Something in the Water?

Harpswell as literary muse

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote parts of Uncle Tom’s Cabin while enjoying the view from Orrs Island, Harpswell, in the 1850s. A century later in the 1960s, novelist Elizabeth Strout found inspiration at the town’s Bailey Store.

In between, despite its small population—only 5,000 these days, counting summer residents—Harpswell has inspired fiction, poetry, drama, and even multiple North Pole memoirs. More than 15 writers are associated with Harpswell, including three Pulitzer Prize winners.

The town’s natural beauty and elevated, panoramic views no doubt contributed to this unique literary flowering. As early as the middle of the 19th century, hotels were built here, and soon, steamboats were bringing tourists for holidays. Bowdoin College, just a few miles down the road, also introduced students and their families to the area.

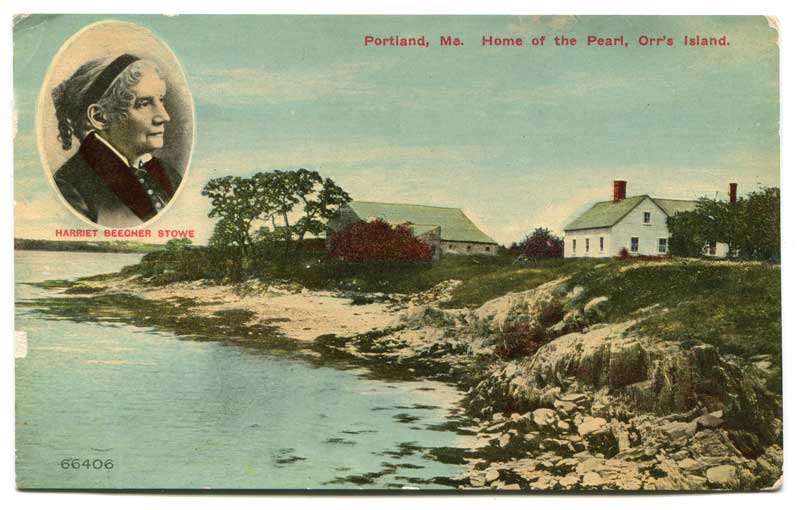

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s popularity after Uncle Tom’s Cabin ensured that tourists would purchase postcards of The Pearl of Orr’s Island. Courtesy the author

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s popularity after Uncle Tom’s Cabin ensured that tourists would purchase postcards of The Pearl of Orr’s Island. Courtesy the author

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896):

While her husband taught theology at Bowdoin, Harriet Beecher Stowe was hard at work on Uncle Tom’s Cabin. To relax, the family would rent a house on Orrs Island, near the steamboat landing. While sitting there, she conceived a story about the island, but she put it aside.

Then, after her son tragically drowned at Dartmouth College 10 years later, she found solace at Orrs Island and picked up the story again. It became The Pearl of Orr’s Island: A Story of the Coast of Maine, the story of a girl who was raised by a sea captain grandfather. The novel, which is considered a prime example of New England “local colorism,” has been praised for its authenticity, particularly its use of the Maine dialect.

Elijah Kellogg was such a beloved pastor that this Congregational Church was named for him. He was pastor there for nearly 50 years. Photo courtesy of Penobscot Maritime Museum

Elijah Kellogg (1813-1901):

Elijah Kellogg was such a beloved pastor that this Congregational Church was named for him. He was pastor there for nearly 50 years. Photo courtesy of Penobscot Maritime Museum

Elijah Kellogg (1813-1901):

It’s entirely likely that Stowe, as a theology professor’s wife, might have passed an evening in the company of Elijah Kellogg, a Bowdoin graduate and a much-loved Congregationalist minister in Harpswell. Kellogg was a hands-on pastor, never hesitating to help parishioners in need.

Despite his demanding career, he found time to write more than 30 adventure books for boys, the most famous being the Elm Island series, based on nearby Ragged Island. The first book, Lion Ben, begins with detailed descriptions of the island’s geography.

His biographer, Wilmot B. Mitchell, noted Kellogg’s realism: “His carpenters are not fishermen; his sailors are not landlubbers.” This was undoubtedly true because Kellogg knew Harpswell and its people so well. As a young boy, he would explore local islands in his sailboat. Later he used a 23' double-ender that was built at the Durgin boatyard on Birch Island to visit his parishioners; the skiff is now in the collection of Mystic Seaport.

His flock didn’t forget him when he was old and poor. They held donation parties and left food and clothing hidden around his house. But when someone gave him a winter coat, he gave it away to someone who needed it more. Today, a beautiful gothic church in Harpswell is named for him. A granite monument there reads in part: “A beloved pastor and a preacher…a man of deep and generous piety, a lover of the sea and sailors and a sympathetic friend of boys.”

Admiral Richard Peary (1856-1920):

Before Peary staked his claim to be the first man to reach the North Pole, he was a young Bowdoin graduate working as a surveyor. In 1881, he bought Eagle Island for $200, calling it “The Promised Land.” The island became a treasured home for him and his family. It’s now a Maine Historic site and is listed on the National Registry of Historic Places. (See MBH&H #137 for more on Eagle Island.)

Peary’s cottage sits on a bluff, offering a striking view of Casco Bay; two stone “towers” function as retaining walls and safeguard his important artifacts. It was in the library here that Peary planned his Arctic excursions and wrote The North Pole (1909). His wife Josephine—they had met in a dancing class—was the author of The Arctic Journal (1893) among other works.

Jewel’s Story Book (1904) was part of a successful series by Clara Louise Burnham. Courtesy the author

Clara Louise Root Burnham (1854-1927):

Jewel’s Story Book (1904) was part of a successful series by Clara Louise Burnham. Courtesy the author

Clara Louise Root Burnham (1854-1927):

George F. Root, who composed “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! The Boys are Marching,” along with many other Civil War-era songs, built a summer home on Bailey Island for his family. His oldest daughter Clara likely spent every summer of her life at the gray-shingled cottage, which still stands behind Library Hall today. Writing as Clara Louise Burnham, she penned more than two dozen novels, including five that became silent films. In Dr. Latimer, A Story of Casco Bay, the charismatic Dr. Latimer and two sets of sisters speak in Maine accents and grumble about the winter: “Oh, it is fearful weather!… It has rained and then it freezes and then the sidewalks are ice and the wind blows.” Yet, one character speaks for them all: “When we feel that our forces have run low, that little spot in Casco Bay is a good place in which to gather a new supply.”

Clara Louise Burnham is important, too, because her niece, Esther (Tess) Root, married Franklin Pierce Adams, the author, columnist, and member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York during the 1920s and 1930s. Tess was beautiful and formidable—she would have been a CEO today, in the opinion of her daughter-in-law Judith C. Adams. Later, Tess repurposed World War II fortifications at the tip of Bailey Island for her summer home—before that, though, she introduced Harpswell to her close friend, the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay.

An aerial view of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Ragged Island, now conserved by Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Courtesy Maine Coast Heritage Trust

An aerial view of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Ragged Island, now conserved by Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Courtesy Maine Coast Heritage Trust

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950):

By the 1930s, Maine-born Millay was a rock star among poets. She’d won the Pulitzer Prize ten years earlier and had traveled the country reading to huge audiences. It was from the porch of Tess Root’s family cottage that she first set eyes on Ragged Island’s dramatic coastline. She and her husband bought it in 1933, and it quickly became a haven for her avant-garde friends—no swimsuits allowed.

Her famous 1947 poem “Ragged Island” emphasizes the island’s striking geography:

Edna St. Vincent Millay strikes a pose on a boulder along Ragged Island’s craggy shoreline. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Edna St. Vincent Millay strikes a pose on a boulder along Ragged Island’s craggy shoreline. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

“There, where those black spruces crowd

To the edge of the precipitous cliff…

And there is no driftwood there, because there is no beach;

Clean cliff going down as deep as clear water can reach.”

Paul (1897-1972) and Claire Sifton (1897-1980):

After Millay’s death in 1950, Claire and Paul Sifton, long-time Bailey Island summer residents, bought Ragged. Staunchly political, the pair wrote nearly a dozen plays that were produced in New York and London. Most memorable are 1931, the gritty story of a working man during the Depression (revived in 2012), and Midnight, which was made into a movie with Humphrey Bogart. The Sifton family still owns the island (with a conservation easement held by Maine Coast Heritage Trust) although Millay’s house and shed burned down in 1969.

The literary thread continues because their son, Judge Charles Sifton, married Elisabeth Sifton, a literary editor, author, and the daughter of famed theologian Reinhard Niebuhr. One of their sons, Sam Sifton, is the food editor for the New York Times.

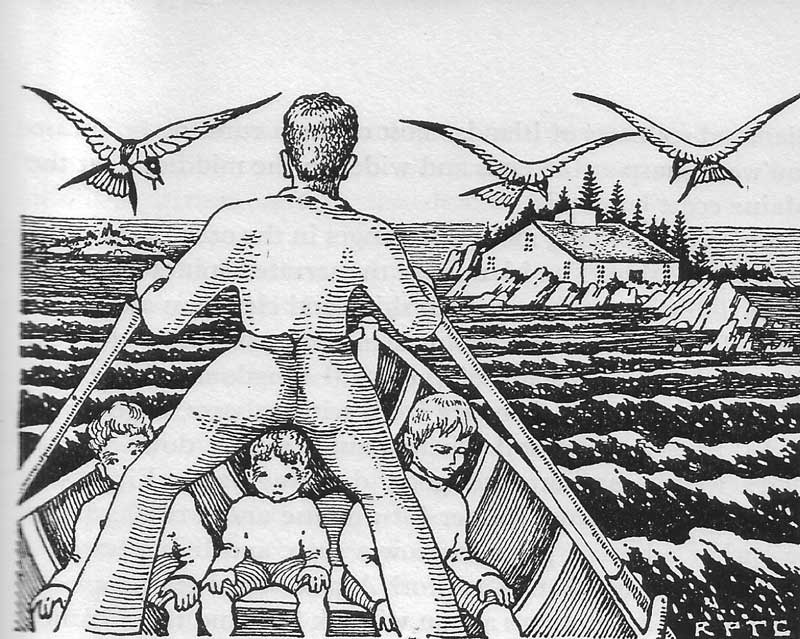

Robert P. T. Coffin was also an accomplished artist. This is a woodblock from Yankee Coast (1947). Woodcut from Yankee Coast, by Robert P. Tristram Coffin. NY: Macmillan Company, NY: 1947.

Robert P. T. Coffin was also an accomplished artist. This is a woodblock from Yankee Coast (1947). Woodcut from Yankee Coast, by Robert P. Tristram Coffin. NY: Macmillan Company, NY: 1947.

Robert P. Tristam Coffin (1892-1955):

Born on Pond Island (next door to Ragged), Coffin grew up on Sebascodegan Island (Great Island) in Harpswell in a house transported to the island by a schooner.

Coffin graduated from Bowdoin, then received a graduate degree from Princeton, was a Rhodes Scholar, and an English professor. He also wrote 13 volumes of poetry and an equal number of non-fiction books. He won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1936.

His writings are mostly passionate hymns to coastal Maine. His art, often featured in his books, shows an equally strong attachment. But he had a particularly deep affection for Harpswell: “I come of Island people,” he wrote in Island Living. “[Maine islanders] can trust themselves to be alone with their thoughts. And they can keep quiet for hours, for days. And years. And lifetimes.”

Dr. Carl Jung on Bailey Island in 1936. Courtesy of the Maine Jung Center and Beinecke Library, Yale University

Elizabeth Strout (b. 1956):

Dr. Carl Jung on Bailey Island in 1936. Courtesy of the Maine Jung Center and Beinecke Library, Yale University

Elizabeth Strout (b. 1956):

This brings us to Elizabeth Strout, a Pulitzer Prize winner for fiction in 2009 for the novel Olive Kitteridge. Although she was born in Portland, both sets of grandparents came from Harpswell, and she worked at the Bailey Store (now the Harpswell Historical Society Museum) as a teenager in the 1960s. She’d listen to the customers, especially the summer people, and imagine their lives. When asked in an interview with The New Yorker about her relationship with Maine, she replied, “That’s like asking me what’s my relationship with my own body. It’s just my DNA.”

There are others who also tasted the water in Harpswell and were inspired to write. These include John Greenleaf Whittier, who heard the legend of the Dead Ship of Harpswell at an inn there and told the tale in poetry. William Jasper Nicolls wrote Brunhilda of Orr’s Island, about a beautiful girl who catches the eye of a wealthy yachtsman, in 1908. Annie Haven Thwing, a Boston historian who summered on Orrs for more than 20 years, wrote a history of the island in 1925, and helped found the library. Invited by therapists to Bailey Island, psychiatrist Dr. Carl Jung gave seminars during the summer of 1936, which became the catalyst for the Jung Center in Brunswick; it still operates today. Margaret and Charles Todd wrote Beautiful Harpswell: The Neck and Its 45 Island Jewels in the 1950s. The novelist and University of Maine professor Elaine Ford lived for years in Harpwell, and the poet John Engels wrote about Harpswell’s Gun Point where he regularly rented a cottage. Finally, Janet Freeman Baribeau published her memoir in 2011, A Bailey Island Girl Remembers.

How to explain the role of Harpswell as a muse for this diverse group of writers? While early authors might be considered local colorists, others told stories that could not have happened quite the same way anywhere else. And all were inevitably affected by their experiences in the community. Perhaps Elizabeth Strout was right about the DNA, altered forever by the place.

Erika J. Waters, Ph.D., taught English at several universities, including University of Southern Maine, founded and edited The Caribbean Writer, and was a Fulbright Scholar to Finland. She’s a widely published writer and editor who lives in Maine and Florida.

The following assisted the author with research for this article. Thanks to David Hackett, President of the Harpswell Historical Society; Melinda Richter of Island Candy Company, Orrs Island; Sam Sifton; Elisabeth Sifton; Lydia Meers, Judith C. Adams, Richard Knox of Maine Coast Heritage Trust, and Freeport Public Library.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.