Answering Lubec’s Fish Whistles

Recollections of the sardine glory days

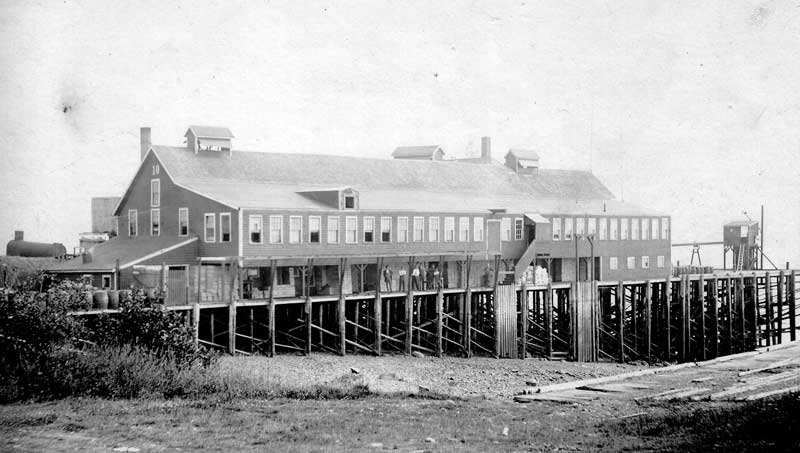

By 1950, Maine was home to 70 sardine factories, including 23 in Lubec. The factories operated from Kittery to Eastport, employing 6,000 workers of both genders in the state’s largest industry. Photo courtesy St. Croix Historical Society

By 1950, Maine was home to 70 sardine factories, including 23 in Lubec. The factories operated from Kittery to Eastport, employing 6,000 workers of both genders in the state’s largest industry. Photo courtesy St. Croix Historical Society

Bernie Porter, now 72, began working in Lubec’s sardine industry as a 10-year-old in 1955. Photo by Ron Josesph

Bernie Porter tried to leave Maine, but it didn’t work. He got a job as a pipe fitter in Boston in 1963, when he was 18 years old. Four months later, he was back home in Lubec, and back at work in the sardine industry.

Bernie Porter, now 72, began working in Lubec’s sardine industry as a 10-year-old in 1955. Photo by Ron Josesph

Bernie Porter tried to leave Maine, but it didn’t work. He got a job as a pipe fitter in Boston in 1963, when he was 18 years old. Four months later, he was back home in Lubec, and back at work in the sardine industry.

Life taught Porter, one of 14 children, to be resourceful. On his return to Lubec, he landed a job in a herring smokehouse. “One day I was a pipe fitter and a few days later I was a ‘herring choker,’” said Porter, now 72. That’s the name given to smokehouse workers who string herring on 42-inch sticks through the fish’s gills and mouth. “I’d slide a fish onto a stick and then add more until 22 to 28 herring were threaded,” he explained.

He’d hang the full sticks of herring on two-by-fours in a smokehouse (the first racks of sticks were about seven feet above the fire) and repeat the procedure until fish were hanging all the way up to the roof. Smoke from burning saltwater driftwood coated the drying fish. To increase smoke and decrease heat, Porter shoveled sawdust onto the embers. After five days, the smoked herring were cured and edible.

While the glory days of the sardine industry in Maine ended long ago, people like Porter still remember when herring fueled the local economy.

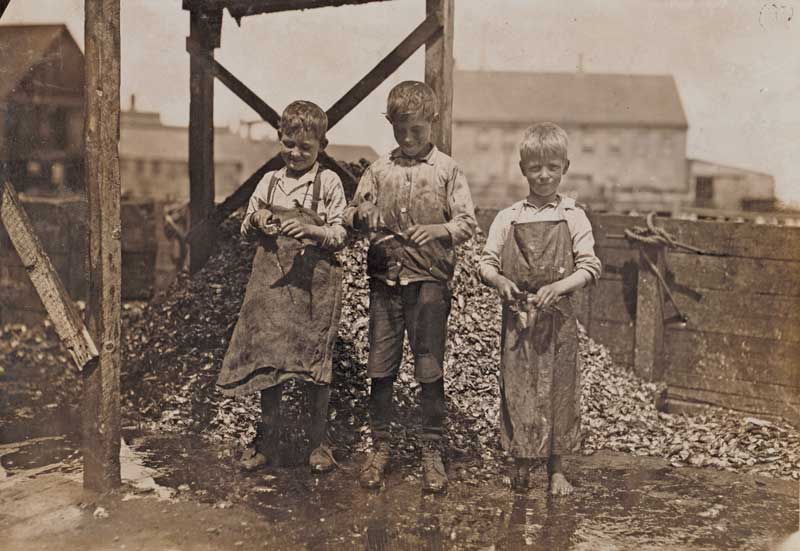

Lewis Hines, who documented working conditions in Maine sardine canneries in 1911 for the National Child Labor Committee, took this photo of three boys, ages 6, 7, and 9, working as cutters at a Seacoast Canning plant in Eastport. The boy on the left with the cut and bandaged finger told Hines that the salt from the herrings got into the cut and hurt, and that some days he earned $1.50. (Above) Photo courtesy Library of Congress, National Child Labor Committee Collection

Lewis Hines, who documented working conditions in Maine sardine canneries in 1911 for the National Child Labor Committee, took this photo of three boys, ages 6, 7, and 9, working as cutters at a Seacoast Canning plant in Eastport. The boy on the left with the cut and bandaged finger told Hines that the salt from the herrings got into the cut and hurt, and that some days he earned $1.50. (Above) Photo courtesy Library of Congress, National Child Labor Committee Collection

Lubec’s first commercial herring smokehouse opened in 1797. Smoking the seasonally abundant fish was the only method of preserving a food source for year-round consumption. The industry peaked in the mid-1800s when 30 Lubec smokehouses annually produced 500,000 10-pound boxes of smoked herring. By 1855, Lubec produced more smoked herring than any fishing community in the United States and the town’s economy was booming.

“Old-timers told me the need for workers was so great, smokehouses employed every Lubec male resident age 10 and up,” said Porter. “Lubec’s smoked herring were shipped in shooks (wooden boxes) to ports around the world.”

Sardine canneries came on the scene later, in the 1870s. The 1940s and 1950s were the golden years of sardine production in Maine, with 70 operating sardine canneries. It was the state’s largest industry, employing more than 6,000 workers at one point, according to Ron Peabody, director of the Maine Coast Sardine History Museum in Jonesport. At one time, Lubec alone had 23 operating sardine factories.

Ancillary businesses sprang up. Loggers cut pine logs, which sawmills made into boards. Specialty mills turned the boards into shooks. Shipbuilding companies employed hundreds of craftsmen to make herring fishing vessels. “If you sailed the coast of Maine in 1950,” Peabody said, “you’d have seen sardine canneries from Kittery to Eastport.”

Today herring are used mostly as lobster bait. The state’s last herring smokehouse closed in 1990 and the last cannery—located in Prospect Harbor—closed its doors in 2010.

Porter was 10 years old in 1955 when he got his first smokehouse job. The Columbian Company Smokehouse paid him a penny for each stick of 22 to 28 herring. The work was dangerous, he said.

“My friend Mickey fell 40 feet to his death. He was standing on a plank near the smokehouse roof, rotating sticks of herring to ensure an even cure. The building was smoky and Mickey’s plank broke,” said Porter. “I watched him fall, breaking sticks of herring below him until he landed on the bottom of the smokehouse. No 10-year-old should witness such a horrific accident.”

Accidental cuts also were common. Porter’s niece cut off the tips of three fingers while skinning a smoked herring with sharp scissors.

A man named Raymond “Skunks” Braggs sharpened scissors and knives for the fish-plant workers. “His nickname derived from his pitch-black hair with streaks of gray. It resembled a skunk’s pelt. If Skunks liked you, he’d sharpen your tools and they’d keep an edge for six months or longer,” said Porter. “If he didn’t like you, your cutting tools would be dull in less than a week.”

Skunks dabbled as an eccentric artist. He collected beach trash deposited by high tides and fashioned it into art. In the 1980s, he set up a table on Lubec’s Main Street to sell sea-glass trinkets to tourists, but few people stopped to buy anything. “Then one morning he arrived at his roadside table wearing a woman’s wig, a dress, make-up, leggings, and carrying a purse. By mid-afternoon, every item had been sold,” Porter said. “Skunks was unconventional, but he made a lot of money that summer selling his art.”

Porter’s mother before him also started working when she was 10—in 1916. She held that job of sardine packer until age 47, when she was diagnosed with cancer. “My mom had a very difficult life,” Porter said. “She struggled to earn enough money to feed and dress us kids. After her death, we owed her employer $17 for food she’d purchased for us from the sardine company store.”

As demand for canned sardines increased in the 1940s, Porter’s mother worked for three canneries at the same time. That was possible because sardine carriers staggered their factory deliveries. She was paid piecemeal, earning 10 cents for every 100 packed cans. “I nicknamed her ‘Lightning,’” Porter said. “Her hands were a blur packing sardines. The more cans she packed, the more money she made.”

Men trapped and collected herring in weirs, transported the fish by boat to the factories, and operated pressure cookers to sterilize canned sardines. But women comprised the bulk of the sardine cannery workforce, according to Peabody, removing sardine heads and tails with knives and scissors before packing the fish in cans. Women often operated the can sealers and packed shooks with cans of sardines for shipment as well.

Christine Brown was a sardine worker during WW II, when thousands of cases of Lubec canned sardines were shipped to Americans fighting in Europe and the South Pacific. Photo by Ron Josesph

Christine “Teeny” Brown was a member of that workforce. Now 97-years-old, the slender, sharp-minded Brown was a seasonal sardine packer from 1932 until 1962, starting during the Depression when she was 13. Her mother, also a sardine packer, got her the job—back then entire families, including children, worked in the canneries. That ended in 1938 when a federal child labor law was enacted.

Christine Brown was a sardine worker during WW II, when thousands of cases of Lubec canned sardines were shipped to Americans fighting in Europe and the South Pacific. Photo by Ron Josesph

Christine “Teeny” Brown was a member of that workforce. Now 97-years-old, the slender, sharp-minded Brown was a seasonal sardine packer from 1932 until 1962, starting during the Depression when she was 13. Her mother, also a sardine packer, got her the job—back then entire families, including children, worked in the canneries. That ended in 1938 when a federal child labor law was enacted.

“My father was floor boss in the Seaboard Cannery where I worked,” Brown recounted, “and he taught me and the other children how to properly wrap tape on our fingers to minimize accidental cuts.”

Seasonal workers came to Lubec from Campobello, Grand Manan, Deer Island, Whiting, and other nearby communities. They lived in rows of sardine company houses and shopped in company stores. “For those folks, it was hard to save money because they had to pay rent and buy food from the company,” Brown said. “I was lucky because I lived at home with my parents.”

The canneries would open when the large schools of herring reached local waters in May and close when the fish disappeared in November. She said, “I didn’t get rich earning a dollar a day, but it was a good summer job.”

Winter was especially hard for the unemployed and homeless, who traveled like gypsies looking for work. In November and December, many laid-off sardine packers worked cutting fir tips and making Christmas wreaths for wholesalers.

Raye’s Mustard Mill in Eastport supplied mustard for flavoring. “To this day,” Brown said, “I hate the smell of mustard. One day, a sloppy girl behind me lost control of a ladle full of mustard. It landed on me and I worked with wet mustard on my back until noontime when I walked home for a change of clothes and lunch.”

Men, women, and boys processing herring, cutting off the heads and tails at Wolf’s Cannery in Eastport (1882). (Right) Penobscot Marine Museum/Boutilier Collection

Cannery workers got a 30-minute lunch break, said Brown. She recalled the story of a pregnant packer named Angelina who worked into her ninth month. “One day Angelina began walking home for lunch but stopped in a field and gave birth,” Brown said. “Her husband came running to her side. He wrapped the baby in a blanket and took it home in a wheelbarrow. Angelina returned to the cannery 15 minutes late and resumed packing sardines.”

Men, women, and boys processing herring, cutting off the heads and tails at Wolf’s Cannery in Eastport (1882). (Right) Penobscot Marine Museum/Boutilier Collection

Cannery workers got a 30-minute lunch break, said Brown. She recalled the story of a pregnant packer named Angelina who worked into her ninth month. “One day Angelina began walking home for lunch but stopped in a field and gave birth,” Brown said. “Her husband came running to her side. He wrapped the baby in a blanket and took it home in a wheelbarrow. Angelina returned to the cannery 15 minutes late and resumed packing sardines.”

Fish-plant workers, like Angelina, took pride in being dependable. Porter recalled a man name Walter Small who worked well into his 80s. During the canning season, Small walked six miles from his North Lubec home to Lawrence’s Sardine Factory. When he turned 85, he left home for work a half-hour earlier. “When Walter reached Morton’s Corner—halfway to work—he unrolled a blanket and took a 30-minute nap in a field,” said Porter. “He’d wake up refreshed, roll up his blanket, and resume walking to the cannery.”

All Lubec residents, whether they worked in a cannery or not, understood the message of the fish whistle. “One whistle meant that the sardine carriers were delivering fish to the canneries,” Brown said. “That meant I had about one hour to get ready for work.”

This photo from an October 1924 issue of Atlantic Fisherman, shows men preparing “Herrin’ hosses” for the smokehouse. Each horse held 45 sticks; and each stick, from 25 to 35 herring. Back in the day bars were a major market for salt smoked herring. Penobscot Marine Museum/Atlantic Fisherman Collection

This photo from an October 1924 issue of Atlantic Fisherman, shows men preparing “Herrin’ hosses” for the smokehouse. Each horse held 45 sticks; and each stick, from 25 to 35 herring. Back in the day bars were a major market for salt smoked herring. Penobscot Marine Museum/Atlantic Fisherman Collection

Three whistles notified packers to report to work because the sardines were ready to be canned. About an hour later, the whistle blew five times, which meant the can sealers needed to return to work, she explained.

World War II revitalized the sardine industry, said Brown. To meet U.S. Army and Navy sardine contract orders, seven new canneries were built in Lubec. “As a 25-year-old during WWII, I remember my hometown as vibrant and beautiful. Everyone was happy with jobs, everyone shopped on Main Street on Friday nights and Saturdays, and on Sunday all four churches were full.”

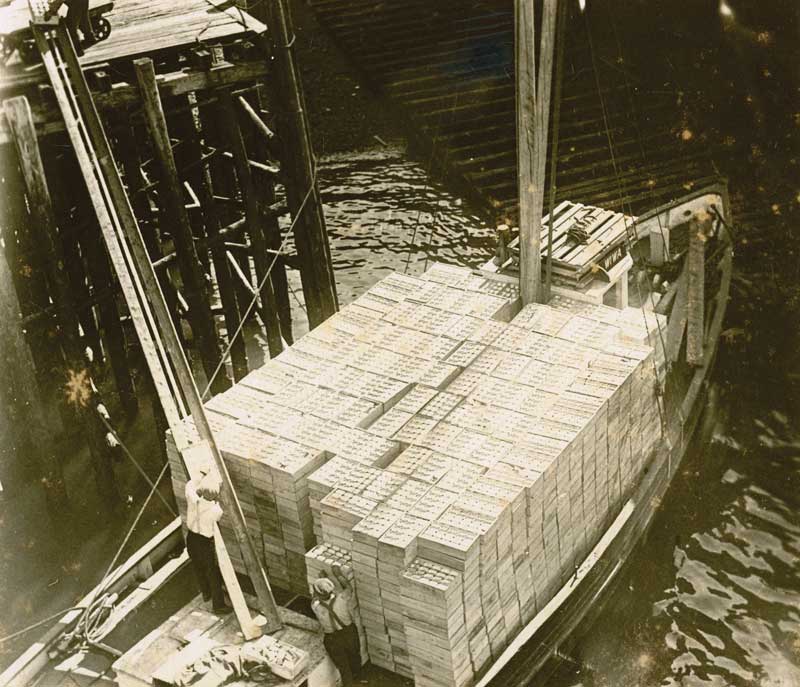

Wooden cases of sardines stacked on a boat ready for transport, circa 1925. Penobscot Marine Museum/Atlantic Fisherman Collection

Wooden cases of sardines stacked on a boat ready for transport, circa 1925. Penobscot Marine Museum/Atlantic Fisherman Collection

One day in 1944, as hundreds of sardine cases were packed in crates for shipment to U.S. soldiers in Europe, Brown and her girlfriends wrote short letters to servicemen and buried them in the crates, hoping to lift the soldiers’ spirits.

“Our name and address was on each letter, and some girls included photos of themselves,” Brown said. She heard after the war from a young Air Force pilot in Pennsylvania who had carried her note while flying bombing missions against the Germans in Europe. “He wanted to visit me in Maine and possibly marry me. But right after the war, I had married and had a baby. So that’s what I wrote to him in a second letter.”

During and after the war, Lubec continued to prosper. “Our education system was renowned statewide. In fact, a higher percentage of our high school graduates attended college than from any other high school in Maine,” boasted Brown. “We were very proud of that accomplishment.”

The era of economic prosperity ended in the 1970s with the closure of American Can Company and all but two of the town’s sardine factories. By 1975, McCurdy Smokehouse was the country’s only remaining smoked herring producer. It’s now a museum. Connor Brothers Company, owners of the last functioning factory in Lubec, closed in September of 2001.

The ripple effect of plant closures and job losses took its toll as long-standing businesses closed and the town’s population declined. Lubec High School, once the pride of town, closed in 2010 with only 40 students enrolled in grades 8 to 12. The town’s population has dropped from 3,300 in 1920 to 1,400 today.

Why the decline? According to Brown, factors included fewer herring, not enough workers, foreign competition, and a new generation that didn’t grow up lunching on sardines.

“It’s true that the work was dirty, noisy, and smelly—we got used to it—but the wages were decent. Work was there for whoever needed it. We women used to have a good time in the canneries. It was hard work, but we all knew one another; we were like a big family. I loved every minute of it. If I could go back and start life over, I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Freelance writer Ron Joseph of Waterville is a retired Maine wildlife biologist.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.