Once Trash, Now Treasure

A sign underwater points to the past

On a drainer tide, in the bright cold of winter, I went for a cruise on my standup paddleboard in Camden Harbor. I had it all to myself, if you don’t count the winter ducks and a lone harbor seal. In my thick wetsuit I stood on my thin board in the low morning sun and paddled out, my warm breath visible and my gloved fingers a little numb.

The stillness of the harbor in winter is different from the bustle of summer. Gone were the rafted transient yachts at Wayfarer and the town docks. Most of the harbor floats were empty—or even gone, stacked high and dry on shore.

Seawater in winter can be especially clear. On this bright morning, it made for a sense of flying, as I glided over the surface. The silty bottom passed by underneath and my mind wandered back to memories of years of diving in this harbor. There was the time of fetching a winch handle someone had dropped overboard. Or the unwinding of lobster gear from a prop shaft.

Just then I noticed something shimmer in the otherwise uniform grayness of the bottom. A curve of bright orange, the edge of what looked like a circle, jutted from the stones and mud, about 10 feet out from the pilings of the wharf, in about five feet of water. I crouched on my board and stared down. With the possible exception of sunsets, that color does not exist in nature. It was probably trash. And yet, I wondered if there might be some treasure down there.

I took a look around to see if anyone was watching—not because I was considering anything untoward, but more out of private discomfort. I was already aware that some people, including my wife, thought it was sufficiently strange to be paddling alone in the harbor at this time of year. I did not want even the imaginary burden of explaining what I was doing.

Floating over the site, I lay my paddle on the board and slid into the water. The biting cold seeped into my wetsuit along the seams. My face hurt as I went under and down, holding my breath. On the bottom I grabbed onto the orange edge of whatever it was. And I pulled. I had to tug several times, and had to come up for air twice. The clarity in the water was gone as my tugging stirred up mud and silt. I kept at it until I finally came up with a sign from the past.

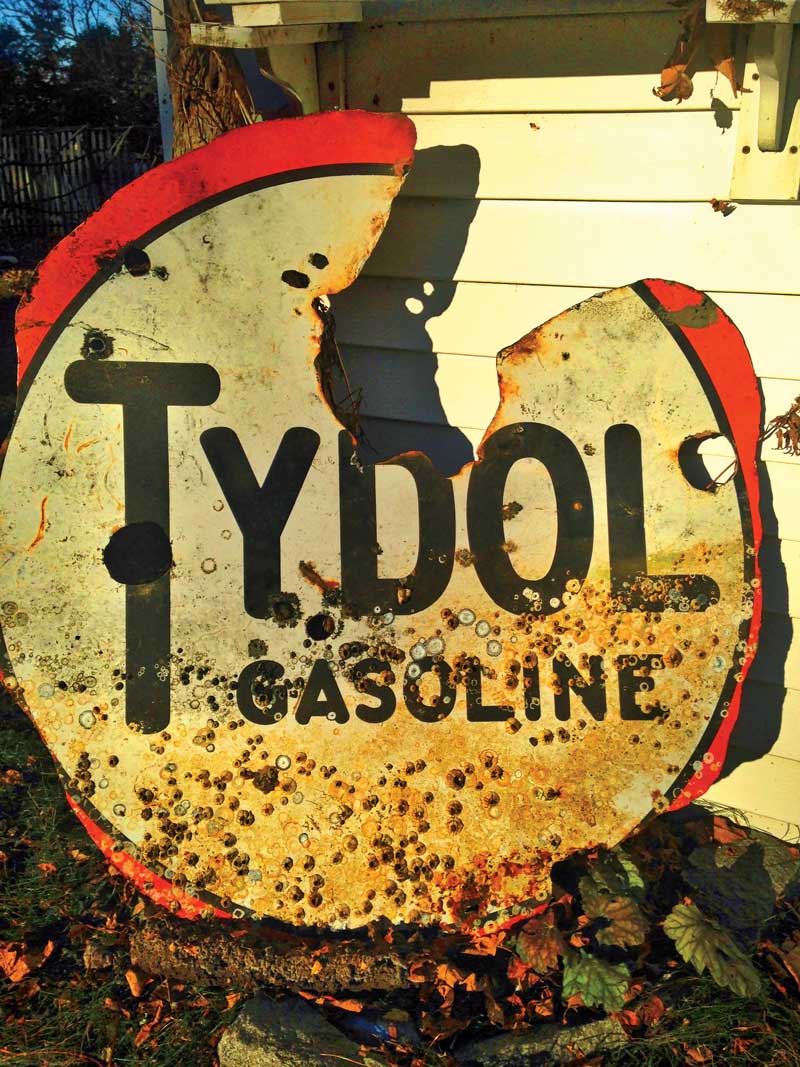

Surely it was trash when it was tossed overboard, but decades underwater gave this sign a precious patina. Photo by Jeffrey C. Lewis

Surely it was trash when it was tossed overboard, but decades underwater gave this sign a precious patina. Photo by Jeffrey C. Lewis

Literally, it was a sign.

The sign was big. It was round, mostly; rusty steel, with a partly shiny ceramic coating. An orange band rimmed a white center, with black letters in a rounded font from a different time. It said TYDOL in big letters. GASOLINE in small.

My standing weight pinned it to the deck as I paddled tenderly back to shore, trying to keep it from sliding off and back to the bottom. If I lost it, I wasn’t going back.

A Google search in my warm kitchen an hour later told me what I had. Tydol Gasoline was a product of the Tidewater Petroleum Co., which thrived in the 1920s and 30s. This sign likely had been underwater my entire life. Before the Second World War. Before Korea, and Vietnam, and the Cold War and the Civil Rights movement, and the space program, before Watergate and Y2K and before any understanding that the carbon cycle would eventually affect the climate of the whole world, this sign lay in the mud in Camden Harbor.

For all the years that the sign was underwater, and long before, men have gathered each morning to swap news at one downtown spot or another. These days, Main Street’s Camden Deli is where the Elite Coffee Group congregates. There are more endearing names for this eclectic and crusty band of brothers, but whatever they are called, or call themselves, they are an institution that has counterparts in small town coffee shops up and down the coast. Through a nepotistic connection, I enjoy a seat at the table whenever I show up. Sometimes it’s the easiest way to see my old man, to get the conflicting news of the day about town politics, or to find the answer to an historical question that I could find nowhere else. I knew the coffee group would know the story behind the sign.

When I described what I’d found in the harbor, there was hardly a pause. The 70 or 80 years, represented by mud and barnacles, might as well have been yesterday afternoon.

“Oh sure, the old TYDOL gas dock. That was before TYDOL became Enco, and before Enco became Exxon. There was a fuel dock and marina on that side of the harbor then, where the condos are now. That sign probably came down before the war, probably in the 1930s. They must have just tossed it into the water—the easiest way to dispose of it when its time was done.”

I am glad the Tydol sign was tossed in the harbor. I am glad that I found it. I am glad to hear the story of where it was and how it (probably) got there.

The cheerful assurance of the normalcy of my find in the voice of my father’s friends gave me an inexplicable feeling of reverence and connection. It was just a relic, a piece of unwanted trash. But the time it spent on the bottom of the harbor and the way that it came into my world infused it with charm and nostalgia. Its connection to the past gave it a treasure-like patina, enhanced with rust holes and barnacle scars. A century from now, what will a winter day on Camden Harbor look like? And what might be found there by a future wanderer?

I can hardly know, any more than the person who tossed this sign could have imagined that one day, a person in a body suit made from petroleum rubber, standing on a surfboard designed in Hawaii, built in Taiwan, and bought in Maine, would spy this sign in the bottom of the harbor, and be curious and nuts enough to try to pull it up.

When I look at it now, hanging from an old nail on the wall of my backyard shed, these thoughts make me wonder, and smile.

Jeffrey C. Lewis lives on the central coast of California, but midcoast Maine is home, with a seat at the Elite Coffee Group.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.