Modern Pictures at an Exhibition

Masterpieces from the Paley Collection, on view at the Portland Museum of Art, spur remembrances of epiphanies past

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) Odalisque with a Tambourine. Nice, Place Charles-Félix, winter 1925-26. Oil on canvas, 291⁄4 x 217⁄8. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, William S. Paley Collection (2)

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) Odalisque with a Tambourine. Nice, Place Charles-Félix, winter 1925-26. Oil on canvas, 291⁄4 x 217⁄8. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, William S. Paley Collection (2)

The memories begin with Cézanne. While studying the three oils and two drawings by the French master in the exhibition “The William S. Paley Collection: A Taste for Modernism” at the Portland Museum of Art, I am carried back to the fall of 1977.

I am living in my home city of New York, having graduated from Dartmouth the year before. My mother suggests I pay a call on her brother, my Uncle Bill, the painter William Kienbusch. Soon, I am a regular visitor at his apartment on East 80th Street, stopping by in the evening to talk art and poetry.

The memories continue. The Museum of Modern Art has opened “Cézanne: The Late Work.” My uncle’s health is declining—he has a difficult time getting around—but he must see this show. We take a cab to MoMA on a weekday morning and are the first in line. As planned, once inside we walk to the end of the exhibition and then retrace our steps, resting every few minutes. This way, there is no crowd and we can be leisurely in our looking.

Cézanne is god. My uncle doesn’t say this, but time and again he points to the painter’s work as the talisman, the touchstone, of so many artists that came after him, including a favorite of his from Maine, Marsden Hartley. Uncle Bill can trace his own aesthetic on the museum’s walls: his early work displayed a cubist idiom that grew out of Cézanne. And surely his obsession with the abandoned granite quarries on Hurricane Island owed something to the Frenchman’s paintings of the chiseled sandstone pits at Bibémus in Aix.

Today, as I walk through the Paley collection, memories of such art encounters arise time and again. Here are the painters I grew up with, who shaped my perceptions of art but also of the world around me. I greet them like old friends.

Ah, Odilon Redon, mon ami! Redon’s Vase of Flowers, circa 1912-1914, sweeps me back to my mother’s studio on Long Island, New York, where she painted her arrangements of daisies and daffodils, butterfly weed and lilac. She loved Redon, master of the floral still life, more than Redon, master of the macabre. A framed print of one of his flower pieces hung on her wall for years.

My mother also loved Henri Matisse, he of the daring Fauvist hues and decorative interiors inhabited by women dressed in wild outfits or in various stages of undress. The Paley collection features outstanding examples of these figure pieces: an odalisque with tambourine; a veiled woman wearing what appears to be a patterned tablecloth; a brunette accompanied by a vase of narcissuses, and another with anemones. The freedom of Matisse’s colors and compositions offered my mother license to paint outside the box, to let her flag fly free.

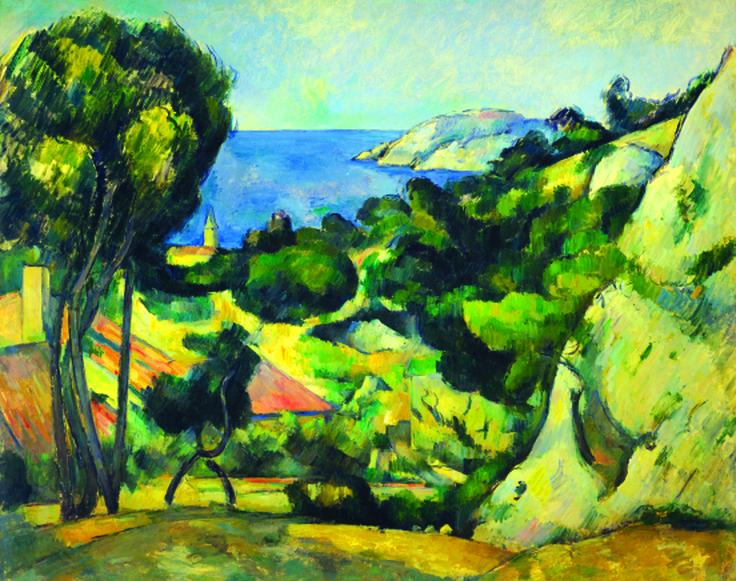

Hints of the Maine coast: Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). L’Estaque, 1879-83. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2" x 39"

Hints of the Maine coast: Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). L’Estaque, 1879-83. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2" x 39"

Another memory is revived when I see these paintings. In the early 1980s, while working for Lucien Goldschmidt, a prints and drawings dealer in New York City, I met Matisse’s grandson, Claude Duthuit. Monsieur Duthuit had arranged to have Mr. Goldschmidt be the American distributor for a portfolio, Pasiphaé—Chant de Minos, which featured 90 never-before-seen linoleum cuts composed by Matisse.

When my wife, Peggy, and I, and our infant daughter, Emily, lived in Paris in 1985, I looked up Monsieur Duthuit. He invited us to dinner at his house. He and his wife, Barbara Dauphin-Duthuit, provided a delicious dinner that concluded with several glasses of pêcher mignon, a delicious peach liqueur. Madame Dauphin-Duthuit sent us home with a stuffed white cat for Emily—her companion for the rest of our stay in the City of Lights.

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). The Seed of Areoi, 1892. Oil on burlap, 361⁄4" x 283⁄8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, William S. Paley Collection.

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). The Seed of Areoi, 1892. Oil on burlap, 361⁄4" x 283⁄8". The Museum of Modern Art, New York, William S. Paley Collection.

The Paley collection includes a few, shall we say, curveballs. For example, in the midst of what is for the most part a French-art love fest, from Bonnard to Vuillard, one encounters a lone watercolor by Edward Hopper.

“Modern” is not the first adjective that comes to mind when one thinks of Hopper. Indeed, he was about as conservative in his tastes as any painter ever was. According to his biographer, Gail Levin, in the spring of 1960 he met with a group of artists to protest the “gobbledygook influences” of abstract art at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art.

Kienbusch passed on his artistic fascinations to the author, his nephew, who then built a career around art. William Kienbusch. Quarry Hill, Hurricane Island, 1955 Casein on paper, 21 1/2" x 27 3/8". Farnsworth Art Museum Collection, bequest of Mrs. Elizabeth B. Noyce, 1997.3.26

Kienbusch passed on his artistic fascinations to the author, his nephew, who then built a career around art. William Kienbusch. Quarry Hill, Hurricane Island, 1955 Casein on paper, 21 1/2" x 27 3/8". Farnsworth Art Museum Collection, bequest of Mrs. Elizabeth B. Noyce, 1997.3.26

Yet the watercolor on display, Ashe’s House, Charleston, South Carolina, 1929, is not without its modernist touches. The arrangement of clapboards, shutters, and shadows on the flat-roofed residence echoes the geometric abstractions of some of the painter’s contemporaries. As much as Hopper disliked having his paintings aligned with contemporary work—he is said to have remarked “You kill me” when the critic Lloyd Goodrich compared one of his paintings to an abstraction by Piet Mondrian—the connection is there.

For me, the Hopper painting speaks of a sense of place—and calls to mind my first encounter with the artist, which came while I was growing up in New York. One year, the cover of the Manhattan telephone directory featured Early Sunday Morning, 1930, one of the most famous of his city paintings. I sent in a coupon and received a poster of the painting, which hung in my bedroom for many years. To this day, this image of a row of shops in bright sunlight brings back memories of lingering in front of the stamp store on my way to Sunday school.

The three Gauguin paintings in the collection inspire a more recent remembrance of things past. In 1999, while directing the Ethel H. Blum Gallery at College of the Atlantic, I was offered a most appealing assignment: fly to Chicago to select 25 or so Gauguin watercolors, drawings, and prints from the collection of COA trustee Edward Blair and his wife, Elizabeth, for a show at the college.

After arriving at O’Hare airport, I found my way to the Blairs’ home in Lake Bluff on the outskirts of the city. There, on the walls of their modern house, hung the Gauguins, all of them related to the painter’s sojourns in the South Pacific in the late 1800s. Needless to say, I relished the task of making the selection.

Ed Blair’s two great passions in art, Gauguin and John Marin, were tied to his favorite places in the world, the South Pacific and Maine. He made regular trips to Tahiti to reconnect with that paradisiacal world. In a similar manner, he would explore the archipelago of downeast Maine, drawn by the light but also by a passion for whales: College of the Atlantic’s Edward McCormick Blair Research Center on Mount Desert Rock is named for him.

Every major collector of the modern must own a Picasso, and William Paley was no exception. The group he gave to the Museum of Modern Art offers choice examples: Boy Leading a Horse, 1905-1906, from Picasso’s “Blue Period”; Nude with Joined Hands, 1906, inspired by Fernande Olivier, one of the painter’s mistresses; and two still lifes, including The Guitar, 1919, in which the musical instrument, in the words of art historian Matthew Armstrong writing in the catalogue for the show, is treated “in a variation of the penetrating, dismembering language of Cubism.”

Here the paintings return me once again to Paris, and the first visit my wife and baby daughter made to the Musée Picasso. The then-new museum, housed in a renovated seventeenth-century townhouse (hôtel particulier), presented a stunning cross-section of the Spaniard’s artwork, from early realism, through Cubism and collage, to the final expressive work of his last years.

How could a single artist have been responsible for this diverse work? Around each corner, in each room, a surprise awaited us. The playfulness of much of the work cast its spell. We have a photo of Emily on all fours headed for one of Pablo’s remarkable sculptures.

You might say the closest thing to Maine in the Paley collection show is Cézanne’s L’Estaque, 1879-1883, a view of a coastal village near Marseille. (The painting once belonged to the Impressionist painter Claude Monet and hung in his home in Giverny.) The steeple in the distance might be the Somesville Union Meeting House; the headlands that nudge the horizon at upper right recall Gull Rock and other promontories on Monhegan; and the pine trees and outcroppings bring to mind any number of seacoast locales.

In making this connection, I realize my world-view has shifted since moving from New York City to Mount Desert Island in 1989. I am now a Mainer. I filter art and just about everything else through the prism of my immediate surroundings. Yet that passion for the modern has never left: a pastel of the Islesford Dock by painter Dan Fernald that hangs in our dining room has a distinctly Fauvist feel, while a study of iceboats on Damariscotta Lake by Richard Saltonstall has the dynamic energy of Kandinsky.

As I watch my son James stand in front of a painting of bayberry and ocean by my Uncle Bill, smiling as he drinks in its tangles of expressionist brushstrokes, I feel as if I’ve come full circle—from a Cézanne exhibition I saw so many years ago to a life built around art. I am grateful to the Portland Museum and the late Mr. Paley for helping me make this journey through time.

Carl Little’s latest book is Nature & Culture: The Art of Joel Babb (University Press of New England). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

“The William S. Paley Collection: A Taste for Modernism” is at the Portland Museum of Art through September 8, 2013. The PMA is the only New England venue for this exhibition, which travels next to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in Quebec City (October 10, 2013-January 5, 2014) and ends at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas (February-April 2014).

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.