A Beachcomber’s Guide to Lobster Gear

A Letter From Matinicus

This rainbow of trash was found in just one day’s walk along the shore. Photo by Eva Murray

This rainbow of trash was found in just one day’s walk along the shore. Photo by Eva Murray

I learned to repair and assemble wooden lobster traps in the early 1980s, in my grandfather’s somewhat dangerous South Thomaston workshop, just before the industry more or less abandoned the use of same. He’d typically purchase a few parts, such as the oak runners, but I remember ripping out laths on the table saw and twisting bait strings out of head twine. Door hinges for wooden traps were cut from old tire sidewalls, and the bricks to weigh them down were just bricks.

When I was 17, I had one string of traps—brand-new, home-built, and heavy—which I hauled from a rowing skiff. This fisheries operation was, obviously to all, a hobby rather than a business, although my license cost just the same. I caught a few lobsters to eat, enjoyed the work, and earned a bit of heckling from the serious guys.

My microscopic lobstering career ended back in the days when you might take a hammer, a few laths, and a pocket full of nails to haul—for any needed minor trap repairs on the go. Back then, “trap nail” was an accepted term in every coastal hardware store. You can’t even buy “trap nails” these days.

Matinicus Island has been my home since I was the teacher here in 1987, and like most middle-aged women on islands, I am a beachcomber. Like everybody else I keep an eye out for the better colors of sea glass, for heart rocks, for the possibility of arrowheads. Like everybody I have assembled a collection of way too many interesting stones, and a regular fortune in sand dollars. I have carried home useful blocking, unbroken bricks, and other stuff too heavy to be at all convenient.

Knots are routinely cut off in the process of working over lobster gear, changing rope, etc. Photo by Eva Murray

Knots are routinely cut off in the process of working over lobster gear, changing rope, etc. Photo by Eva Murray

Mostly, I pick up trash, and most of the trash is plastic. Let’s be honest: we get judgmental about this business. We pick up the litter half-buried in the sand or blown into the Rugosa roses, sure—but we also sputter mightily about the idiot who put it there. Usually, we are justified in such wrath but, I will argue, sometimes we might remind ourselves to calm down.

We can vent our anger about those who shamelessly litter, dump, and pollute on both a large and small scale, but no lobster-catcher wants their traps smashed by storms and carried ashore. When this happens, we holier-than-thou, anti-plastic, rosy-colored-glasses beach-cleanup volunteers need not rise to a height of indignation, because it isn’t the fisherman’s fault. (On the other hand, those tiny little energy drink

bottles, bleach jugs, and cut-off rope knots? Yeah—those are rarely overboard by accident.)

My grandfather went fishing with a round-topped lunch box, which he still called a “dinner pail,” and a one-quart steel Thermos full of his fairly revolting coffee. These days, cold drinks in plastic bottles are the norm aboard the boat, among many other changes from my grandfather’s time that yield disposable remnants. Gallon jugs of bleach are now a routine part of a lobster harvester’s workday, and “pot warp” is now brilliant purple and similar crayon-colored rope. Currently, when fresh bait is in short supply, frozen bait may be used instead; this comes packaged and secured with indestructible plastic strapping bands. Plastic-coated work gloves, often of a bright blue, are as common in beach sand these days as clamshells. When you find those things in the tide pools it’s a good bet some slob aboard a boat was responsible.

But the seaside visitor from way back might ask about some of the other plastic objects wedged in the rocks. A lot of the bits and pieces a 21st-century beachcomber finds aren’t familiar if you haven’t been following recent innovations in lobster gear, and certainly do not fit the traditional image of the old lobster trap you might see in a Winslow Homer painting. The modern lobster trap has a lot of brightly colored, mass-produced plastic add-on parts. Not only are the heads (interior netting) and bait bags now made of brightly colored plastic rather than the old, tan-colored “head twine,” but there is little if any wood left in a typical new trap.

Most lobster traps are adorned with a rainbow of plastic corners, cleats, state-issued identification tags, escape hatches, door hooks, artificial bricks, and perhaps the patented “steady clip.” Tags and the escape hatches, by the way, are not optional. Buoys, especially those used offshore, involve extra parts including long rigid plastic tails and spindles, disc-like plastic spindle washers, spinners for the rope, breakaways and swivels. Styrofoam buoys might be painted with a brilliant substance that costs $100 a gallon, and a rigid plastic buoy is now available if you prefer that to Styrofoam.

I am not going to weigh in on the ethics or necessity of plastic commercial fishing gear parts (although the idea of an artificial brick offers some openings to the wise-alecks among us). It is not my place to opine on whether the plastic parts, in hot pink and a tasteful spectrum of other colors, are essential or not. I also don’t know how much real economic difference they make, but my highliner neighbors wouldn’t be using them if they didn’t help. I would remind the potentially irate beachcomber who takes the time to pick up such detritus that while some fishing-boat trash is a result of a particular, individual mariner’s callousness (any items intentionally jettisoned,) some of it assuredly is not (the stuff that is clearly storm wreckage).

We should also note that local people are not necessarily the culprits when we find trash on any beach. Large ocean gyres and local currents move material around all the time. Beachcombers in Ireland have found remnants of fishing gear from New England and eastern Canada. I found a Canadian tag on Matinicus this past April.

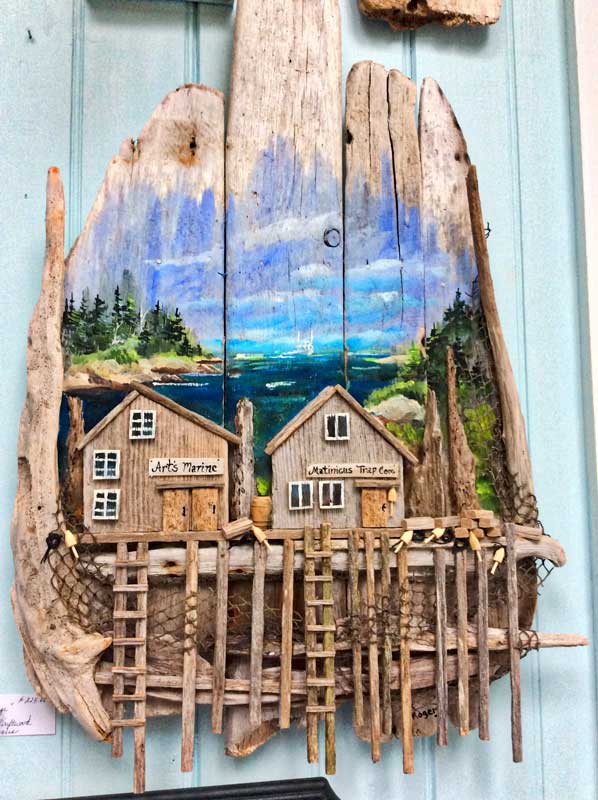

Artist Donna Rogers makes unique three-dimensional pieces from scraps she finds on the beach. Courtesy Donna Rogers

The prettier corners of the planet are advertised as offering “pristine” shorelines. I hate to say it, but there is no such thing as a truly pristine shoreline anywhere in the world. Remote, uninhabited rocks bear the burden of society’s trash. I suspect civilization will be cleaning up beaches from now on, always, and for as long as we have civilization. It’ll be like painting the Golden Gate Bridge—a favorite metaphor for jobs that do not end.

Artist Donna Rogers makes unique three-dimensional pieces from scraps she finds on the beach. Courtesy Donna Rogers

The prettier corners of the planet are advertised as offering “pristine” shorelines. I hate to say it, but there is no such thing as a truly pristine shoreline anywhere in the world. Remote, uninhabited rocks bear the burden of society’s trash. I suspect civilization will be cleaning up beaches from now on, always, and for as long as we have civilization. It’ll be like painting the Golden Gate Bridge—a favorite metaphor for jobs that do not end.

There are a few who might wish the Maine lobster fishery still relied on the old style of gear. Wrecked wooden lobster traps, tossed up on beaches and weathered by salt and surf, sometimes became art supplies for those so inspired. For years, Matinicus Island artist Donna Rogers walked the beaches and carried home bits of weathered laths and scraps of traps to create unique art in her island workshop—and yes, hers is a family of lobster harvesters. If you don’t already have one of Donna’s three-dimensional dockside fantasies on your wall, you’ll soon be out of luck; these days the materials to make them are in increasingly short supply.

Eva Murray lives year-round on Matinicus Island. She has written three books detailing aspects of island life, including Island Schoolhouse: One Room for All (Tilbury House).

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.