Book Review: Sloop

reviewed by Kent Mullikin

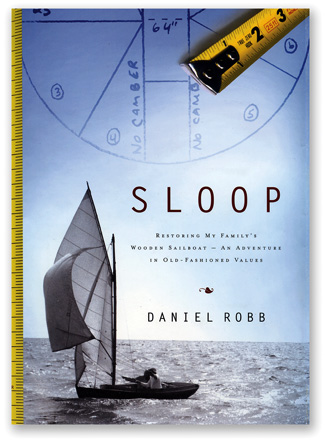

Restoring My Family’s Wooden Sailboat—An Adventure in Old-Fashioned Ideas by Daniel Robb New York, Simon and Schuster, 2008 301 pages, hard cover, $25 Creating a Lasting Impression Fine boats inspire deep passions, and the Herreshoff 12½ is no exception. Designed in 1914 by Nathanael Greene Herreshoff for the breezy waters of Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, the 12½, also known as the Buzzards Bay Boy’s Boat and the Doughdish, is one of the best loved daysailers in America. (12 1/2 refers to the boat's waterline length, not its length overall.) The late Joel White, yacht designer and boatbuilder, called it “probably the best small boat design ever drawn.” Nearly a century after its appearance the 12½ continues to be built and sailed, not only in its original gaff-rigged configuration but also as the Marconi-rigged Bullseye. It is not surprising, therefore, that Daniel Robb was inspired to restore Daphie, the 12½ that had been in his family since 1939 and which had been an important part of his youth in the 1980s. His book Sloop is the story of its restoration—frame by frame, bronze screw by bronze screw—and, as the somewhat portentous subtitle suggests, it is about a number of other things as well: Woods Hole, Buzzards Bay, the Elizabeth Islands, old houses, boatyards, beaches, friends, family, and, ultimately, the author’s view of the world. Pulling all this off may seem a tall order for a man who introduces himself as a house carpenter and seems to take as much pride in his well-worn tool belt as in his other worldly possessions and accomplishments. We learn soon enough, however, that he is also a teacher, an actor, a student of the American past, a descendant of well-off summer folk, and, above all, a writer. Indeed, the initial spur for this restoration project was the thought that there would be a book in it. Once he convinced a publisher of the latter, Robb was, with some trepidation, committed to the job. In the end he turned out a pretty good restoration and a pretty good book. Anyone who has taken on a complex project requiring specialized knowledge can sympathize with the author’s continual anxiety as he faces many demanding tasks for the first time. It starts with building a shed to work in, and escalates though such daunting challenges as removing most of the boat’s frames, finding green quarter-sawn white oak to make new ones, learning how to steam, bend, and fasten the new frames, replacing the canvas on the deck, making new mast hoops, fretting over and dealing with the corroded drifts in the original mahogany transom, and various other details that literally haunt Robb's dreams. The transom, for example, occasioned the following reflection: "I awoke this morning at 3:53 a.m., wandered downstairs, and heated old coffee in my battered white tin mug with the blue rim. I was thinking full bore about the transom, and what I would find when I began to repair it later that day. This made my heart beat faster, half with anticipation, half with dread. That’s what awakened me. The boat at times cajoled and bullied me, even in sleep. That was part of the deal." Before Robb took on the unfamiliar aspects of his self-imposed job of work, he had the good sense to seek advice from those who have already mastered them. Thus, in the book we meet a number of skilled boatbuilders. Bill and Rafe, who were rebuilding a Concordia yawl and aiming to build a Rozinante, are a continuing source of advice and opinion, most of it concerning boats. Giff Hogarth interrupted his work on a cold-molded Herreshoff S-boat to offer practical advice on patching the worrisome transom and reassuringly steered the author towards a workable solution. Other friends and acquaintances helped along the way. I have a few cavils, which might have been addressed by an editor more familiar with boats and the water. The author confidently proclaims that a boat named Capella could not have been a true 12½ because “it was sixteen feet long, six inches longer than Daphie.” It’s not quite that simple. True, the handwritten records of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company list the dimensions of the first hull in 1914 as 15 feet 6 inches on deck; and Yachts by Herreshoff, a company catalogue from the 1930s, says “l.o.a. approx. 15½ ft.” Joel White, however, in Wood, Water, and Light makes it 15 ft. 11 in.; and Maynard Bray in Mystic Seaport Museum Watercraft says 15 ft. 10 in., as do Roger Taylor in his Fourth Book of Good Boats and Diana Esterly in Early One-Design Sailboats. Though there is not perfect agreement on the question, a rather well-informed consensus puts the overall length of the H 12½ closer to 16 ft. than 15½. There are a couple of other imprecisions about the length of boats. Joel White’s centerboard version of the boat, inaccurately labeled a “Haven 15” in Sloop, is actually called a Haven 12½, and its LOA is 16 ft. 0 in. The LOA of the Herreshoff S-class sloop is 27½ ft., and the LWL is 20½ ft., not 25 ft. as claimed in Sloop. Some terminology in Sloop doesn’t quite ring true. Sailors refer to “jam cleats” not “jamb cleats” (though that’s a natural slip for a house carpenter). I wonder whether those bronze fittings on the deck for the jib sheet might properly be called padeyes, eyestraps, or something more nautical than “loops.” Similarly, Robb describes “a bronze loop and pulley that slid back and forth on the bronze traveler bar.” Sailors refer to “blocks,” not “pulleys,” and while I’m not sure how this one is attached to the traveler, I doubt that the correct term is “loop.” And then there’s the redundant “three knots an hour” and that landlubberly term, “nor’easter.” These are small matters, but careful boatbuilders, not to mention writers, ought to get them right. Notwithstanding the aforementioned quibbles, this is an enjoyable book. It is a pleasure to follow the process of bringing a much-loved boat back into commission, and one must admire the doggedness of the author. When at last the seats and floorboards were reinstalled and the hull was caulked and painted, Daphie was launched. The mast was stepped, the sails were bent on, and then she was put on a mooring and pumped through a long night by her attentive owner until her planks swelled and she was ready to return to the waters of Buzzards Bay under sail. The book ends with a couple of evocative sails in Daphie, including an overnight cruise to Penikese Island, a nice reward for author and reader alike. Daniel Robb emerges in the course of the narrative as a competent craftsman with a sense of his own limitations and aspirations. He sensibly drew the line short of perfection and aimed for a structurally sound rather than a museum-quality restoration---and he succeeded. All in all, he put a lot into his wholesome little boat—oak frames, bronze screws, epoxy, effort, care, recollection, and in the end…himself.

—— Kent Mullikin