A Year in the Life of a Lighthouse

Betty Brown, seen here at age 89, and her husband “Dude” staffed the Pond Island Lighthouse in 1953 as twenty-two year olds. Photo by Ronald Joseph

Betty Brown, seen here at age 89, and her husband “Dude” staffed the Pond Island Lighthouse in 1953 as twenty-two year olds. Photo by Ronald Joseph

Betty Brown was distraught. Her husband, Pond Island Lighthouse keeper Alton “Dude” Brown, had rowed a mile to Phippsburg to purchase groceries and collect mail—tasks he tackled every third week. He had departed in sunshine but before he returned, a thick fogbank engulfed the lighthouse and much of coastal Maine. Located at the mouth of the Kennebec River, Pond Island Lighthouse was built in 1821 to mark the river’s west entrance. Seguin Island Lighthouse, two miles farther out to sea, had been built in 1796.

On that late summer day in 1953, Betty, then 22, stood inside Pond Island’s fog bell shed struggling to recall Dude’s step-by-step instructions for operating the bell, which would help guide him home. The two-ton bell, housed outside the shed, functioned like a grandfather clock: hand-winding a wheeled mechanism housed in the shed activated a descending weight, which released a heavy spring triggering a sledgehammer to strike the bell.

“Dude was rowing back to the island in fog as thick as pea soup,” recalled Brown, 66 years later. “But until I could get the fog bell striker to cooperate, he and ship captains would be courting trouble.”

The two-ton bell functioned like a grandfather clock. Hand-winding a wheeled mechanism inside the shed activated a descending weight, releasing a heavy spring, triggering a sledgehammer to strike the bell. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

The two-ton bell functioned like a grandfather clock. Hand-winding a wheeled mechanism inside the shed activated a descending weight, releasing a heavy spring, triggering a sledgehammer to strike the bell. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Her fears were well founded. Long before General Benedict Arnold and 1,100 Revolutionary War soldiers ascended the Kennebec River in September 1775, Native Americans struggled to navigate powerful currents colliding at the mouth. A thick fog could fatally complicate the situation. During the War of 1812, soldiers were stationed on Pond Island and nearby Fort Popham to prevent the British from entering this major waterway. After the war, Pond Island became a transfer station for passengers traveling by steamship to Augusta, Bucksport, and Bangor.

David Spinney, the island’s fourth lighthouse keeper in 1849, witnessed the capsizing of the Hanover, a Maine merchant ship returning to Bath following a three-year voyage to Spain and ports elsewhere. During the final leg of its homeward journey, the ship struck a bar in stormy seas and sank near Pond Island, losing all 24 crewmen. A dog, the ship’s lone survivor, swam ashore. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about the Hanover in The Pearl of Orr’s Island, published in 1861: “The story of this wreck of a home-bound ship just entering the harbor is yet told in many a family on this coast.” For nearly a hundred years, a copy of the book was kept in the Pond Island Lighthouse.

Aware of that tragedy, Betty’s concern for her husband bordered on outright panic. “I did everything I could think of to start that darn bell,” she remembered, “but it refused to work. And wouldn’t you know, as soon as I ran to the lighthouse to attend to my crying six-week-old baby Michael, the bell miraculously began clanging.” Dude had rowed past the island, but reoriented the 16-foot dory after hearing the bell. Approaching the island, he was guided to the slipway on the west-facing shore by the sound of crashing breakers on ledges below the bell house.

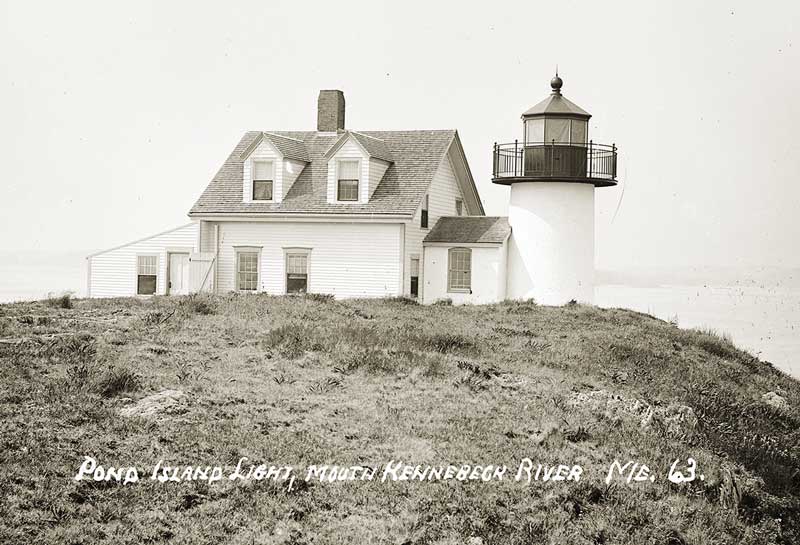

Pond Island Lighthouse was located at the mouth of the Kennebec River, about a mile from the mainland. Lighthouse keepers rowed ashore every three weeks to collect mail and acquire provisions in Phippsburg. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Pond Island Lighthouse was located at the mouth of the Kennebec River, about a mile from the mainland. Lighthouse keepers rowed ashore every three weeks to collect mail and acquire provisions in Phippsburg. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

The Browns had first arrived on Pond Island not a month earlier. Huddled beneath the rounded hull of a Coast Guard boat with a baby in a bassinet, Betty became seasick on the ride out. “We accepted the lighthouse keeper’s job,” she said, “because it allowed us to live together for the first time. Although I felt nauseous, I was very happy being reunited with my husband.” Dude’s previous Coast Guard jobs had forced the couple to live apart. Trained as a nurse in a Lewiston hospital, she arrived on the island with a suitcase filled with medicines, bandages, penicillin, and hypodermic needles. “I was prepared,” she said with a smile, “to handle everything from suturing wounds to treating illnesses.”

Contrary to its name, 10-acre Pond Island is pond-less. Covered with shrubs, rocky outcrops, and sloping sparse fields, “the island,” wrote lighthouse keeper Spinney, “lists to the starboard like a hobbled ship.” Its lack of fresh water prompted Samuel Rogers—lighthouse keeper in 1823—to petition the government to dig a well or install a cistern. “I am the keeper of the Light House on Pond Island,” he wrote to the federal Lighthouse Establishment Department. “I suffer great inconvenience on account of having no means to obtain fresh water but by transporting it from the mainland. It is usual, I am told, to have a well or Cistern on the Islands where Light Houses are placed.” The government authorized construction of a cistern.

“The cistern was in the cellar,” recalled Brown. “It collected water from the roof of the keeper’s house. We were judicious with its use, the cistern being our sole source of water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and washing clothes.” An old hand pump in the slate kitchen sink drew the water up from the cellar. Their domestic water was heated in a cast iron pot on a large wood-burning cookstove retrofitted to burn coal. “Once a month,” she added, “the cistern had to be drained and disinfected on account of gulls and other sea birds defecating on the roof. We timed the task with a wet weather event to allow the cistern to quickly refill.”

The two-story keeper’s house was heated by a coal-burning furnace. Twice a year, a Coast Guard boat delivered 100 or so large bags of coal for storage in the basement. The house had no electricity or indoor plumbing. “Our outhouse was 20 steps from the back door,” she said with a laugh. “Ten if you had to hurry.” Kerosene lamps brightened rooms sufficiently to read books. “Imagine my thrill discovering a gasoline-powered washing machine—it made washing a dozen diapers a much easier daily chore,” she recalled.

Winter storms often sent spray from crashing waves onto the leaky second-story windows of the Pond Island keeper’s house. From November until April, Betty Brown kept a mop and pail in her upstairs bedroom. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Winter storms often sent spray from crashing waves onto the leaky second-story windows of the Pond Island keeper’s house. From November until April, Betty Brown kept a mop and pail in her upstairs bedroom. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

For posterity, Betty kept a copy of Dude’s job description: “Lighthouse keepers must keep alert, keep watch, keep clean, keep calm, keep accounts, keep house, keep track of time, and always try to keep healthy.” Lighthouse keepers, the Coast Guard advised, should have a wife and family to help share duties. Betty assisted her husband when the baby was asleep. “Dude lit the lighthouse kerosene lantern each day at dusk and extinguished it at dawn,” she remembered. “When I awoke at night to tend to our baby I’d check to see if the lighthouse light was still on. Dude got up during the night too to make sure the lantern’s wick remained lit.” The lantern was housed inside a Fresnel prism lens, an ingenious 1823 invention of French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel. Universally known as “the invention that prevented a million shipwrecks,” Fresnel lenses collected, bent, and aimed light from the kerosene lamp. In 1855, when the first Pond Island Lighthouse was replaced with a taller one, a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed. The 56-inch diameter lens could project a beam of light equivalent to 80,000 candles a distance of 16 miles.

Black soot accumulated on the lens, requiring daily cleaning, as did the lighthouse’s windows. “The glass had to be spotless,” Betty stressed. “Ships entering and exiting the Kennebec River relied on the island’s bright beacon of light.”

“Dude grew up in rural Maine and could fix anything,” she said. “Maintaining the island’s seven buildings tested his skills but he enjoyed the challenge. Painting, though, was our most time-consuming chore. Salt air and salt water takes a toll on buildings and boats. It seemed like we were constantly applying white paint.” Storms often sent sheets of saltwater spray to the second story bedroom windows. “The windows leaked so badly during winter storms,” she recalled, “I kept a mop in our upstairs bedroom.”

As with all Maine lighthouses, the oil house—where kerosene and gasoline containers were stored—was painted red and situated several hundred feet from the lighthouse and keeper’s house to reduce the risk of an explosive fire spreading to the main buildings.

In 1954, following the end of the Korean War, Dude’s three-year stint with the Coast Guard ended. He was replaced by lighthouse keeper Bruce Reed and his young family. Betty and Dude left Pond Island in 1954, purchased an old farm in central Maine, and grew and sold a variety of apples.

“I was heartbroken the day we left Pond Island,” Betty reminisced. “Contrary to conventional thinking, living on the island wasn’t a hardship. We loved living on the small, remote rocky island. On a clear day you could see Seguin Island and well beyond it to the open sea. Lobstermen frequently delivered free lobsters as a way of thanking us for operating the lighthouse. Even today I pinch myself thinking how fortunate I was being the wife of a lighthouse keeper. Living on the island was a marvelous chapter in our lives.”

Ronald Joseph is a retired Maine wildlife biologist. He lives in central Maine.

WEB EXTRA

In a 1923 poem, Mrs. Elmenia P. Lurvey, a lighthouse keeper’s wife on Wood Island, Biddeford Pool, captured the work of all Maine lighthouse keepers.

I am sitting beside this billowy ocean,

And gazing on naught, but the sea and the sky;

The crystal waves roll with an unceasing motion,

As they rush on the seashore, in foam breaking high.

We three are alone on this desolate island:

Alone with my husband and Wilbert, his son.

He is lightkeeper here on the Wood Island Light Station,

When daylight is ended his work is undone.

For, when nearly sundown, he ascends the high tower,

He lights the big lantern that gleams through the night;

For the sea-faring sailors, roaming over the ocean,

Who patiently watch for the red beacon light.

When the clock points to midnight, he again mounts the tower,

To wind the machinery revolving the light.

He carefully watches till its beams shine forth brightly,

Then wakefully slumbers through the rest of the night.

At the dawning of sunrise he starts for the tower,

To put out the light, tidy up for the day.

There’s enough work to do to keep things running smoothly,

It is work while the day lasts, not much time for play.

More especially now, since the burning of soft coal,

Keeping everything covered with black, smutty dust;

It is useless to growl at the U.S.A. government,

But shovel the coal and in Uncle Sam trust.

Both outside and inside the tower must be painted,

The stairs painted too, winding up to the light;

The dwelling inside must be painted and varnished,

Outside every building is all painted white.

In sea fog and snowstorms he enters the tower,

To mind the big weight so the clock may run well;

For the benefit of seamen approaching the harbor,

Who anxiously listen for the sound of its bell.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.