Searching for a Safe Harbor

Maine Native Artist Earl Cunningham

Photographs courtesy of The Mennello Museum of American Art, owned and operated by the City of Orlando

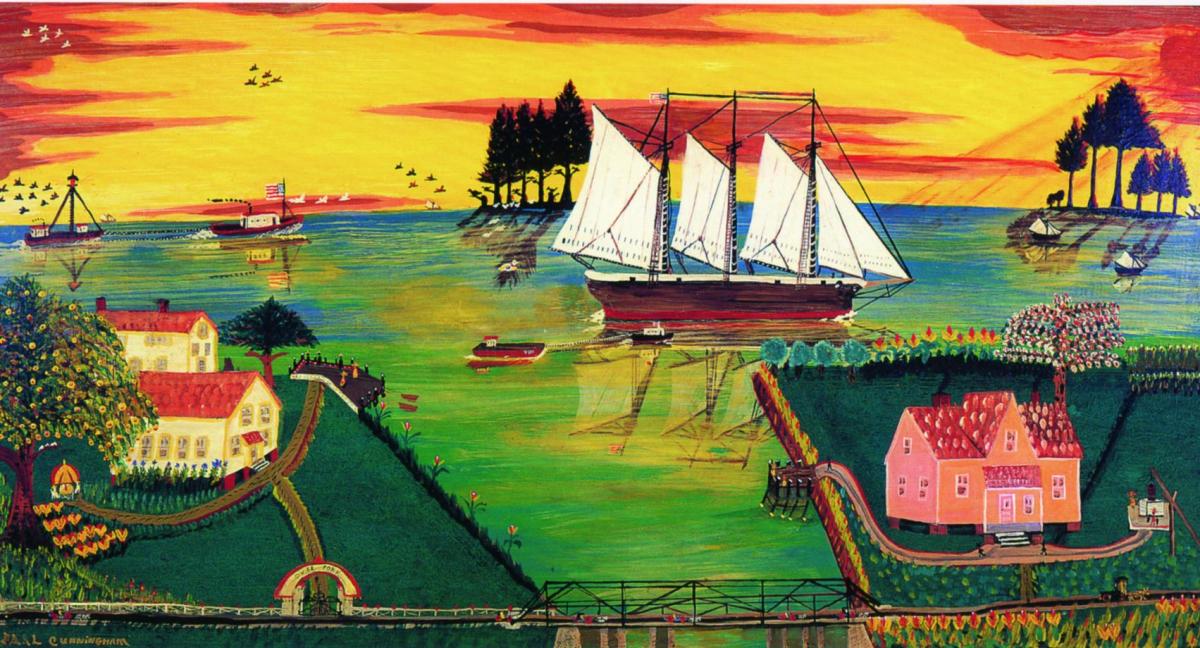

When you look at one of the late Earl Cunningham’s paintings, the first thing you notice is the color, vibrant, “fabulously technicolored” as critic Roberta Smith wrote in the New York Times. Then you notice the disproportionate sizes and impossible pairings: a bird the size of a canoe, or snow-topped palm trees, always adjacent to one body of water or another and always within reach of a harbor. You would not be wrong if you decided that these images, combining past, present, and distant geographies, are the personal visions of an eccentric, highly original artist.

Summer Day at Over-Fork perfectly illustrates Cunningham’s style, which included a technicolor palette, disproportionate sizes, and unlikely pairings of objects and places.

Summer Day at Over-Fork perfectly illustrates Cunningham’s style, which included a technicolor palette, disproportionate sizes, and unlikely pairings of objects and places.

Although most people associate Cunningham with Florida where he spent much of his life and where he died in 1977, this acclaimed folk artist was a Mainer.

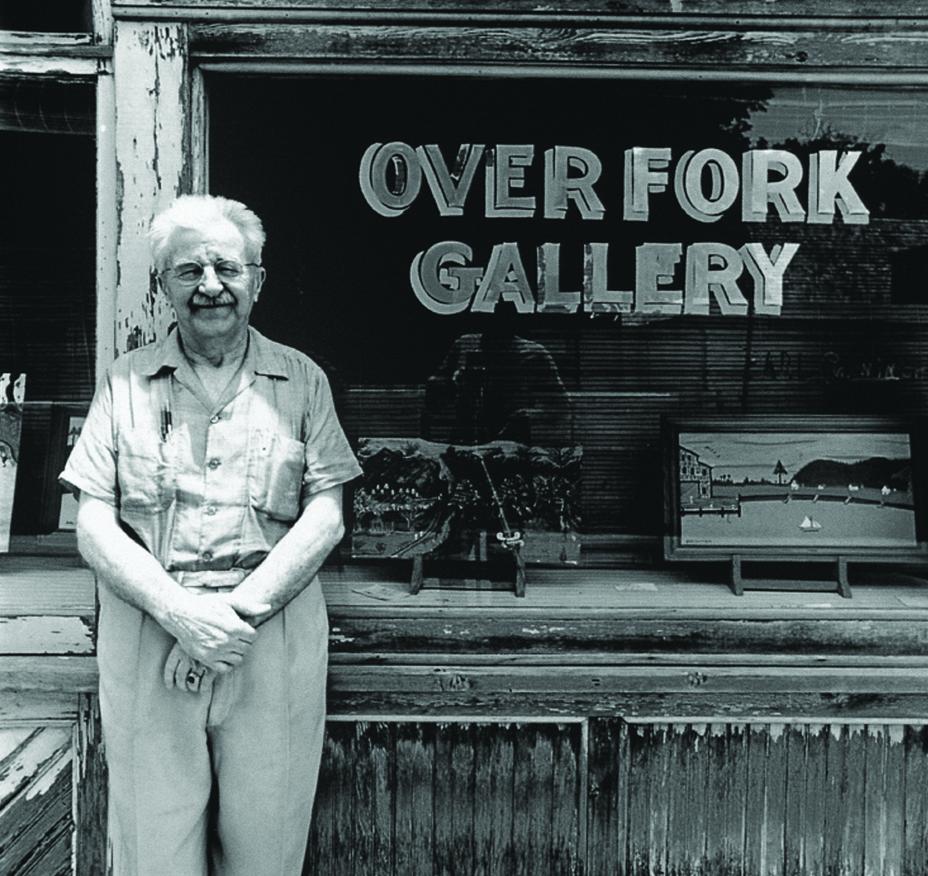

Cunningham poses in front of his shop and gallery on St. George Street in St. Augustine, Florida. He modified the Cunningham clan motto, “Over Fork Over” when he named it.

Born in 1893, Earlond Rondol (his real name, according to his grand-nephew Chuck Cunningham) grew up on the family farm in Boothbay in a house once owned by a sea captain. He worked on the farm with his brothers and sisters and played the guitar at family gatherings. He was kind to his young niece Bernice and collected lily pads for her to sell from her road-side stand. He dutifully followed his mother’s wishes not to leave home before eighth grade.

Cunningham poses in front of his shop and gallery on St. George Street in St. Augustine, Florida. He modified the Cunningham clan motto, “Over Fork Over” when he named it.

Born in 1893, Earlond Rondol (his real name, according to his grand-nephew Chuck Cunningham) grew up on the family farm in Boothbay in a house once owned by a sea captain. He worked on the farm with his brothers and sisters and played the guitar at family gatherings. He was kind to his young niece Bernice and collected lily pads for her to sell from her road-side stand. He dutifully followed his mother’s wishes not to leave home before eighth grade.

Then at age 13 or so, he set off to begin a hardscrabble life. He lived in a shack on Stratton Island near Old Orchard Beach (remnants still exist), then sailed along the East Coast in a 22-foot schooner, took a course in automobile engineering in Portland, and became a licensed harbor and river pilot. It was at this time he first started painting, using whatever materials he could scavenge, often house paint and discarded wood, and he sold his work for as little as 50 cents.

Even decades after Cunningham moved away, Maine’s landscape and seasons played a predominant role in his paintings, as in New England Autumn with its warm orange and yellow hues.

Even decades after Cunningham moved away, Maine’s landscape and seasons played a predominant role in his paintings, as in New England Autumn with its warm orange and yellow hues.

He married Westbrook-born Iva “Maggie” Moses in 1915 when she was 29 and he was 22, and settled in Freeport as a “junk dealer,” according to local census records. At first the couple lived on a cabin cruiser named Hokona (possibly on the Harrasseeket River since there’s a picture of him there in 1916) and then in town on School Street, which is probably now the parking lot for St. Jude’s Catholic Church. When that house burned, the couple outfitted a truck, named it Dirigo (after the Maine state motto) and began a peripatetic life, moving between Florida and Maine for about 15 years. They searched for items in Florida to bring back to sell in Maine, and took time off to do a bit of sightseeing, too: There’s a photo of Maggie at Niagara Falls in August 1921.

By 1930, Cunningham’s home base was a small farm in Boothbay, across the street from the family’s much larger farm. The couple divorced in the mid-1930s (they had no children), and his father died in 1935. Possibly these factors led to Earl Cunningham’s decision to sell his farm and leave Maine. A parcel of newspaper clippings Cunningham sent home and a visit from his nephew and wife in Florida were his only contact with his family for the rest of his life.

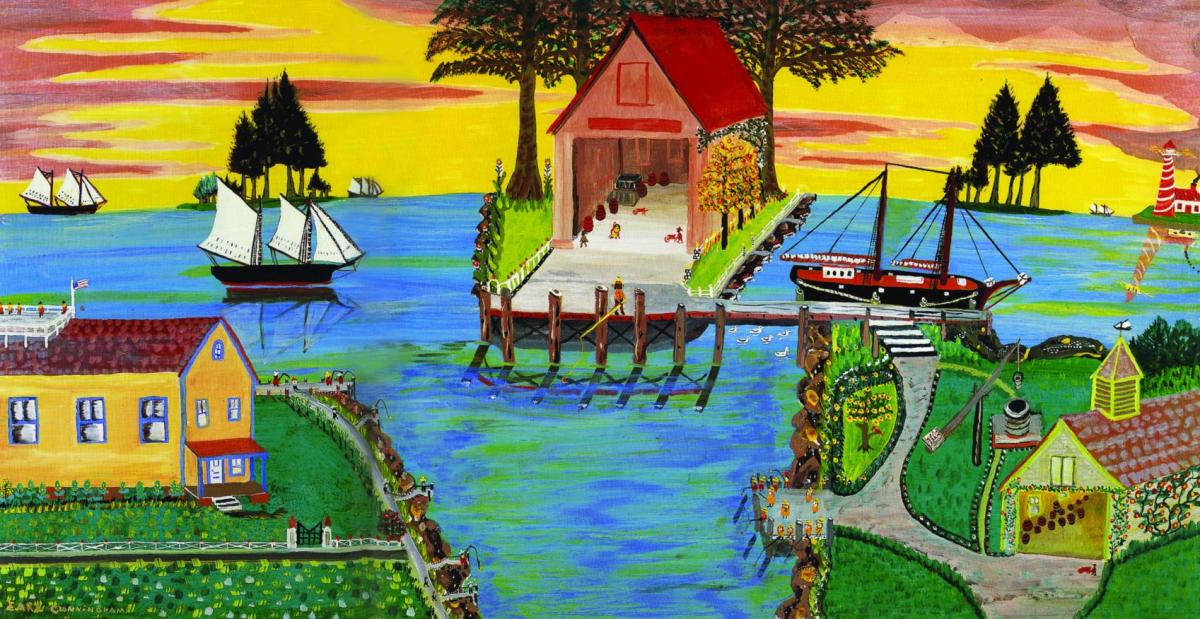

Pine trees, boathouses, and schooners are motifs that often appear in Cunningham’s vibrant paintings of an idealized Maine, such as this painting, Sunrise at Pine Point.

Pine trees, boathouses, and schooners are motifs that often appear in Cunningham’s vibrant paintings of an idealized Maine, such as this painting, Sunrise at Pine Point.

Cunningham moved first to a 50-acre farm in South Carolina where, during World War II, he raised chickens for the Army. After the war, in his fifties now, he settled in St. Augustine, Florida, and opened Over Fork Gallery, a “curio shop.” (“Over Fork Over” is the Cunningham clan family motto, but he also joked that to call his shop “Fork Over” would have been too obvious.) There, glass cases contained bottles, figurines, lamps, china plates, and oddities of all sizes, and hundreds of his colorful, eccentric paintings hung floor to ceiling. Cunningham wore a beret and an artist’s smock to look the part. While he had a sense of humor, he took his work seriously, using professional paints and artist supplies. His goal, he wrote, was to paint 600 paintings in order to have a museum.

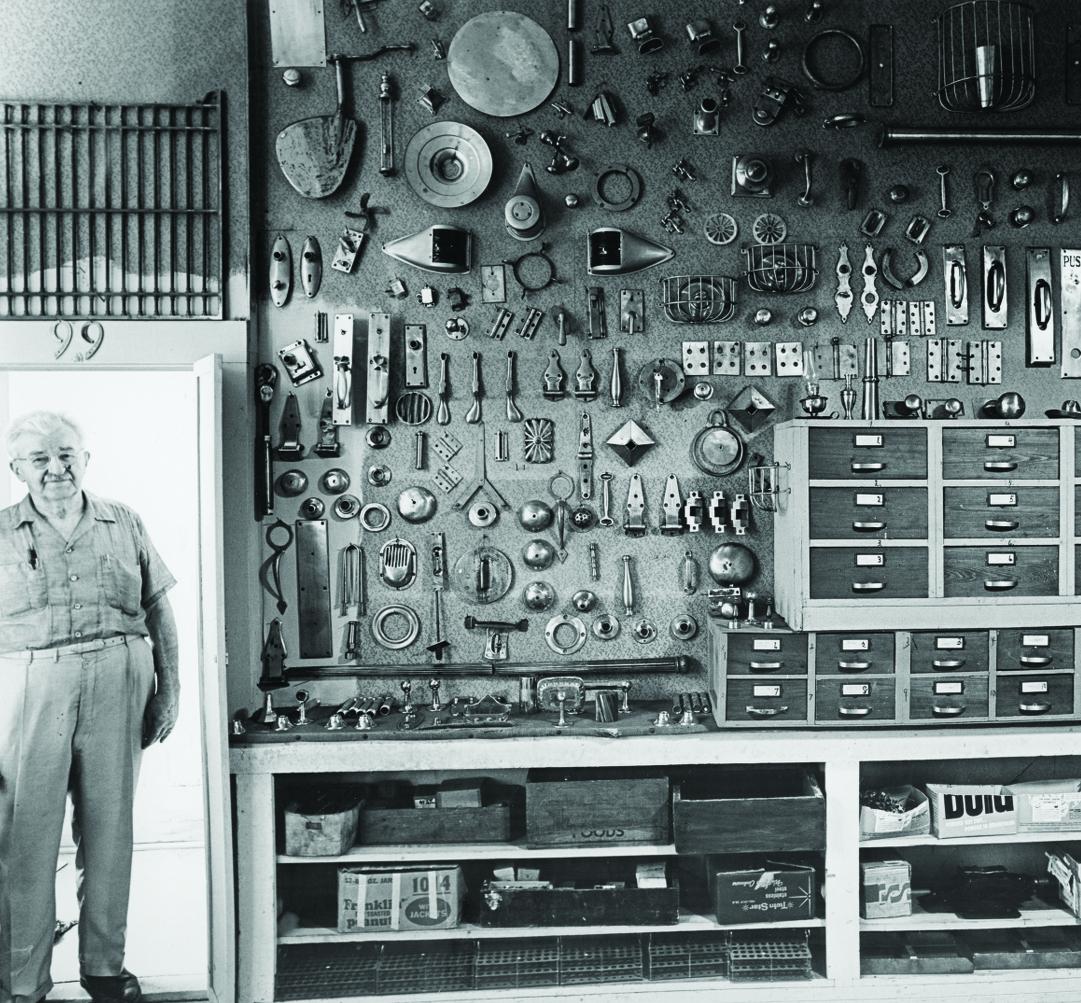

The interior of Cunningham’s shop was filled floor to ceiling. He was sometimes known as the “Dragon of St. George Street” because of his curmudgeonly behavior.

As he grew older, though, Cunningham became increasingly eccentric. He began to obsess about thieves. He worried that his store, located in a historic district, was going to be burned by the local preservation society to make room for a parking lot. He thought women pushed their shopping carts into him at the supermarket. Still, he continued to paint, even when he relocated the shop to another location in the city. By the end of his life, he had created close to 450 paintings.

The interior of Cunningham’s shop was filled floor to ceiling. He was sometimes known as the “Dragon of St. George Street” because of his curmudgeonly behavior.

As he grew older, though, Cunningham became increasingly eccentric. He began to obsess about thieves. He worried that his store, located in a historic district, was going to be burned by the local preservation society to make room for a parking lot. He thought women pushed their shopping carts into him at the supermarket. Still, he continued to paint, even when he relocated the shop to another location in the city. By the end of his life, he had created close to 450 paintings.

Most critics have labeled this self-taught artist’s work as “folk art” or “naïve.” Cunningham referred to himself as a “primitive artist” and even as “Grandpa Moses,” after Grandma Moses in the 1950s. Recently, Cunningham has been identified as an “American Fauve” (the catalogue title for a 2011-12 exhibition), since his paintings radiate with the brilliant colors of the French Fauvist movement. Some have labeled the work “fantasies,” but Frank Holt, former director of the Mennello Museum, which holds the largest collection of Cunningham’s art, disagrees. Cunningham was painting what he knew—boats, birds, harbors, Maine, and Florida—but with his own twist.

Some might also call his work “Outsider Art,” for Cunningham was both self-taught and outside the artistic establishment. His personality further alienated him, as he was often gruff and cantankerous.

He was also a crusty New Englander. No matter how far away he was geographically, Maine resonated in his imagination and in his paintings. Some paintings seem to depict Cunningham’s idealized notion of Maine, such as “Pine Point” (which refers not to the Scarborough beach but a cove on his family farm) and “Perkins Cove” in Ogunquit. Some works feature iconic Maine elements like lighthouses. Pine trees and boathouses appear repeatedly, and sailing vessels of all sizes and varieties

are ubiquitous, especially the large schooners that plied the Maine coast when Cunningham was a boy.

Critics have noted Cunningham’s tendency to juxtapose locations and time; a good example is “Nassau Sound.” The painting of a bay in northern Florida incongruously includes a pine forest and New England schooners. In “The Twenty-One” and “Ship Chandlery with Angel,” palm trees appear in typical New England waterfront scenes. Viking ships rest at anchor in “Perkins Cove.”

Added to this is his peculiar sense of scale. Although folk art often includes disproportion, Cunningham brings it to a whole new level: A railroad looks like a model train in one painting, and in another, houses resemble Monopoly pieces. People are as tiny as mice, while a bird the size of a one-story building sits atop a palm tree. This may be Cunningham’s way of commenting about the insignificance of man-made institutions, such as railroads and houses, compared with nature.

Indeed, the natural world for Cunningham is massive and powerful, whether mountains, volcanoes, or, especially, bodies of water. That’s the real key to this Mainer’s artistic world: as befits a man who grew up by the sea, his works always include water, and without fail, a boat—a Viking ship, a schooner, or an Indian birch bark canoe. Significantly, though, these boats are not at sea. There’s always a harbor or land nearby, always a “protective land barrier,” as Robert Hobbs, author of Earl Cunningham: Painting an American Eden, points out. Frank Holt agrees: This is a marine painter who paints ships within reach of a safe, comfortable harbor, not far from home—quite possibly a commentary on Cunningham’s own personal search for home.

Two women changed the course of Cunningham’s life. The first, Theresa “Tese” Paffe was Cunningham’s landlord in St. Augustine as well as his “lady friend.” She made it possible for him to close his door to the world (literally) and paint. They talked of marriage, but his arguments with a Catholic priest apparently put an end to that, and the pair eventually broke off their relationship. It was likely she who found him on December 29, 1977, after he shot and killed himself, an act that most have attributed either to that break-up, long-standing depression and paranoia, or illness—or a combination of all factors. It fell first to her and then to his nephew Robert Cunningham and niece Bernice Spinney—who drove down from Maine—to sort through his possessions and paintings.

The second woman, Marilyn Langsdon Mennello, brought him fame. A long-time fan of American folk art, she and a friend walked into the Over Fork Gallery in 1969 and fell in love with Cunningham’s colorful paintings displayed along with a prominent Not for Sale sign (now preserved at the Mennello Museum). He refused at first to sell her anything. In the end, though, she wore him down—and her advocacy of his art and their personal connection transformed his life.

Today, the family farmhouse in Boothbay remains much as it was when Cunningham was a child. Photo by Francis J. Waters

Marilyn and her husband, Michael Mennello, made it their mission to bring Cunningham’s art to the world. They bought what they could and she arranged two exhibitions, a one-man show in 1970 at a gallery that later became the Orlando Museum of Art and another at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Daytona Beach. In 1998 they founded the Mennello Museum of Folk Art in Orlando, now the Mennello Museum of American Art, the base of which is their collection of Cunningham’s work.

Today, the family farmhouse in Boothbay remains much as it was when Cunningham was a child. Photo by Francis J. Waters

Marilyn and her husband, Michael Mennello, made it their mission to bring Cunningham’s art to the world. They bought what they could and she arranged two exhibitions, a one-man show in 1970 at a gallery that later became the Orlando Museum of Art and another at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Daytona Beach. In 1998 they founded the Mennello Museum of Folk Art in Orlando, now the Mennello Museum of American Art, the base of which is their collection of Cunningham’s work.

Nearly 20 years later, the Smithsonian Institution launched a traveling exhibit that finally brought this Maine native national acclaim. Besides the exhibit catalogue, Earl Cunningham’s America, by Smithsonian curator Virginia Mecklenburg and others, articles appeared in major newspapers. The Kennedy Center has a painting that Cunningham himself donated to the White House (after Jackie Kennedy visited his gallery in St. Augustine). His paintings have been acquired by major museums in New York City, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and Boston, and in 2011-2012, his work was featured in galleries in Wyoming and California. The Winter Park (Florida) Public Library maintains his archives, and he was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame in 2003.

In Maine, the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland hung a show in 1996, but otherwise, this Maine native is largely unknown here. He’s not represented in the collections of the state’s major art museums and is rarely mentioned in books on Maine artists. In a state that has welcomed artists for centuries and where artist colonies have thrived, it’s time for Maine to claim this native.

Erika J. Waters, Ph.D. was an English professor at the University of the Virgin Islands and, more recently, an adjunct at the University of Southern Maine. She currently divides her time between Maine and Florida, where she sails with her husband, a former charter boat captain, and where she’s at work on Discovering Old Florida—which is how she “discovered” Earl Cunningham.

With thanks to Chuck Cunningham, Nancy Lowell Cunningham, and Bernice Spinney; Marnie Mitchell and Barbara Rumsey of the Boothbay Region Historical Society; Holly Hurd of the Freeport Historical Society; Bob Fusselman, and Paul T. Cunningham (no relation); Virginia Mecklenburg, Chief Curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; and Frank Holt, former director of the Mennello Museum of American Art. A special thank you to Lindy Shepard and the Mennello Museum for the images.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.