Visiting Elisabeth

The literary pilgrimage as weather-base

When I set out from Port Clyde by sailboat in thick fog, I wasn’t entirely sure where I was going or what I was looking for. I had been waiting out poor weather for three days and was hoping for a distraction from what had been a dismal stretch of September weather. Then I noticed Gays Island on my chart of Muscongus Bay. It was sneezing distance from my anchorage. A sailing adventure takes a literary turn.

A sailing adventure takes a literary turn.

I had a vague recollection that famed Maine writer Elisabeth Ogilvie had lived on Gays, but I didn’t know if this was the same island. I had asked a curator at the Port Clyde Lighthouse Museum the day before; he had shrugged and told me there were too many Gays Islands in Maine to know for sure. After days of sitting on a small sailboat, I decided I would take my chances.

A literary pilgrimage is not a new notion for me; my childhood vacations were spent packed into the family minivan, driving to the homes of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Lucy Maud Montgomery, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, the Alcotts, and others. In my family, where writers are heralded as clergy in the great religion of the written word, visiting the homes of authors is as much a part of experiencing their work as reading their books. Which is perhaps why, as a small, tidy, white cape appeared on the island that materialized before me, I became increasingly hopeful that I had arrived at the seaside home that bred Elisabeth Ogilvie’s significant collection of work.

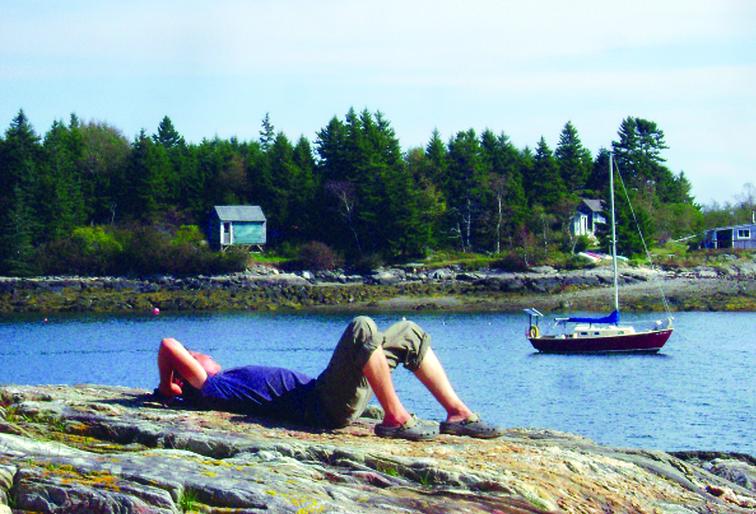

Ogilvie's stories rely heavily on place. Courtesy Robin McCarthy (2)

Ogilvie's stories rely heavily on place. Courtesy Robin McCarthy (2)

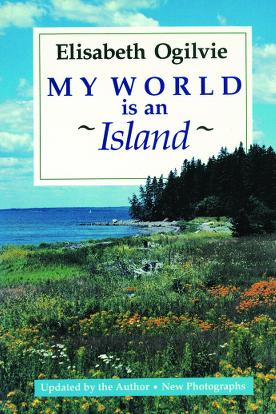

Ogilvie, who summered on Criehaven, and modeled the settings of many of her books on that small island near Matinicus, eventually made Gays Island, just off the town of Cushing, her permanent home. She wrote of Gays in her only work of nonfiction, My World is an Island, in which she told tales of her life there with fellow writer Dorothy Simpson. That book has always struck me as the 1950s literary equivalent of a modern “behind the scenes” documentary: a peek into the life that produced nearly 50 novels over more than 50 years.

Ogilvie began her career in 1944 with the publication of High Tide at Noon, the first in a trilogy of novels offering complete immersion in life on a small Maine island. Like many readers, this was the first book by Ogilvie I read. It was my introduction to Bennett Island, Ogilvie’s fictional version of Criehaven. In it, she describes the place vividly, in a way that not only conveys her characters’ love for the island and its familiar coves and apple orchards, but also sparks longing in the reader.

Longing is exactly what I feel each time I read about Bennett Island; I long for a different place, a different time. I am transformed, carried into the pages of the book and left there, far past the end of a gripping story.

In a way, sailing my small sloop to the site where the Bennett Island books were written was an effort to satisfy that longing, to somehow become a part of the world I had read about. The sight of the little white house at the head of the cove, not-quite concealed by fog, sporting an overall welcoming appearance, was encouragement enough for me to drop anchor in Gays Cove.

“That’s the sort of house she would have lived in,” I thought. “She,” in my wistful imagination, was part Elisabeth Ogilvie and part the heroine of many of her novels: strong, steadfast Joanna Bennett.

Joanna is the coastal Maine version of Jo March (Little Women), Laura Ingalls (Little House on the Prairie), or Anne Shirley (Anne of Green Gables). These impulsive, driven, likable but imperfect women have been the friends I’ve returned to in books since my youth.

But when Elisabeth Ogilvie imagined Joanna Bennett and put her on a fog-covered Maine island, she created a character I identified with more deeply than Jo, Laura, or Anne. Joanna is pushy and stubborn, committed to preserving the way of life on her island home to a fault, often at the expense of her relationships with others. I, too, am an imperfect daughter of the Maine coast, and I, too, have let my passion for this place derail careers and relationships, both by accident and on purpose.

I was in my twenties when I first picked up an Ogilvie novel, but I could have been twelve, for how willingly I fell into the story of a young woman who can overcome countless mistakes to forge a happy life on a vital and unforgiving island. Love, kindness, and the Maine coast conquer all.

I let down the anchor in Gays Cove and coiled the lines. I felt in my heart that the house staring back at me must be the writer’s. Two kayakers paddling by confirmed my suspicions; they said that I had indeed arrived at Elisabeth Ogilvie’s Gays Island. I was overwhelmed—inexplicably shed tears—here clearly was crazy, illogical proof of my deep spiritual connection to Elisabeth Ogilvie.

Later, I landed my punt on the small beach in front of Ogilvie’s house. It was closed up for the coming winter, so I sat on the lawn, taking a moment to imagine her literary life here. This is what you do on a literary pilgrimage: you sit where the work was written, you imagine the desk, the paper, the pen, perhaps a typewriter, a cup of tea. You imagine animals running through the yard, settling at the writer’s feet, the writer filling a blank page with words that will be read, voraciously, by enthusiastic readers, for generations.

Soon I was no longer imagining Ogilvie in her home, but inserting myself as the primary resident of this perfect cape. Resisting the urge to peek through the windows, I indulged my fantasy while following the island’s footpaths. I wondered if the house might be for sale, if I could afford it on my fledgling writer’s income. I imagined where I would buy groceries on the mainland between long uninterrupted stretches of time on the island. I wondered if I would need to keep a car in Cushing or if the sailboat would be vehicle enough.

I did not break free from the daydream until later, when there was just a hundred yards of water between me and the island. I was watching the sun set from the deck of my boat when I was struck with an embarrassed sadness as I began to see that this was not my home, or my island. This was not my life, and it wasn’t wholly Ogilvie’s any more, either.

I grew up spending my summers on a Maine island not all that different from Gays. On my island, our celebrated Maine author was Ruth Moore, whose home rested on a hill just above our house. By the time I was born, Moore had long moved ashore and had a career on the mainland; the Moore family had sold the house to a family of summer visitors. I grew up playing in the Moore’s old barn, which provided endless opportunities for imaginary games. My memories of that house, however, have nothing to do with the resident who made it notable, but with the children and friends who have lived there since.

As I watched from Gays Cove, the white clapboards of Ogilvie’s cape reflected the pink and orange sunset. A different family lives in the house now. For them, the stories of their home have little to do with Elisabeth Ogilvie or Joanna Bennett. Rather, Ogilvie is just one part of the house’s history, a note scrawled in the margin. Their stories involve a whole new cast of characters, fresh generations of children growing up on a Maine island.

That week I was re-reading Sarah Orne Jewett’s Country of the Pointed Firs. I read the final pages of the book on the bow of my sailboat by the last moments of daylight. I thought about the Maine women writers who had visited me in one way or another throughout the day. I marveled at how Maine’s land and people have inspired such a uniquely wonderful collection of books for generations. I had originally set out by sail to explore the coastal geography of my native state, but here I was, steeped in a literary tradition I hadn’t expected to find.

Elisabeth Ogilvie’s stories, like those of Ruth Moore, Dorothy Simpson, Sarah Orne Jewett, and countless others, rely heavily on place, on settings along the coast of Maine. They have become as natural a part of the Maine coastline as cormorants and harbor seals. Like steadfast lighthouses in the fog, these stories mark a place and a time to remember, an essential part of being here.

Robin McCarthy now sails on Swallow, an Allied Seawind II, which is usually moored in the harbor at Belfast, Maine. Mama Tried, the vessel used for this adventure, has been put on the market.

More information

Elisabeth Ogilvie’s My World is an Island was published in 1950 by Down East Books, Rockport (www.downeast.com) and is widely available.