Judy Taylor

Portrait and landscape painter, muralist, and teacher

In response to the pandemic, Taylor joined the Dojo Atelier in Austin, Texas, to paint from the model in live-streaming sessions. Left: Machelle, oil, April 2020, 16 by 12 in. Private collection. Right: Amy, oil, February 2020, 12 by 16 in. Photos courtesy Judy Taylor

In response to the pandemic, Taylor joined the Dojo Atelier in Austin, Texas, to paint from the model in live-streaming sessions. Left: Machelle, oil, April 2020, 16 by 12 in. Private collection. Right: Amy, oil, February 2020, 12 by 16 in. Photos courtesy Judy Taylor

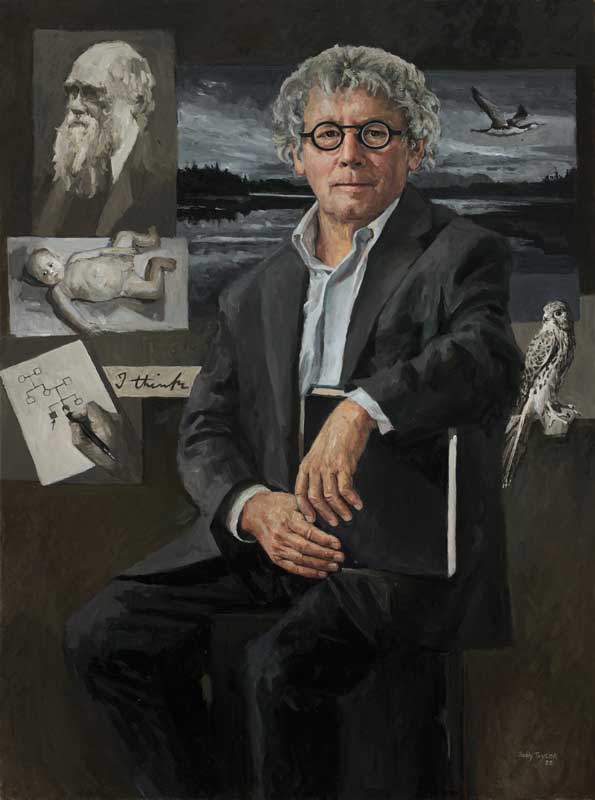

When I made an early December visit to Judy Taylor’s studio in Seal Cove on Mount Desert Island, the painter’s easel was occupied by a draft rendering of a portrait of Dr. Mark Anderson, former director of the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. The three-quarter standing figure had begun to emerge from the canvas, his features sketched in. Taylor planned to add elements related to his life and cardiology practice in the background.

Anderson is the third commissioned portrait Taylor has painted for Johns Hopkins. When completed, the painting will join a collection that features work by such eminent artists as John Singer Sargent, Cecilia Beaux, William Merritt Chase, and Jamie Wyeth. Taylor will attend the unveiling in June.

Judy Taylor’s portrait of David Lee Vallee, director of the Institute of Genetic Medicine at Johns Hopkins, is one of three she has painted for the prestigious school of medicine. David Lee Valle, oil on canvas, 2022, 39½ by 29½ in. David Lee Valle: Collection John Hopkins Medical Institutions

Judy Taylor’s portrait of David Lee Vallee, director of the Institute of Genetic Medicine at Johns Hopkins, is one of three she has painted for the prestigious school of medicine. David Lee Valle, oil on canvas, 2022, 39½ by 29½ in. David Lee Valle: Collection John Hopkins Medical Institutions

Over the years Taylor has painted numerous portraits for public and private collections. She also donates her portrait painting skills to good causes, including a series of live demonstrations to benefit the Southwest Harbor Library (her most recent subject was island gardener Eleanor Park).

“I’ve been drawn to the study of the figure and portrait in the narrative since I painted my grandfather on his farm in Nebraska when I was 12,” Taylor said. She considers it “essential training” to be able to understand the anatomy, form, and structure in order to paint life-like figures.

Taylor celebrates determination—and a Maine soft drink—in this jazzy painting. Moxie, oil on cradled panel, 2020, 24 x 12 in. Private collection. Photograph by James Imbrogno

Taylor celebrates determination—and a Maine soft drink—in this jazzy painting. Moxie, oil on cradled panel, 2020, 24 x 12 in. Private collection. Photograph by James Imbrogno

For a portrait titled Moxie, Taylor worked from a favorite model, Beth Woolfolk, who is solar coordinator for A Climate to Thrive on Mount Desert Island. “Not only does Beth take a pose,” the painter related, “she infuses a pose.” Taylor depicted her lying upside-down with her legs crossed where the X appears in the word Moxie. The piece is an homage to vintage advertising—and to a legendary Maine beverage—but it also reflects the figure’s bold spirit.

In Summer’s Return Taylor posed two red-headed nieces on the western side of Mount Desert Island before a distant prospect of Frenchboro. In this and other paintings of figures in the landscape, she seeks to prompt a narrative while emulating some of her favorite Ashcan School painters like George Bellows and Robert Henri. Among her best-known paintings in this category is Trail Workers, a tribute to Acadia’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which hangs in the Gates Center at College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor.

Taylor also paints pure landscape, her views marked by spirited brushwork and an eye for the season. In Maine she has painted nearby Bass Harbor and islands in the region, including the Cranberries and Swan’s. She also has taken a turn at Mount Katahdin, Portland, Harpswell, and Cape Elizabeth. And then there are the trips beyond the border: New York City, Austin, Florence, Rome, Venice, and London, as well as landscapes in the Pyrenees, the Loire Valley, Tuscany, Sicily, and Puglia. Wherever she paints, Taylor captures the lay of the land, sea, and shore.

Taylor stands before her community mural on Water Street in Ellsworth, before the Wabanaki symbols were added. Photo Kate Pickup McMullin

Taylor stands before her community mural on Water Street in Ellsworth, before the Wabanaki symbols were added. Photo Kate Pickup McMullin

As a muralist, Taylor gained a good deal of visibility, some of it unwanted, when then-Maine-Governor Paul LePage removed her history of Maine labor mural in 2011 after hearing from one person that it wasn’t sufficiently pro-business. What started as an ugly incidence of censorship ended on a positive note when the 11-panel, 36-foot-long piece was transferred in 2013 to the atrium of the Maine State Museum where thousands of visitors have since viewed it. When the museum reopens after renovations, a touch screen will allow a “deep dive” into the mural, with more than 160 related objects, photographs, and documents, plus interviews with the artist about its creation.

This past October Taylor completed another mural, an homage to the city of Ellsworth that graces the side of the Coastal Interiors building on Water Street. Seeking to come up with a design that “delivered the message of moving into the future with respect and regard for the past,” Taylor combined lively figures with various historical “reveals.” Colorful individuals of all ages (and a couple of creatures) dance, fly, run, and otherwise cavort in and among grayscale images from the shire town’s history. “It’s a great challenge to match an aesthetic to the content and one I relish,” she said.

Taylor reached out to First Nations poet, artist, storyteller, and activist Mihku Paul regarding her intention to include Indigenous tribes in one of the historical vignettes. The two agreed that it would be meaningful to have a tribal member involved in the actual physical painting. Paul subsequently came to Ellsworth and painted Wabanaki symbols above and below the tribal reveal. The Penobscot double curve design is specific to tribes in the region and is, according to Paul, “the oldest known decorative motif in our culture.”

Working with Heart of Ellsworth and a passel of committed volunteers, Taylor painted the mural over several weeks this past fall. “People on the ground, on the lifts, on ladders, organizers, getting along, supporting each other: it was truly a beautiful thing,” said the artist.

When she isn’t painting, Taylor teaches. She conducts intensive figurative and portrait workshops at and from (via Zoom) her studio and at Thomas Moser’s in Harpswell. She also leads landscape and figure painting sessions in Acadia National Park, Islesford, Austin, and the French Pyrenees.

For seven years running pre-pandemic Taylor took students to Italy to study in the museums and tour the Italian countryside. These expeditions featured culture, food, and history using local guides and “getting off the beaten track as much as possible.” She has also led trips to London and Paris where students spend every day sketching in the museums.

Taylor recalled how one of her groups was visiting the Louvre to see the Leonardo da Vinci show one week before the museum shut down due to Covid. “The last day, the Louvre opened up free for 24 hours, serving coffee and pastries to anyone who came in.”

Two red-headed nieces posed for Taylor’s evocation of the Maine coast. Summer’s Return, oil on linen, 2016, 30 x 40 in. Private collection

Two red-headed nieces posed for Taylor’s evocation of the Maine coast. Summer’s Return, oil on linen, 2016, 30 x 40 in. Private collection

Taylor started life in Nebraska but moved with her family several times in the early years as her father, who worked for Standard Oil, was transferred to Iowa, Kansas, and finally the northern suburbs of Chicago, where they settled. She earned a degree in advertising from the University of Illinois and subsequently took a job with an ad agency in the Windy City.

Taylor returned to “serious art study” at the American Academy of Art in Chicago before applying to the New York Academy’s pilot scholarship program in atelier study of the figure, a similar course of study to that taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. After two and a half years she moved to the National Academy of Art where she studied with figurative painters Ronald Sherr (1952-2022) and Harvey Dinnerstein (1928-2022). Study there was supplemented by drawing sessions at the Spring Street Studios where, Taylor recalled, “people came from all over to work in a dungeon with fabulous models.”

As an Acadia Artist in Residence in 1996, Taylor was introduced to, and fell in love with, Mount Desert Island. For a time, she divided her time between Maine and Texas, where she taught at the Austin Museum of Art, before becoming a full-time islander in 2002. Since then, she has embraced her adopted state with open arms and a loaded brush.

The pandemic prompted a pivot. While she couldn’t have models or teach in her studio, Taylor could provide online instruction. She started working with a group she knew in Austin every Saturday morning to paint portraits. Models sat live on Zoom. “People from all over hopped on for a three-hour portrait practice,” she reported.

This past January, Taylor led a group of artists from all across the country in the study of the George Bellows painting, Cleaning Fish, 1913, from the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. Live from her studio she broke down the composition of this iconic image of Monhegan fishermen, discussing composition and values, and urging her Zoom pupils to “start seeing graphically.”

Taylor has recently reopened her studio, by appointment only. She started traveling again last spring, returning to her beloved Italy. During the pandemic she has never stopped painting the Maine landscape, feeling blessed to have such a beautiful retreat in which to live and work. The benefits are bountiful.

✮

Carl and David Little’s fourth collaboration, The Art of Penobscot Bay, is due out in July from Islandport Press.

You can view more of Taylor’s artwork at www.judytaylorstudio.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.