with this serendipitous surrender to wind and tide was that in the morning we would find ourselves even farther from Pulpit Harbor than we had been the day before. Ah well, I couldn’t let that bother me too much. Engineless cruising is what it is.

W. R. Cheney is the author of Penelope Down East: Cruising Adventures in an Engineless Catboat Along the World’s Most Beautiful Coast published by Breakaway Books in 2015. He and his wife live in Swan’s Island and South Carolina.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.