Tidal Power Returns to Maine Waters

Photo courtesy ORPCA demonstration test turbine was installed in Cobscook Bay in 2010 and replaced by another in 2012 before being removed in 2014.

For the first time in a decade, the powerful tides of Cobscook Bay are generating electrical power through a turbine that is anchored to the ocean floor near Eastport. The turbine, which was placed in the bay in May, represents the latest step in the continuing effort to bring the energy of the rising and falling tides to the region’s electrical grid to provide electricity to Eastport.

Photo courtesy ORPCA demonstration test turbine was installed in Cobscook Bay in 2010 and replaced by another in 2012 before being removed in 2014.

For the first time in a decade, the powerful tides of Cobscook Bay are generating electrical power through a turbine that is anchored to the ocean floor near Eastport. The turbine, which was placed in the bay in May, represents the latest step in the continuing effort to bring the energy of the rising and falling tides to the region’s electrical grid to provide electricity to Eastport.

Turning powerful ocean tides into usable electricity has been touted for years as a potential predictable and renewable resource—not just for eastern Maine, but also for other places nationally that have sufficient tides. By the end of 2025, Ocean Renewable Power Co., which is based in Portland, Maine, hopes to deploy multiple turbines in the waters of Western Passage, an inlet of the Bay of Fundy that separates Maine from Canada, and connect them to the power grid feeding Eastport.

When that happens, it will be the first commercial tidal power generation site in Maine and the United States. ORPC is also working with partners in Alaska to identify potential sites in the Cook Inlet where it can install turbines to turn the power from the tides into electricity for a commercial market there.

While still years away, those efforts are part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s overall aim to have the nation’s first larger-scale commercial tidal power arrays up and running by 2030. Tidal power has the potential to generate up to 220 terrawatt hours—220 trillion watts—of electricity a year in the United States, enough to power up to 21 million homes, and Maine is one of the hotspots of development.

Between deploying new test turbines in eastern Maine and plans to do so in Alaska in the coming year, 2023 should prove to be a milestone in ORPC’s aim to produce tidal power for a commercial market, said Nathan Johnson, vice president of development at ORPC.

“This will be a huge year for us,” he said in an interview at the company’s waterfront offices in Portland.

ORPC deployed a small river turbine in the Millinocket Stream in Millinocket earlier this year. The demonstration system is being tested in partnership with the nonprofit organization Our Katahdin at the site of the former Great Northern paper mill. Images courtesy ORPC

ORPC deployed a small river turbine in the Millinocket Stream in Millinocket earlier this year. The demonstration system is being tested in partnership with the nonprofit organization Our Katahdin at the site of the former Great Northern paper mill. Images courtesy ORPC

What’s happening in Maine is part of the larger picture to develop marine power resources nationally. The Department of Energy’s Water Power Technologies Office says its ultimate goal is to commercialize marine power technologies and start a whole new industry.

Numerous organizations and universities are working on various aspects of marine power, and ORPC is at the forefront of developing tidal and river power, said Elaine Buck, the technology manager in the Water Power Technologies Office. When the time comes, different areas of the country will use different technologies to generate electricity from the natural flows of oceans and rivers depending on which resources—ocean tides, waves, river currents and the like—give them the best opportunities, Buck said.

“In the U.S., the development of tidal power is much further advanced than wave,” she said in an interview from her office in Washington, D.C. “We should be putting in the first commercial tidal arrays by 2030, and wave [power] is probably another five years after that.”

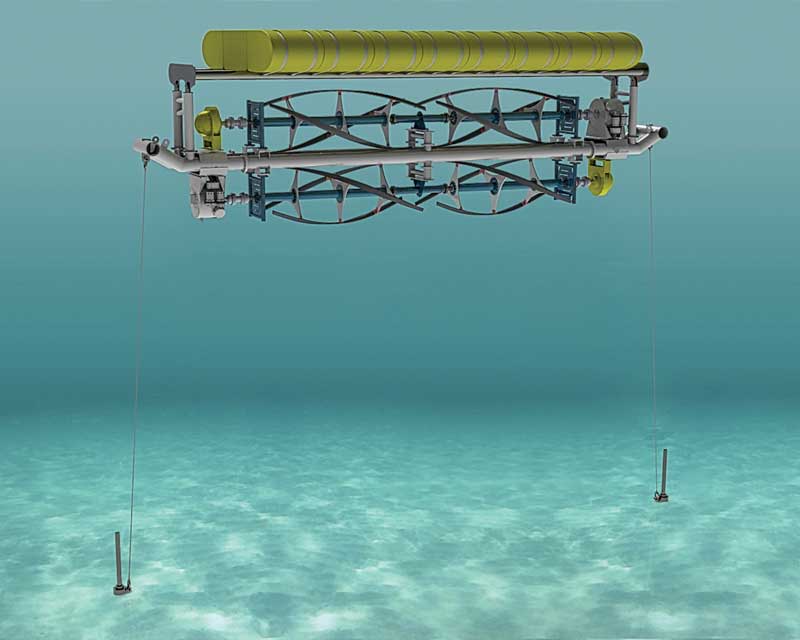

This illustration shows how the single tidal turbine installed in Cobscook Bay in May will be attached to the bottom. It will lead to a four-turbine system that will run for 12 months before multiple turbines are deployed in the Western Passage to generate power for Eastport. Image courtesy ORPC

This illustration shows how the single tidal turbine installed in Cobscook Bay in May will be attached to the bottom. It will lead to a four-turbine system that will run for 12 months before multiple turbines are deployed in the Western Passage to generate power for Eastport. Image courtesy ORPC

ORPC made quite a splash when it lowered its first demonstration tidal turbine into the waters of Cobscook Bay in 2010. With dignitaries watching, the 50-foot turbine—with teardrop-shaped blades that looked kind of like a rotary push mower—represented the first stage of tidal power development in Maine. At the time, the company’s CEO, referring to the site of the Wright Brothers’ flight, declared Eastport as “the Kitty Hawk of tidal energy.”

That first turbine was later replaced by another turbine that connected to the grid and could provide backup power for up to 25 homes as part of a pilot project. But due to complications, it was short-lived and was removed in 2014.

Now the company is giving downeast tidal power another shot. This spring it installed a new redesigned turbine as a demonstration project. The reconfigured blades, or foils, are more efficient and a buoyancy device helps keep it floating off the ocean bottom, while still anchored to a steel framework that was installed more than a decade ago for the original turbine.

“A single turbine test will lead to a four-turbine test,” Johnson explained. “That four-turbine system will run for 12 months, and the lessons learned that we take away from that project will lead to transitioning that technology to Western Passage.”

Whatever happens, tidal power development in Maine is just a sliver of the potential nationally. According to a 2021 report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the total marine energy technical resource in the 50 states is 2,300 TWh per year—equivalent to 57 percent of the electricity generated in the country in 2019. “Marine power” is defined as being in five areas: tidal currents, waves, ocean currents, river currents, and what is known as ocean thermal gradients.

The report does not forecast how much of that power actually will be captured, but notes that if even a small portion of the resource is harnessed, then marine power would make significant contributions to the nation’s energy needs. If just 10 percent of the available marine energy resources is utilized, it would equate to nearly 6 percent of the nation’s current electricity generation—or enough to power 22 million homes.

The U.S., of course, isn’t the only place where tidal power is in development. The United Kingdom and Europe are farther advanced than here, and progress is moving forward in Canada. In the Canadian waters of the Bay of Fundy, for instance, Canadian companies are testing floating turbines on the ocean surface aimed at producing electricity. The Bay of Fundy is home to the world’s largest tidal variations, with tides of up to 50 feet in the upper bay between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Marty Grohman, the president of E2Tech, said tidal energy could play a supporting role in Maine’s energy mix in select places. E2Tech, based in Biddeford, is a member-based organization comprised of individuals, businesses, and organizations involved in Maine’s environmental and energy technology economy.

“The predictability of tidal will always be a significant advantage,” he said. “I can tell you a year from today what the tide is going to do. There’s no other renewable resource that I know of that can do that.”

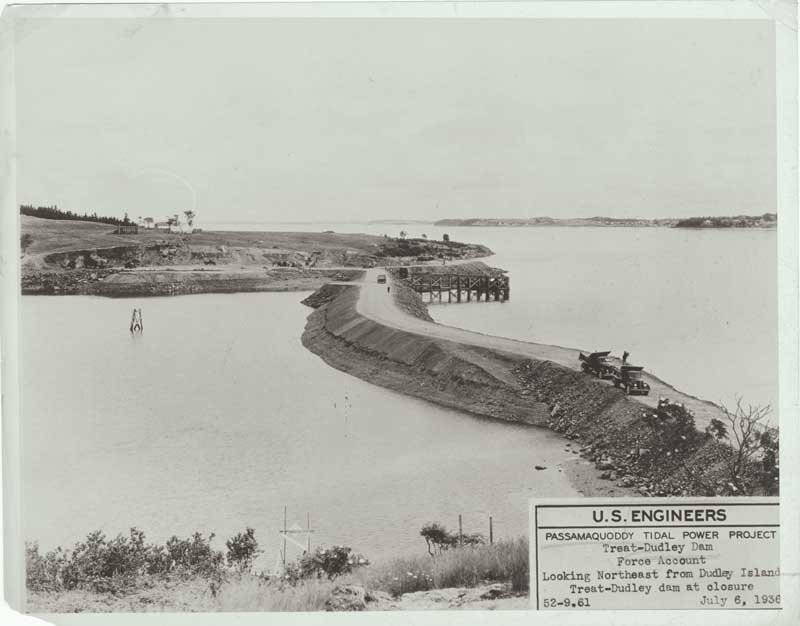

Harnessing the tide for energy goes back a long way in Maine, starting with tidal mills in the 1700s. In the 1930, President Franklin Roosevelt, who summered on nearby Campobello Island, promoted a massive tidal power project downeast. This image from the collection of the Tides Institute in Eastport shows a dam under construction in 1936. Image courtesy Tides Institute

Harnessing the tide for energy goes back a long way in Maine, starting with tidal mills in the 1700s. In the 1930, President Franklin Roosevelt, who summered on nearby Campobello Island, promoted a massive tidal power project downeast. This image from the collection of the Tides Institute in Eastport shows a dam under construction in 1936. Image courtesy Tides Institute

Besides tidal power, ORPC has also developed devices that capture energy produced from river currents. It now has a floating river turbine, called RivGen system, on a river that produces power for the village of Igiugig, Alaska, and plans to deploy a second turbine there by the end of this summer. It has another turbine in the Canadian village of Seven Sisters Falls, Manitoba. These turbines are designed to produce power for those isolated communities, either replacing or backing up diesel-powered generators. In Maine, ORPC this year also deployed a smaller demonstration RivGen system for trials at a test site in the Millinocket Stream in Millinocket.

The smaller modular river turbines are designed for places like canals, streams, and water channels below dams to produce power for localized sites that need electricity, whether they be electric vehicle-charging stations or isolated emergency services facilities.

The company is also looking at other communities in southern Chile where the systems could be deployed to replace diesel generators.

Taken as a whole, the move forward for tidal power and river power is critical toward the long-term strategy to turn potential into reality, Johnson said.

“This year, and the years to follow, are critical to us as a company,” he said, “but also to the industry as a whole.”

✮

Clarke Canfield is a longtime journalist and author who has written and edited for newspapers, magazines, and The Associated Press. He lives in South Portland with his wife.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.