Welcome Downeast

The Towns, the Bays, the Mountains

“In November the trees are all standing, all sticks and bones. Without their leaves, how lovely they are, spreading their arms like dancers. They know it is time to be still.”

—Cynthia Rylant

Dear Friends:

There appears to be a bumper crop of acorns this year. In many places the ground is nearly covered with them, brought down from our towering red oaks, Quercus rubra, by recent wind and rain. This is good news for crows, blue jays, wild turkeys, gray squirrels, raccoons, white-tail deer, and even some ducks, all of whom include acorns in their diets. Studies have shown that over the course of the winter blue jays can remember the locations of thousands of acorns they have buried as far as two and a half miles from where the nuts fell. This is impressive, especially when you consider that a lot of us can’t even remember where we left our keys. Of course, even a clever bird can’t remember every single acorn he has buried, and that is the way the forests of tomorrow are planted.

The year-round creatures are not only tucking away food supplies, but also finding warm places to stay during the cold months. I’ve been stacking wood from a pile that was dumped in the dooryard three weeks ago. Near the bottom I found a soft, round squirrel’s nest, freshly built. I felt bad wrecking Little Red’s shelter, but he’ll probably move right into the woodshed and find it even warmer there. We sometimes see big-eyed field mice in the house this time of year, too, and why not? It’s warm and dry with plenty of food and places to hide.

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Natural events, November

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Natural events, November

Blue jays and cardinals—birds, that is, not ball-players—strut around under the bird-feeders like toy soldiers from the Thirty Years’ War, in plumed helmets and colorful coats. Blue jays are related to crows and can imitate human voices. They love to collect shiny things and can fashion crude tools. They’ll even mimic the calls of a red-tailed hawk to frighten other birds away from a choice food discovery, but they will also give a warning shout to all the other birds at the sign of any intruder. Jays are omnivorous to a fault, eating anything from nuts and seeds to mice and the eggs of other blue jays.

Cardinals used to be considered a southern bird but are now found from southeastern Canada to New Mexico. They are primarily seed-eaters and are highly territorial. Cardinals are related to the finches, as a comparison of their beaks will show. They can shell a sunflower seed in the twinkling of an eye with their large bill alone. Even a big blue jay can’t do that. They take the seed up into the tree, hold it in one foot, and hammer it open with their pointed beak.

Field and Forest report

Frost steals in after dark silently freezing the birdbath, speckling the green grass with sparkling white, pushing up crystal tusks from the wet ground, and putting a crunch in every step. Then, around mid-morning as the weak sun rises ever so slowly above the treetops, a cool mist curls up from fence rail and shed roof, the faint sound of dripping water is heard, the grass turns green again and the ground becomes soft and yielding underfoot. Freeze, thaw, freeze, thaw, freeze, thaw: this is the ancient and powerful hydraulic hammering that splits old boulders and older mountains ever smaller through ages upon ages until they can be picked up by any man with a good pair of hands and a strong back to add to an old stone wall—only to be thrown down by the frost once more as soon as he turns away.

Mountain report

As I was heading up the trail on a mild morning, it seemed that the mountain suddenly began talking to me. A sudden rush of words came pouring into my head, bringing new ideas and new perspectives on things. It was like listening to someone far wiser than myself, gently but firmly teaching what I needed to know.

At the risk of making you think your commentator has really gone around the bend this time, I will say that this has happened to me before. Maybe it has happened to you, too. This time, the mountain was expounding on the theory of evolution whereby the organisms that survive and thrive are those that best adapt to their environment.

“But what is the environment?” said the mountain. “It is not a thing. It is everything above and below, near and far, active and inactive, living and non-living, seen and unseen. It is made up of all weather, every stone, every grain of sand, every cloud or drop of water, every living thing. Any change in one calls for change in all. The scene is not of a bloody battle for survival with only a few winners so much as it is an age-old worldwide creature chorus swelling in song with every member constantly tuning its pitch and shading its volume to every other, to create the most pleasing and beneficent harmony, embracing and enhancing all, ever richer. Some voices sing high so others sing low, some are silenced while others are added; some rise while others fall, some sing the descant while some hum the bass, some die so that others can live. It is the music of the spheres, and the director is also the composer who hears from within and swoons with delight.” So the mountain seemed to say that day.

Thanksgiving

Since the beginning of time, giving thanks has been a regular observance among us. Thanksgiving is also a socially, economically, and ecologically healthy practice, because gratitude mitigates greed. We do not destroy what we appreciate. We do not waste or ruin what we are thankful for. We do not hoard what is not ours. All ancient people knew this, and so universally expressed thanksgiving in their spiritual practices. What we call the First Thanksgiving was not the first at all, but just one more of millions. This is not simply some lofty sentiment. Gratitude is hard-wired into the human soul. That is how humans lived sustainably on the earth for millions of years. And that is why a simple meal, eaten gratefully, is far more satisfying than the richest feast, eaten mindlessly.

Natural events, December

One of the delights of the first snow is that it lays down a parchment upon which the creatures can inscribe their lively motions over the course of the day, a manuscript that can be read and interpreted by the careful observer.

The gray-brown winter coats of the white-tailed deer are getting shaggy, and a good thing, too, because it’s the only winter coat they have—and no hat or boots. Our black bears have mostly “gone to ground” by now. They have loaded up on wild berries and beechnuts to put on a layer of fat that will sustain them through their long winter’s nap, and they have denned up in a cave, or under a blow-down, or in a hollow log for the next several months. Chipmunks are also burrowed in and are true hibernators, though they do wake up now and then. Other small mammals like squirrels, skunks, porkies, weasels, and fisher cats do not hibernate but rest in their burrows during bad weather and emerge to forage on more forgiving days.

Those of us who retreat inside during these cold days throw another log on the fire and put the pot on to simmer, the smoke rising straight up the chimney. Finches slide along the frozen surface of the birdbath-turned-tiny-skating-rink. Deer dance daintily while crows and ravens mutter above on newly snow-laden branches.

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Rank opinion

Illustration by Candice Hutchison

Rank opinion

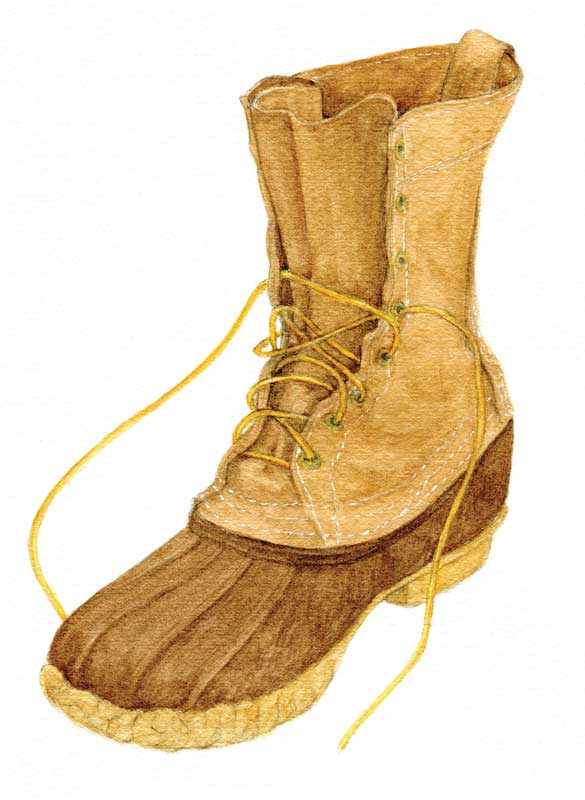

Amid the man-made stuff, it seems that a certain brand of rubber-bottomed, leather-topped duck boot which has been made in Maine for more than 100 years is enjoying a surge of popularity among urban millennials and others—a kind of retro outdoor chic, if you can imagine it. So many of them want the boots that the company had to expand its operation to meet the demand. As might be expected, used boots with the patina of age are sometimes going for a lot more than a new pair. It occurs to your commentator that this might offer the opportunity for some of us to make some ready cash. My better half and I each have a pair of these boots with high tops (a style they don’t even make anymore) with a patina of 40-plus years that ought to be worth something. But on the other hand, they’re mighty good boots. I’d hate to part with them, even though we wear them only on ceremonial occasions. Maybe we’ll just pass them on to the grandkids when we go for the long sleep.

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Gordon Bok: “When the deer has bedded down and the bear has gone to ground, And the northern goose has wandered off to warmer bay and sound… If I had a thing to give you, I would tell you one more time, That the world is always turning toward the morning.”

That’s the Almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Yr. mst. humble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall.

Rob McCall lives way downeast on Moose Island. This almanack is excerpted from his weekly radio show, which can be heard on WERU FM (89.9 in Blue Hill, 99.9 in Bangor) and streamed live via www.weru.org. Reach Rob via email at awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.