The Fine Art of Plugging Leaks

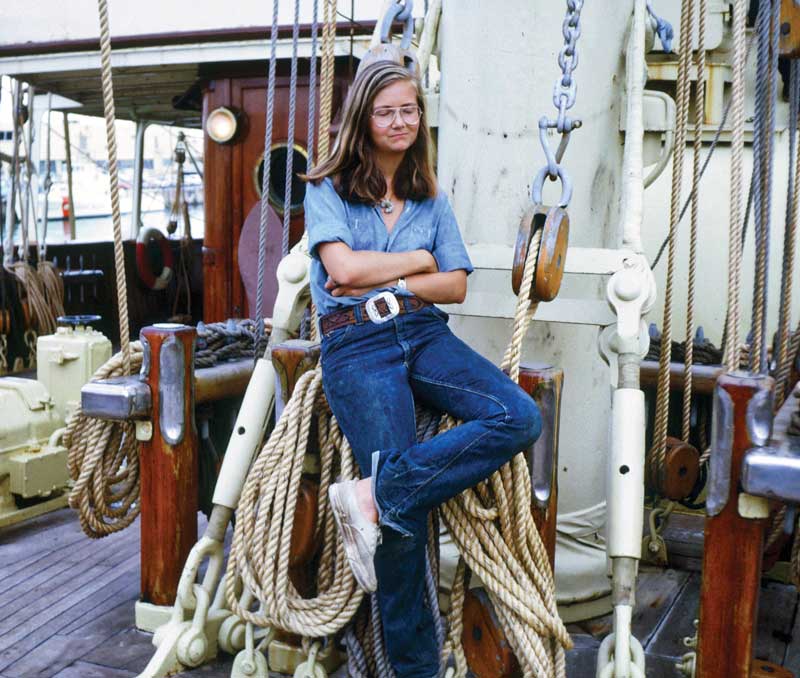

Images courtesy Helen Garber At seventeen, Elizabeth Garber was a sarcastic bookworm who’d never dreamed of going to sea, but her dad sent her anyway.

At seventeen, Elizabeth Garber was a sarcastic bookworm who’d never dreamed of going to sea, but her dad sent her anyway.

Before dinner Pogo said, “Come see what I’m doing in the carpentry shop.” I followed him down from the foredeck into a short, dark hallway to an open door. Pogo worked at a massive bench, shaving curls of wood off foot-square blocks to form a sharp point on one side.

“What are these for?”

“In case our ship springs a leak.”

I was confused. “How could our ship leak? Isn’t the metal hull thick?”

“These are plugs, in case a sea chest springs a leak.” The sea chests were the large metal grids where the ship’s engines had a steady inflow of sea water. “The opening where water comes into the ship is vulnerable, and our captain wants to be prepared for an emergency.”

Pogo drew a two-handled blade across the wood. “It’s a spokeshave. I love the wood curls.” I picked up a handful. Pogo said, “The first time I was ever in a boat there was a hole in the hull.”

“What happened?”

“I was maybe four, when my dad bought an old sailboat, but I don’t think he really knew how to sail.” One summer day, he and his two older sisters and parents crammed into the little boat and headed out into the bay off Bar Harbor. They had enough breeze to get to the middle of the bay but then the wind died down.

Pogo glanced at me with a quirky smile. “Suddenly about four inches of water rose in the boat. Mom panicked but Dad said, ‘Oh Jean, you worry too much.’” Pogo’s eyes widened. “Then a whoosh, and the water gushed up to our knees. A puff of wind, and we ever so slowly capsized.”

I gasped, imagining him as a little kid out in cold water far from shore. “Could you swim?”

He shook his head. “Fortunately, my life vest worked and I bobbed about. But I panicked.” Luckily, his dad was a strong swimmer who pushed him up on the upside-down boat. It wasn’t too long before a lobsterman arrived, brought the family aboard, and wrapped them in blankets. “He attached a line to the sloop, gunned the engine, and the sailboat slowly righted herself. I’ve been afraid of swimming in deep water ever since.”

I said, “I’m afraid of deep water, and I’ve never been on a sinking ship!”

I sat on a stool and watched Pogo work. He told me how he and his dad went to the boatyard. “Even though I was only four, I learned with my dad how to fix the hull and caulk the boat.”

Everyone—students, teachers, and crew—climbed the rigging, even those who were terrified of heights.

Everyone—students, teachers, and crew—climbed the rigging, even those who were terrified of heights.

He walked around the carpentry shop. “We used a tarred hemp caulking strand. Here, smell it.” He stuck a variety of objects and cans under my nose as he described the work they did on that sloop. Linseed oil putty. Nautical paints. He grinned. “When I was little, the smells were intoxicating. Whenever I sniff these smells now, I’m transported back.”

The whistle called us to dinner.

The captain had been wise to have these blocks prepared. A week or so later, I woke up on my bedding on deck in the middle of the night to the noise of students running by. I watched Karl, our scuba teacher, as he climbed over the railing and walked, dripping wet down the deck. I called out to him, “What’s going on?”

He said, “An intake valve gave way, meaning there’s a hole in the hull and water’s pouring in.” He fussed with his scuba valve. “When I got up on deck, two students had hauled a single mattress out on deck. I asked, ‘What the hell are you kids doing?’ One explained, ‘You need to swim down to the sea chest screen with this mattress. We think the suction from the hole in the hull will suck in the mattress and stop the leak.” Karl sat down on the deck and took off his flippers. “It sounded crazy but it worked.”

“You mean the leak is stopped by a mattress?”

“I guess they are fixing it down below now.” He rinsed off his gear.

I ended up going back to sleep on deck. Early the next morning, Pogo came by and sat down next to me.

Pogo laughed. “What a night! A boy shook me awake, saying, ‘We’ve got a leak. Get one of the sea chest plugs down to the engine room right away!’ Did I run! By the time I raced down the ladders in the engine room, water was surging around their feet.”

I gasped. “What did you do?”

The crew lined up at morning “muster” for job assignments: scrubbing decks, life boat rowing, splicing ratlines.

The crew lined up at morning “muster” for job assignments: scrubbing decks, life boat rowing, splicing ratlines.

Pogo shrugged in his humble way. “Because Chief Engineer Alfonso is a big guy, and I’m scrawny, he sent me crawling in where the water was gushing. I pushed the wooden plug as hard as I could, but the pressure from the leak kept shooting the plug back at me. We were desperate, and I was soaked and cold. But suddenly the water slowed to a trickle.”

“That must have been when Karl shoved the mattress against the sea chest.”

“Exactly, but we still had to fasten the plug into place. Finally, Alfonso whaled at it with a sledgehammer and whacked that plug into the hole, which stopped most of the water. Alfonso ordered the bilges to keep pumping full tilt and full time, until we get to dry dock. What a night!”

“Were you scared?” I asked.

“I didn’t get scared until afterward. Thank God the plug worked.”

Then he gave a shy grin.“The ship’s carpenter and I celebrated with a bottle of rum at the bow as we watched the sunrise. I’m a bit looped. I’m off to sleep.”

✮

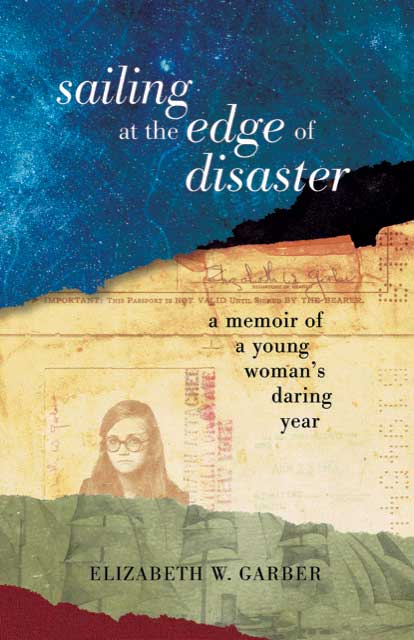

Elizabeth W. Garber is the author of Implosion: A Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter, Maine (Island Time), and three books of poetry. Her poems have been read on NPR’s “The Writer’s Almanack.” She lives in midcoast Maine.

Sailing at the Edge of Disaster: A Memoir of a Young Woman’s Daring Year

by Elizabeth W. Garber, Toad Hall Editions, September 2022, $24.95

The book is available at indie bookstores or directly from the publisher.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.