Calvin Beal 42

Veteran lobsterman moves farther offshore

Photographs by Brian Robbins

One of the many things David Cousens likes about his 42' Sea Wolf is her sailing attitude: “She basically just lifts all over when you hit the throttle—never gets too high in the bow.”

One of the many things David Cousens likes about his 42' Sea Wolf is her sailing attitude: “She basically just lifts all over when you hit the throttle—never gets too high in the bow.”

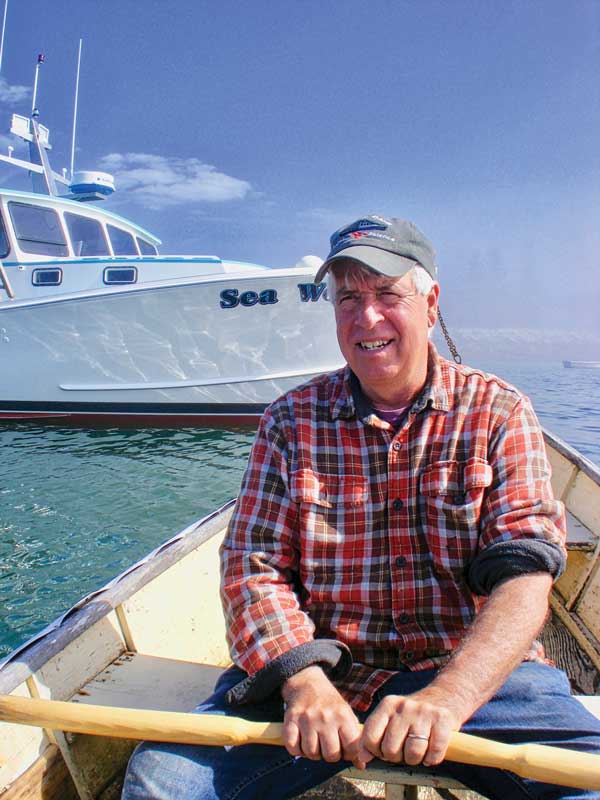

David Cousens was 10 years old when he began his lobstering career.

At the age of 60, Spruce Head, Maine, lobsterman David Cousens was at a crossroads of sorts in 2018. To start with, he’d just stepped down as the president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, after 27 years of fighting the good fight for the industry in meeting rooms from Washington, D.C., to the Canadian Maritimes—and wearing out a slew of pickup trucks in the process.

David Cousens was 10 years old when he began his lobstering career.

At the age of 60, Spruce Head, Maine, lobsterman David Cousens was at a crossroads of sorts in 2018. To start with, he’d just stepped down as the president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, after 27 years of fighting the good fight for the industry in meeting rooms from Washington, D.C., to the Canadian Maritimes—and wearing out a slew of pickup trucks in the process.

“There were plenty of 50,000-mile years,” he said. “And there were plenty of flat-calm days where I was up in Augusta in a hearing room rather than down the bay... but it needed to be done.”

Cousens started lobstering out of an outboard when he was 10 years old and has worked hard ever since. He took enough time off to earn a teaching degree, but was back on the ocean once he graduated. Over the years he and wife Lori raised a family together (they have three grown sons, all with their own lobstering operations), dealing with not only a fisherman’s schedule, but an MLA president’s schedule as well.

There are plenty of people who would reach that point in life and think it was time to kick back a little and enjoy life, perhaps do a little traveling or get serious about their golf game.

David Cousens? He moved his lobstering operation out to Criehaven Island and built a bigger boat.

Look up Criehaven and you’ll see phrases like “unorganized territory” and “unofficial township” describing the 440-acre nubble lying just south of Matinicus—which itself is a 20-mile ride offshore from Rockland. Depending on the chart you’re looking at, you might not even see the name Criehaven: Ragged Island is the more official moniker.

So why did Cousens move farther offshore at an age when many of his peers start to think about heading in the other direction?

He’d considered buying property out on Criehaven back in the late 1980s, but couldn’t make it work financially. The lure wasn’t just that it would be a sweet place to spend some time in the good weather months, it was also the fishing bottom that came with property ownership. With a berth on Criehaven Island, you have the right to fish in company with a small group of other lobstermen who own land there (this past summer there were eight boats total).

“I like it off there; there’s no bullshit whatsoever,” Cousens said. And that pretty much sums up the man.

Back in 1996, Cousens had the now-defunct Young Brothers shop in Corea, Maine, build him a 40-footer, which stood him well for 24 lobstering seasons.

But when you cast off from the mooring out on Criehaven, you’re basically offshore, and he soon found that he needed something different.

“My 40 was a great boat, but she had a cored hull,” he said. “She was light, and you could feel it. I put the word out with the MLA guys that I was looking for something a little larger and heavier, nothing real big, just stable.”

He figured he’d end up with something used; but a phone call from his friend and fellow MLA member Dwight Carver down on Beals Island changed all that.

Sea Wolf finisher Calvin S. Beal and his father, designer Calvin Beal Jr.

Sea Wolf finisher Calvin S. Beal and his father, designer Calvin Beal Jr.

Back in 2016, Calvin S. Beal, son of well-known designer/builder Calvin Beal Jr., finished off one of the 42'x15' models from SW Boatworks in Lamoine that bears his father’s name. Young Calvin’s 42' Vondelle Lea was a streamlined lobster machine: a single-station setup with modest horsepower (a 550-horse Nanni) and economical to run.

The no-nonsense setup appealed to a lot of people, and by the end of his 2016 lobster season, young Calvin had sold that 42 and ordered another one. That pattern repeated itself in 2017, 2018, and 2019. By the time each of the similarly-finished 42s was sold, the next hull in line was often already sitting in the dooryard.

The plan for the fifth Calvin Beal 42 was different, however: young Calvin was going to size down for the 2020 season and finish a 34-footer for himself. This past winter’s 42 would be finished for the first buyer who came along.

That’s when Dwight Carver, who lives just down the road from Calvin Beal’s shop, gave Cousens a call.

Young Calvin’s standard package price for his 42s has included an open tailgate and an aluminum trap rack along the port side. “I told Calvin I didn’t want the stern cut out and I didn’t want a trap rack,” Cousens said. “But I did want a crash bulkhead, a storage compartment under the floor, and the trap hauler built up the way I always had it on my old boat.”

“‘Can you do that for the same price?’ I asked him.

“‘Yep,’ he said.

“‘Then we’ve got a deal,’ I told him.

“I shook Calvin’s hand, gave him a check, and I only went down maybe four times while he was building it. There was no need to. He knows his stuff.”

A view of Sea Wolf’s spacious work deck and single-station wheelhouse.

A view of Sea Wolf’s spacious work deck and single-station wheelhouse.

Kennedy Marine Engineering in Steuben provided the power package for the 42-footer: a 550-hp N9 Nanni backed by a ZF-305A 2.03:1 marine gear. “Both young Calvin and his father said I’d go just as well with 550 horses as I would with 750 with the boat balanced off right, and they were right,” explained Cousens.

With a 30"x28" 4-bladed Michigan prop from Nautilus Marine in Trenton providing the kick back aft, Sea Wolf tops out at 27 knots. Throttling back to 1900 rpm (the Nanni is a 2500-rpm engine) yields an 18-knot cruise with a fuel burn of just over 14 gallons an hour.

The extra speed (a 45-minute cruise out to Criehaven from Spruce Head compared to an hour and a quarter in the old boat with a 12-knot cruise) is one thing. Equally important was the additional stability.

David Cousens wanted his trap hauler set up the same way he had it in his old boat. “The position of the control handle, the fairlead, the guard— everything worked great for 24 years,” he said. “No need to reinvent the wheel.”

David Cousens wanted his trap hauler set up the same way he had it in his old boat. “The position of the control handle, the fairlead, the guard— everything worked great for 24 years,” he said. “No need to reinvent the wheel.”

“I’ve been out in weather I wouldn’t have fished in my old boat,” Cousens said. “I was setting traps in the spring and the first time I took a sea side-to I thought, ‘I’m going to roll these things off the boat,’ but no. She rolled, but it was an easy, slow motion—and that’s when I knew I’d done the right thing.

“It’s a great boat.”

And as everybody knows, a great boat beats a great golf game any day.

A former offshore lobsterman, Brian Robbins is senior contributing editor for Commercial Fisheries News when he’s not writing about music or riffing on various things with strings in the Horseshoe Crabs.

Calvin Beal 42

LOA: 42'

Beam: 15'

Transom: 14' 2"

Designer: Calvin Beal Jr.

Hull Builder: SW Boatworks

Finisher: Calvin S. Beal

Power: Kennedy Marine Engineering

Prop: Nautilus Marine

How the Calvin Beal 38 begat the Calvin Beal 42

SW Boatworks’ shop manager Will Duffy (left) and shop owner Stewart Workman inspect a lengthened hull.

It was a matter of demand (first) and supply (in response), according to SW Boatworks’ Stewart Workman, whose yard in Lamoine builds the full line of models that bear designer Calvin Beal Jr.’s name (as well as the well-known Young Brothers hulls designed by Ernest Libby).

SW Boatworks’ shop manager Will Duffy (left) and shop owner Stewart Workman inspect a lengthened hull.

It was a matter of demand (first) and supply (in response), according to SW Boatworks’ Stewart Workman, whose yard in Lamoine builds the full line of models that bear designer Calvin Beal Jr.’s name (as well as the well-known Young Brothers hulls designed by Ernest Libby).

“I had a lot of people who loved the Calvin Beal 38,” Workman said, “but they wanted to be able to carry another tier of traps.”

A number of customers asked about simply adding 4' to the stern of the 15' wide Calvin 38, but both Workman and designer Beal felt that approach would be detrimental to the hull’s run.

“It would be the easy way out, but it wouldn't sail right,” said Workman.

He finally consented to tackle the project when Milbridge lobsterman Eric Beal put down a deposit on the first Calvin Beal 42, sight unseen, agreeing to allow his hull to be used as the plug for a new mold.

Working with guidance from Calvin, Workman and crew began the process by laying up a 38-footer, and building a couple of steel cradles.

“When you cut a hull in two, it’s easy for things to go wrong,” said Workman. “We bolted the 38 hull right into the steel cradles so that when we cut her in half she wouldn't lose her shape.”

Cut her in half? Yes, cut her in half.

Workman added the extra 4' right in the middle of the hull, paying heed to Calvin’s advice along the way. It was a process of “snipping a little bit here” and “cutting a little bit there,” said Workman—but the day came when the hull was ready for Calvin Beal’s final inspection before fairing.

“He got down on his knees, squinted one eye, and said, “It looks pretty darn good to me—you got her.”

—Brian Robbins

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.