Tradition Puts Maine Boatbuilders Ahead of the Curve

Maine Boatbuilders Ahead of the Curve

By Robert Stephens

Stephens, Waring, and White Yacht Design took inspiration

Stephens, Waring, and White Yacht Design took inspiration

from traditional Jonesport-style lobsterboat hulls when drawing Zogo. Photograph by Billy Black

A mere glance at the history of boatbuilding in Maine is enough to outline the grand tradition of marine construction in this water-girt region. From the spare and elegant canoes of birch and cedar crafted by the native populations to the first ocean-going vessel built by Europeans on this continent (the pinnace Virginia, launched in 1608 from the banks of the Kennebec River), through the grand downeasters of Searsport and the immense coasting schooners of Bath, Maine craftspeople have always maintained and furthered a tradition of careful, high-quality workmanship, a strong aesthetic sense, and above all excellent value. This tradition has endured into the twenty-first century, as Maine craftsmen have shifted their emphasis from commercial vessels to yachts and their tools from crooked knife, pencil, and plane to router, computer, and vacuum pump.

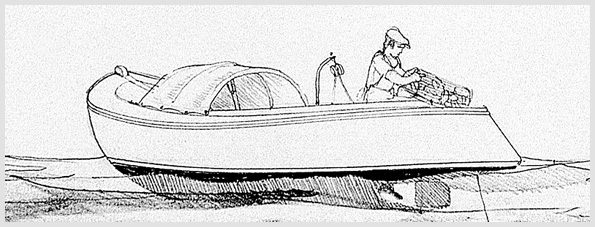

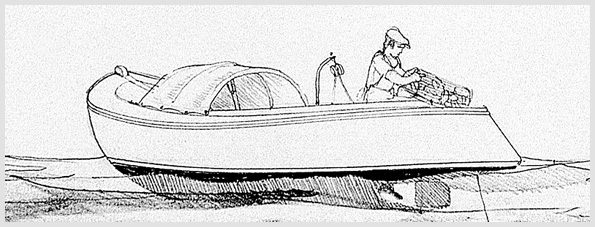

An early torpedo-sterned lobsterboat of the type fished out of Jonesport in the 1920s and 1930s,

An early torpedo-sterned lobsterboat of the type fished out of Jonesport in the 1920s and 1930s,

and an inspiration for Zogo.

What’s less obvious when one looks back over the history of boatbuilding in Maine is how this very tradition, along with the resourcefulness and ingenuity inherent to the Maine spirit, has provided Maine boatbuilders the tools to provide the world with a continuous stream of innovation in boat, ship, and yacht construction and design. A strong foundation of tradition has afforded us a sturdy jumping-off place from which to create new watercraft that are well-suited to an evolving world market, and new ways to combine old and new materials to make better, stronger, more seaworthy craft that continue to uphold our tradition of high value.

Just take a look at two examples mentioned above: the downeasters and the coasting schooners. As Maine shipbuilders emerged from the boom years of the clipper ships in the late 1850s, a new economic climate required a different solution from the fast, low-capacity, manpower-intensive clippers. The continued development of global trade meant that while speed of delivery was still important, carrying capacity and low operating costs became greater factors. Maine shipbuilders, uniquely positioned to take advantage of their knowledge of the tradition of clipper building, “detuned” the clipper design, and gave it greater cargo capacity, more stability, and a more manageable sail plan. The resulting downeasters, sailed by Maine captains and crews, were known the world over for their seaworthiness, speed, and beauty, and especially for the fortunes they made for their owners and captains. They served as the model for safe, efficient, and profitable vessels for the rest of the world even as the age of sail faded and sailing ships were pushed to the margins of world trade.

Then, as the downeasters became unprofitable, driven out of business by the high cost of maintaining a large sail-handling crew, Maine shipbuilders saw another niche to exploit. Drawing on hundreds of years of experience in the coastal trade with the Caribbean in highly efficient two-masted gaff schooners, Maine sailors and builders figured that if a little was good, more would be better. In the last years of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth, Maine shipyards built larger and larger schooners, culminating with the monstrous six-masted Wyoming, the longest wooden vessel ever built, launched in 1909 in Bath. These schooners, with their easily-handled rigs and steam-powered “donkey engines” to assist with hoisting sail, could be managed by very small crews—the standard rule of thumb was “a captain, a cook, and a man for each mast.” They remained profitable well into the 1900s, carrying coal and other bulk cargo along the Eastern Seaboard.

This understanding of tradition coupled with resourcefulness and ingenuity has continued to allow Maine builders and designers to respond nimbly to changes in the marketplace and in technology. As wooden shipbuilding faded in Bath, shipbuilders saw an opportunity to use their skilled crews and excellent waterfront facilities by shifting to first iron and then steel construction. This tremendous upheaval in shipbuilding technology was taken in stride by the company that became Bath Iron Works. As merchant ships became less profitable, Bath shipbuilders shifted their emphasis to naval vessels. When defense contracts temporarily dried up, they turned to yachts, building vessels as diverse as J. P. Morgan’s huge steam yacht Corsair IV and the legendary J-Class sailing yacht Ranger.

Bequia, designed by Stephens, Waring and White. A thoroughly modern yacht

Bequia, designed by Stephens, Waring and White. A thoroughly modern yacht

with traditional bones. Photograph by Alison Langley

In the twentieth century, Maine yards became the favorites of many East Coast yacht designers, who recommended Maine to their clients for high quality, strong work ethic, and great value for the dollar. Sailing yachts by the hundred were launched from the yards of Bath, Boothbay, Camden, and other smaller seaports, drawn by the likes of John Alden, Aage Nielsen, and William Hand. Then, after World War II, more change arrived. A changing economy meant a new market in moderately priced yachts for the newly affluent middle class. In response, advances in chemistry brought new, highly-touted composite construction processes to the market.

A few Maine companies, like Henry R. Hinckley of Southwest Harbor, played on their wartime mass-production experience to compete with production builders in other states and countries. Sticking with well-proven yachts of high pedigree, Hinckley was able to build an enviable reputation for a finely built yacht at a fair price. The Hinckley Pilot, series-built first in wood and then in the then cutting-edge material of molded fiberglass, cemented the firm’s niche as a first-class builder of solid, traditional yachts with a modern approach to construction. Over the next 50 years, Hinckley further consolidated its position with a series of cruiser-racer sailboats. Then in the early 1990s, Hinckley took the powerboat world by storm with its iconic Picnic Boat, a completely fresh look at the design parameters of the traditional Maine lobsterboat. Drawn by Maine designer Bruce King, the Picnic Boat, with its innovative jet drive, high-tech composite construction, and sweeping, graceful lines, gave the traditional lobsteryacht a modern aesthetic and usability.

By and large, though, Maine boatyards, accustomed to building high-quality custom yachts one at a time, were left behind by the changing markets of the 1960s and 1970s. Low-cost production yachts ruled the marketplace, and the Maine tradition of plank-on-frame wooden boatbuilding nearly died out. A few die-hards, among them Joel White of Brooklin Boat Yard, Luke Allen of Rockport Marine, and George “Sonny” Hodgdon of Hodgdon Yachts, banked the embers and kept the coals aglow. As the 1970s came to an end, they were able, with the help of a new generation, to breathe new life into an old trade. Their sons—Steve White, Taylor Allen, and Tim Hodgdon—following an ancient tradition of taking over the family business, worked with their fathers and a new crop of enthusiastic artisans to rebuild Maine’s custom yacht industry.

Key to this effort were two developments: first, epoxy glue led to the success of cold-molded wooden yachts, and second, boatbuilder and visionary Jon Wilson created a magazine and with it a market.

WoodenBoat magazine debuted in 1974. It preached the virtues of hand-crafted objects, specifically boats, and gave the remaining stalwarts simultaneously a way to communicate with each other and an avenue to reach potential clients.

Armed with new materials and a new champion, Maine boatbuilders set about to reinvent the custom yacht. Aware that clients had been attracted to Maine builders by their unique combination of traditional craftsmanship, high value, and the classic beauty of the yachts they had built, they have continued to offer the same recipe, enhanced with a modern perspective of design and performance today.

New ways of using that most traditional material, wood, have freed us to offer lighter, stronger, faster boats that require less maintenance and deliver greater satisfaction. Maine designers have kept abreast of developments in naval architecture, and have cherry-picked the most effective advances to enhance our boats. We now use cutting-edge design in the shapes of our keels and rudders (with always the practical eye to keeping boats slippery enough to make it through a maze of lobster buoys). Our towering rigs are now carbon fiber and our sails show the warm gold glow of Kevlar. The lines of our yachts more often than not feature the long, graceful overhangs of yesteryear, but our deck hardware includes the newest, lightest, lowest-friction equipment. Our clients enjoy the thrill of driving their gleaming, hand-built objets d’art through squalls and across finish lines without fear of damaging an antique museum piece, but still basking in the admiring gaze of dock-walkers at the end of the day. Our yachts are known world-wide for their traditional beauty, state-of-the–art performance, and reasonable cost.

As new challenges face Maine’s boatbuilding industry today, we find ourselves responding in spirit much as our forebears did. Looking to past experience for inspiration, we lean on our knowledge to lever ourselves into an exciting and rewarding future. And there’s never been a more exciting time to be a Maine boatbuilder. For the last decade, we have been experiencing sweeping changes in materials technology that allow us to make better, stronger, faster boats of higher safety, greater efficiency and beauty, and more value than ever before. And unlike builders elsewhere in the country, who move grudgingly to new technology to comply with government regulations, we eagerly embrace these technologies because our tradition of successful response to change and opportunity has shown us that change is good. If we can build a better boat for our customer, we stand a better chance of keeping that customer. We’ve been seeking market niches and developing products to exploit those niches for centuries—it’s in our DNA.

More changes are on the way, and Maine is perfectly positioned to ride the wave. Propulsion technology is about to see a big shift, as fossil fuels become more dear, greenhouse gas emissions take the moral and regulatory forefront, and leaps in battery technology allow more energy to be stored in a smaller, lighter package.

Right now, a small yacht that was designed by a Maine design firm and built at a Maine boat shop, and that uses the first diesel-electric hybrid drive imported for sale into the U.S., is enjoying its premier season on Maine waters. This little launch will give its owners the great pleasure of cruising silently among the islands of Merchants Row, while solar panels on the canopy pour renewable energy into the battery banks, and a reliable, clean-burning diesel lies at the ready for peace of mind, high-speed weather evasion, and battery charging as necessary.

The hull shape harks back to the slippery lobsterboats of 1930s Jonesport, when small automotive gasoline engines provided limited power and high-efficiency hulls were of prime importance. This launch will be only the first of a new style of Maine powerboat. Our tradition of delight in the pristine beauty of our water and air will encourage Maine builders to embrace the changes that will bring boatbuilding to a more ecologically conscious mind-set—and we will once again be ready to fill a niche in the world market. Our traditions will put us ahead of the curve.

What is it that frees Maine boatbuilders and designers to apply such innovative thinking without losing the thread of what makes a boat a Maine boat? It’s the solid footing of our hundreds of years of tradition and collective experience. As a designer, I find myself asking “Why can’t we do it like THIS,” and the answer is informed by our collective history. Boat design has always been an evolutionary process—each small new development is based on the bloodline of similar previous craft. Revolutionary jumps in design and technology are not to be trusted, not with your life in rough weather. Our solid understanding of the tradition of boat design and construction gives us the solid basis to freely make incremental improvements in shape, structure, and materials technology without losing sight of what makes a good Maine boat--careful, high-quality workmanship, strong aesthetic sense, and above all excellent value.

Bob StephensBob Stephens is a yacht designer at the firm of Stephens, Waring, and White in Brooklin, Maine. He has been involved in the design and construction of “Spirit of Tradition” yachts on the Maine coast since the early 1980s.

Bob StephensBob Stephens is a yacht designer at the firm of Stephens, Waring, and White in Brooklin, Maine. He has been involved in the design and construction of “Spirit of Tradition” yachts on the Maine coast since the early 1980s.

Stephens, Waring, and White Yacht Design took inspiration

Stephens, Waring, and White Yacht Design took inspiration from traditional Jonesport-style lobsterboat hulls when drawing Zogo. Photograph by Billy Black

An early torpedo-sterned lobsterboat of the type fished out of Jonesport in the 1920s and 1930s,

An early torpedo-sterned lobsterboat of the type fished out of Jonesport in the 1920s and 1930s, and an inspiration for Zogo.

Bequia, designed by Stephens, Waring and White. A thoroughly modern yacht

Bequia, designed by Stephens, Waring and White. A thoroughly modern yacht with traditional bones. Photograph by Alison Langley

Bob Stephens

Bob Stephens

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.

Zogo is powered by a solar-assisted diesel-electric drive. Photograph by Billy Black.

Zogo is powered by a solar-assisted diesel-electric drive. Photograph by Billy Black.