Dr. Gould’s Flying Nurses

Homing pigeons helped him stay in touch with his patients

A photo of Dr. Edwin Gould in Representative Men of Maine: A Collection of Portraits of Residents of the State Who Have Achieved Success, edited by Henry Chase, Lakeside Press, 1893.

Dr. Edwin Gould, a physician practicing out of Rockland at the turn of the 20th century, had none of the high-tech communications devices available to people living on Penobscot Bay islands today. No telemedicine, no airplane, no iPhone, not even a landline. What Gould did have was a very low-tech but inspired solution to communicating with islanders—homing pigeons.

A photo of Dr. Edwin Gould in Representative Men of Maine: A Collection of Portraits of Residents of the State Who Have Achieved Success, edited by Henry Chase, Lakeside Press, 1893.

Dr. Edwin Gould, a physician practicing out of Rockland at the turn of the 20th century, had none of the high-tech communications devices available to people living on Penobscot Bay islands today. No telemedicine, no airplane, no iPhone, not even a landline. What Gould did have was a very low-tech but inspired solution to communicating with islanders—homing pigeons.

Born in 1854 in North Bucksport, Edwin W. Gould began his working career as a traveling salesman for the New England Organ Company of Boston. Although he did well selling musical instruments, his real goal was a career in medicine. That essential tome, Gray’s Anatomy, traveled with Gould wherever he went, and he studied during every free moment. According to a profile of Gould that appeared in the 1893 edition of Representative Men of Maine, he entered Bowdoin College’s Medical Department in 1885, and graduated in 1887. He first practiced medicine in Swanville and Searsport, Maine. In 1893 he moved to Thomaston, and finally, to Rockland, where he set up an office on School Street.

While helping citizens of Rockland, Dr. Gould also cared for patients on two remote Penobscot Bay islands, Matinicus and Criehaven, which were inhabited at the time by about 200 people.

Criehaven, shown here in 1900, was at one time an active fishing and farming community. In addition to healthcare, Dr. Gould’s pigeons were used to place orders for goods. A 1901 newspaper article mentions an order from the island for iron being placed at the H.H. Crie and Co.’s Rockland store via pigeon. “This service can be made very valuable and Dr. Gould intends to improve it,” the newspaper reported. Eventually the 440-acre Penobscot Bay island lost its school, post office, and general store. Today Criehaven has few if any year-round residents. Courtesy Rockland Historical Society, Ida Crie Collection

Criehaven, shown here in 1900, was at one time an active fishing and farming community. In addition to healthcare, Dr. Gould’s pigeons were used to place orders for goods. A 1901 newspaper article mentions an order from the island for iron being placed at the H.H. Crie and Co.’s Rockland store via pigeon. “This service can be made very valuable and Dr. Gould intends to improve it,” the newspaper reported. Eventually the 440-acre Penobscot Bay island lost its school, post office, and general store. Today Criehaven has few if any year-round residents. Courtesy Rockland Historical Society, Ida Crie Collection

Prior to radio and telephone, many lighthouses used homing pigeons for communication, including Boon Island Light, off Maine’s southern coast. Also, the Star Island Oceanic Hotel, in the Isles of Shoals off New Hampshire, whose pigeons are shown here, used the birds in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to hotel guests, lunch was available for day-trippers, but to calculate how many meals to prepare each day, the island-based chefs needed an incoming head count. Each day, pigeons were sent into Portsmouth, N.H., on an early morning boat. When the return boat left the harbor, a hotel employee wrote the number of visitors on board on a slip of paper, put it in a canister on one of the pigeon’s legs, and let the bird go. The birds became celebrities and remained in service even after a telephone was installed at the hotel. Photograph courtesy Star Island Corporation

In A Mug-up With Elisabeth, authors Melissa Hayes and Marilyn Westervelt describe the early history and settlement of Criehaven, which under the control of Robert Crie grew into a self-governing community. In 1848, Crie, who was living on Matinicus, bought what was then called Ragged Island. With his wife, Harriet Hall, he built a homestead there and became a prosperous fisherman and farmer. He also ran the general store and post office, and opened a school, soon solidifying his position as the backbone of the thriving island community. He incorporated the island as the plantation of Criehaven in 1896.

Prior to radio and telephone, many lighthouses used homing pigeons for communication, including Boon Island Light, off Maine’s southern coast. Also, the Star Island Oceanic Hotel, in the Isles of Shoals off New Hampshire, whose pigeons are shown here, used the birds in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to hotel guests, lunch was available for day-trippers, but to calculate how many meals to prepare each day, the island-based chefs needed an incoming head count. Each day, pigeons were sent into Portsmouth, N.H., on an early morning boat. When the return boat left the harbor, a hotel employee wrote the number of visitors on board on a slip of paper, put it in a canister on one of the pigeon’s legs, and let the bird go. The birds became celebrities and remained in service even after a telephone was installed at the hotel. Photograph courtesy Star Island Corporation

In A Mug-up With Elisabeth, authors Melissa Hayes and Marilyn Westervelt describe the early history and settlement of Criehaven, which under the control of Robert Crie grew into a self-governing community. In 1848, Crie, who was living on Matinicus, bought what was then called Ragged Island. With his wife, Harriet Hall, he built a homestead there and became a prosperous fisherman and farmer. He also ran the general store and post office, and opened a school, soon solidifying his position as the backbone of the thriving island community. He incorporated the island as the plantation of Criehaven in 1896.

At that time, boats provided the only means of contact between island communities and the mainland, including fetching a doctor. When Dr. Gould set up his practice, steamers had replaced many of the schooners and other sailing vessels that ferried people and supplies back and forth. Still, a successful trip depended on the erratic weather. Gale-force winds commonly blew for several days, or unremitting fog shrouded the islands. Often, Dr. Gould simply couldn’t reach the islands, or found himself stranded on one for weeks.

Photograph courtesy Star Island Corporation

What he referred to as his “flying nurses” dramatically changed his practice. When he boarded a steamer for Matincus or Criehaven, he’d carry a crate of sleek homing pigeons along with his doctor’s bag. Before he returned to the mainland, he’d leave several birds with the patient’s family, with instructions on how to care for them and how to release them with a message.

Photograph courtesy Star Island Corporation

What he referred to as his “flying nurses” dramatically changed his practice. When he boarded a steamer for Matincus or Criehaven, he’d carry a crate of sleek homing pigeons along with his doctor’s bag. Before he returned to the mainland, he’d leave several birds with the patient’s family, with instructions on how to care for them and how to release them with a message.

A 1901 New York Times article about Gould’s pigeons explained that on a good day, a homer could cross the 20 miles of ocean to Gould’s loft in Tenants Harbor in just 40 minutes. An assistant at the loft then relayed the message via telephone to Gould at his office in Rockland, and he would decide whether another trip was needed or not. With his pigeon messenger system in place, Dr. Gould could maintain a working office in Rockland while still serving the islands. His novel method of communication became known worldwide, with enthusiastic letters and inquiries coming from as far away as New Zealand.

Robert Crie (1826-1901), known as “King Crie” for his role in buying the island of Criehaven and incorporating it, is shown here in his wheelchair in 1900. Courtesy Rockland Historical Society, Ida Crie Collection

Why Dr. Gould decided to try out a pigeon post is not known. He may have heard of light keeper William C. Williams’ use of the birds to carry messages between Boon Island and the mainland in southern Maine in the 1890s. Or, he might have read about pigeon messenger services used by other physicians. Dr. Philip Arnold, a physician in Elizabeth, Illinois, and Dr. Charles Lang, who worked in Meriden, New York, both used homing pigeons to bring news from rural patients to their offices. In the late 1880s and 1890s, their articles and letters extolling the virtues of homing pigeons as medical messengers appeared in prestigious medical journals, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association and the Medical Review. Perhaps Dr. Gould had read the articles and realized the potential of such a system for his island practice.

Robert Crie (1826-1901), known as “King Crie” for his role in buying the island of Criehaven and incorporating it, is shown here in his wheelchair in 1900. Courtesy Rockland Historical Society, Ida Crie Collection

Why Dr. Gould decided to try out a pigeon post is not known. He may have heard of light keeper William C. Williams’ use of the birds to carry messages between Boon Island and the mainland in southern Maine in the 1890s. Or, he might have read about pigeon messenger services used by other physicians. Dr. Philip Arnold, a physician in Elizabeth, Illinois, and Dr. Charles Lang, who worked in Meriden, New York, both used homing pigeons to bring news from rural patients to their offices. In the late 1880s and 1890s, their articles and letters extolling the virtues of homing pigeons as medical messengers appeared in prestigious medical journals, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association and the Medical Review. Perhaps Dr. Gould had read the articles and realized the potential of such a system for his island practice.

However, unlike Arnold’s and Lang’s land-based situations, Gould faced the extra challenge of convincing his birds to fly over long stretches of water—something pigeons don’t care to do. By the late 1890s, though, Dr. Gould would have had access to well-trained birds provided by experienced keepers. By then, fanciers had established racing clubs in America and organized races up and down the East Coast. Birds were not only trained to race hundreds of miles, they were trained to fly over water. The U.S. Navy had also been experimenting with a pigeon messenger service, and had many successes in releasing birds from ships at sea to shore lofts, sometimes more than 100 miles away.

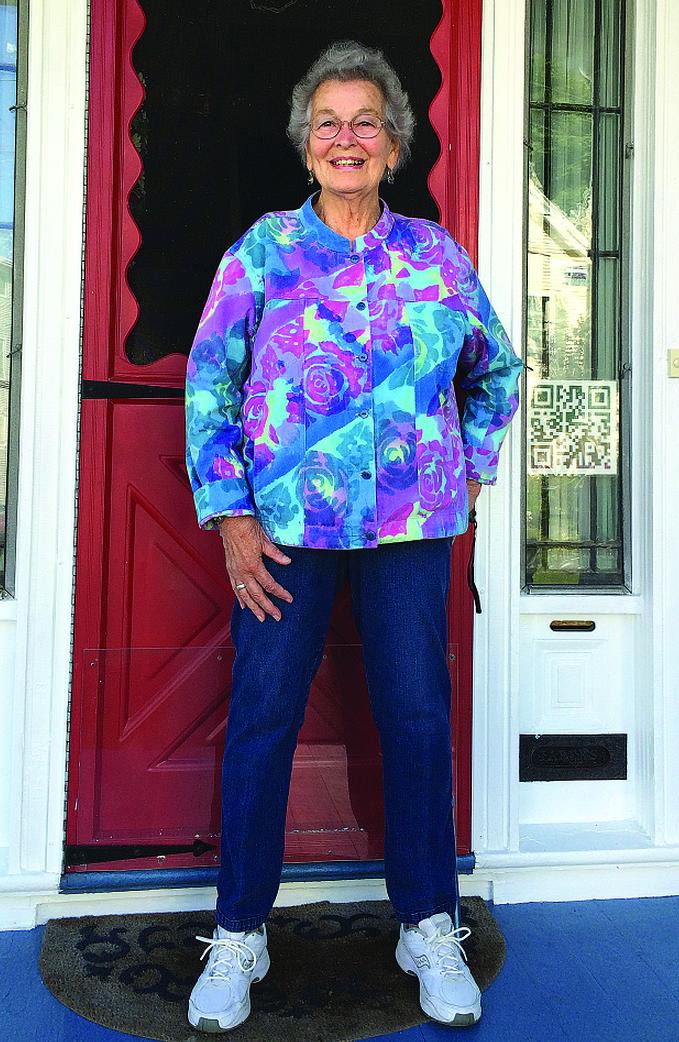

Today, Crie descendent Celia Crie Perry owns Dr. Gould’s former home in Rockland, which has the remnants of an old pigeon coop in the barn. Called “Crie Haven,” the home is now run as a Christian retreat.

With attentive care and consistent training, homing pigeons will fly over open water and through just about any kind of weather to reach home. Even after breaking a wing, they’ve been known to walk the rest of the way to their loft. Besides their extreme athleticism—they rank among the fastest birds, with endurance to match, scientists believe they use a combination of extraordinary eyesight and hearing, plus a kind of internal magnetic compass to navigate. There is no other creature as unflinching and tenacious in an effort to reach its home.

Today, Crie descendent Celia Crie Perry owns Dr. Gould’s former home in Rockland, which has the remnants of an old pigeon coop in the barn. Called “Crie Haven,” the home is now run as a Christian retreat.

With attentive care and consistent training, homing pigeons will fly over open water and through just about any kind of weather to reach home. Even after breaking a wing, they’ve been known to walk the rest of the way to their loft. Besides their extreme athleticism—they rank among the fastest birds, with endurance to match, scientists believe they use a combination of extraordinary eyesight and hearing, plus a kind of internal magnetic compass to navigate. There is no other creature as unflinching and tenacious in an effort to reach its home.

One day in June of 1901, such a bird fought its way through a storm to carry news of the utmost importance from Criehaven to the mainland. Earlier, Dr. Gould had tended to the ailing, 75-year-old Robert Crie and left a few birds with Horatio, Crie’s son. All of Rockland awaited news of the distinguished citizen’s condition. For several days a storm had raged, making the seas impossible to navigate. On June 25, Crie’s family fastened a tiny slip of paper to a sturdy pigeon, and Horatio lifted the bird into the fierce winds blowing across Criehaven. Just one hour later, the weary pigeon landed at its loft in Tenants Harbor, the news of Robert Crie’s death safely attached to its leg.

One of Dr. Gould’s flying nurses had delivered a critical bulletin that might otherwise have taken days to reach him. His pigeons remained an essential part of his island practice for several years, serving not only as couriers of symptoms and outcomes, but also as lifelines between remote families and their doctor.

Elizabeth Macalaster lives in Brunswick, Maine, and part time in Friendship, Maine. She is working on a book about the role of homing pigeons in the U.S. Navy, and she’s also written a wilderness thriller, Reckoning At Harts Pass, in which homing pigeons appear.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.