Characters of the Allagash

All images from the Tim Caverly Collection

Umsaskis Lake is one of the large bodies of water in the Allagash Wilderness. Photo by Steve Day

Umsaskis Lake is one of the large bodies of water in the Allagash Wilderness. Photo by Steve Day

Scan the upper left-hand corner of any Maine map and you will see a thin blue line running from south to north. This line is the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, a 92-mile canoe route along a river created thousands of years ago, when melting water from retreating glaciers flowed north. Eleven thousand years ago, native Americans arrived on the scene, and relics from their existence can still be found today.

It’s an area that I know well from my time as a Maine ranger and Waterway supervisor, where you never knew what—or who—you might run into, while making the rounds. Here’s a tale about one interesting day on the job.

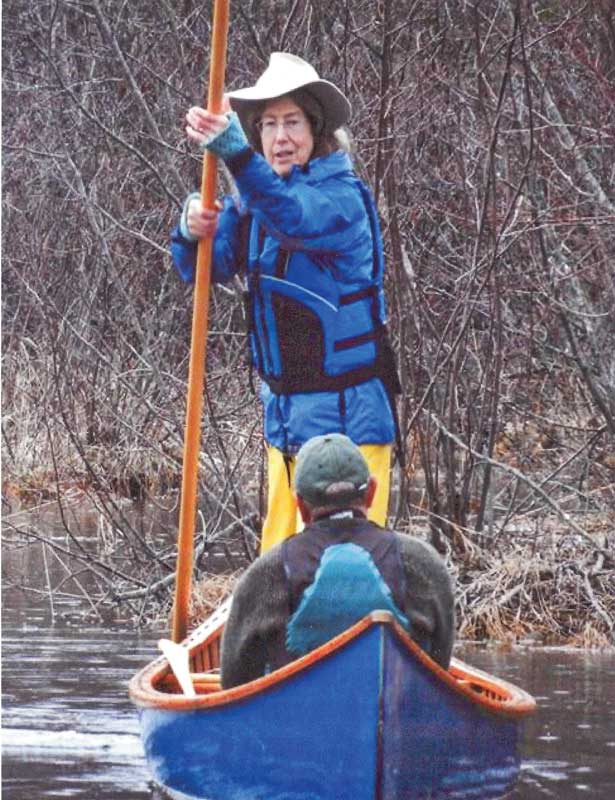

Master Maine Guide Alexandra Conover Bennett poles a canoe along the Allagash, just as wilderness guides have been doing for ages.

By the 1900s, game wardens were hired by the state to protect Maine’s fish and wildlife. One such man was Henry Taylor. In the 1940s he, with his wife, Alice, built a set of sporting camps on the east side of the river, two miles south of the 44-foot high Allagash Falls. The couple summered there until 1984.

Master Maine Guide Alexandra Conover Bennett poles a canoe along the Allagash, just as wilderness guides have been doing for ages.

By the 1900s, game wardens were hired by the state to protect Maine’s fish and wildlife. One such man was Henry Taylor. In the 1940s he, with his wife, Alice, built a set of sporting camps on the east side of the river, two miles south of the 44-foot high Allagash Falls. The couple summered there until 1984.

As supervisor, it was my responsibility to check on the Taylors from time to time, so one summer morning, Ranger Lee Hafford and I motored our canoe 40 minutes north from the Michaud Farm ranger station to the Taylors’ camps. When we arrived, a man was standing on the porch and he waved us in for coffee.

Even in his 80s, Henry, standing tall, gave the bearing of being at home in the wilderness. He was dressed in summer attire of green cotton pants held up by red suspenders and a wide leather belt. The sleeves of his red-and-white checked shirt were rolled up to expose slightly yellowed long johns. On his feet, Henry wore light homemade knit stockings and camp moccasins.

Residing in a three-room, hand-hewn log home, the couple was happy to have visitors. Alice quickly handed us two steaming mugs of boiled lumberjack coffee and we were invited to sit at the table. The coffee was so strong, it would have melted a spoon.

While we sipped the bitter liquid, Henry said, “Excuse me, I gotta take my medicine.” Walking toward the sink, he reached up into a cupboard, and grabbed a pint-sized canning jar from a top shelf. It was full of dried furry brown objects measuring about 2 inches long by 3/4 of an inch wide. Henry removed one, placed it in an empty juice glass which he topped off with vodka and placed the concoction on the sideboard to soak.

After a bit, the old trapper grabbed the glass and quickly gulped the liquid. He made a loud smacking noise and wiped his lips with the back of his hand.

Henry noticed that I was watching, so with a toothless grin, he asked, ‘“Have you ever had a snifter of beaver castor?”

Smiling, I replied, “I don’t think so. I don’t even know what a castor is.”

Like a professor teaching an outdoor class, the old woodsman told me about beaver organs. He explained, “Castors are the scent gland of a beaver. Both male and female have two such body parts; one on each side of the creature’s hind end. In proper markets the secretors can bring $50 a pound.”

Patiently, the old man continued, “Many outdoorsmen use the castor as a trapping lure. However, the gland has other uses, such as making women’s perfume and as a flavor additive for food. What isn’t realized is that the organ also has medicinal properties. When dropped into a liquid and allowed to soak, the mixture is a remedy that calms the heart.

“Now mind you, don’t eat the castor because it tastes terrible,” he advised. “While normally they are soaked in hot tea, I prefer mine in a glass of vodka. I’ve had one every morning for most of my 80-plus years, and because of that and my ‘ti-blanc’ (Henry’s slang for vodka), I can still do things that men half my age can’t.”

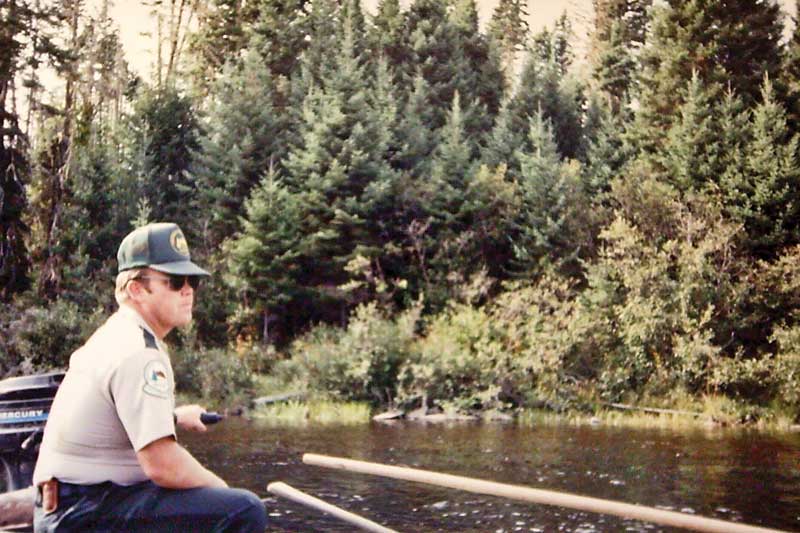

Allagash Wilderness Waterway Supervisor Tim Caverly is on patrol.

Allagash Wilderness Waterway Supervisor Tim Caverly is on patrol.

Smiling at the old-fashioned recipe, I inquired, “Henry, I’m curious about something, can I ask you a question?” Taking one last look through the kitchen window at the river, Henry nodded and walked across the paint-worn floorboards to sit at the head of the table.

“I understand that some time ago, the State tried to stock landlocked salmon in the Allagash; do you know about the experiment?” Waiting, I carefully sipped my coffee so that the scalding liquid wouldn’t burn my lips.

Alice answered for Henry saying, “Yes, he does.” Then the woman nodded at her husband and said, “Now you tell the story the right way Henry, and don’t make anything up either.”

Without a word Henry accepted the instructions, tipped his chair back onto its two hind legs, and with his feet braced flat on the floor; he placed huge hands on the worn spots above the knees of his pants and began his tale.

“Years ago, before roads, the State Fish and Game said they wanted to stock salmon in Priestly Lake, west of Umsaskis Lake,” he said. “In 1924, I was hired to be a game warden. Shortly afterward, I was ordered to take my canoe downriver to Fort Kent and pick up smolt. There, I was given 5,000 little salmon and told to transport them by canoe 40 miles up the St. John River. After reaching my camp, I continued using my 12-foot spruce canoe pole to move the live fish, 30 miles up the Allagash.

“After reaching Umsaskis, I carried the salmon 3 miles over land to Priestly Lake, where the smolt were released. That was the State’s stocking program in the ’20s and ’30s.”

It was a story that I was glad to hear told first hand. While Henry talked, Alice busily cooked doughnuts in a cast iron frying pan. She listened closely while moving briskly about the small kitchen to make sure Henry didn’t stray too far afield.

As Lee refilled our cups from the nearby stove, Henry said, “I am feeling a little poorly today, I do believe I need some more remedy!” With that he poured a second glass of the clear liquid, added a new castor, and downed the liquor in one gulp.

Once seated, we talked a bit more about early life on the river, and Henry told the salmon-stocking story again and stated, “I do believe a weather front is heading this way. I think I need more medicine.” Henry coughed and poured a third glass.

Afterward he said, ‘“I feel better now. Have I told you about how the State wanted to put salmon in the Allagash?” Without waiting for an answer, he proceeded to tell us the story a third time, though this time we learned that single-handedly he had carried 50,000 salmon in a bucket over 80 miles in a canoe.

We thanked the Taylors for the coffee, accepted the offer of a fresh doughnut, and walked out the door with the aroma of the frying treat trailing behind.

Nearing the river, we waved goodbye and turned to step into our aluminum craft. Once we were seated, we saw two men paddling on the same side of a heavily loaded canoe. Recognizing the visitors as beginners, Lee observed, “Propelling that way, those fellows are apt to swamp anytime.”

When they asked us how far to the turnout at the head of the Falls I started to reply, “Almost 3 miles,” but before I could finish, both waved their plastic oars in the air and hollered, “Let’s do this!” Driving the silver blades into the river, the two sped off mid-sentence as I tried to finish, “Look for the Portage Trail sign on the right at the head of the 40-foot-high drop. Don’t go over the..!” I warned as they floated out of ear shot.

Once we were back in our patrol boat, a family of campers across the river waved us to shore. Lee shut off the outboard as a woman and child came to greet us. After we answered their questions about historic Allagash log drives, Lee and I once again headed north. Shortly we arrived at the falls landing only to find a hectic scene.

People were pointing downstream and hollering, “Ranger, ranger, two men just went over the falls. Can you help them?”

A photographer managed to capture two men and their canoe going over the 40-foot Allagash Falls.

A photographer managed to capture two men and their canoe going over the 40-foot Allagash Falls.

Grabbing a rescue rope, we ran down the trail, only to find the two men we’d seen earlier standing by a battered canoe; both were soaking wet and bruised.

Campers had provided dry towels while others had taken canoes to the foot of the torrent to recover a cooler, assorted gear, and a wanigan box.

Nearing the men, I asked,” Are you okay? Did you go over the falls?”

Embarrassed, the older one explained, “Yes. We were moving so fast, we paddled right into the turbulence. Then the bow went under water, hit a piece of ledge, which catapulted us out of the canoe, into the deep pool below. We’re a little sore, but I don’t think we broke anything except our canoe,” he said as he pointed to a huge hole.

Realizing their loss of transportation, the same man stated, “We must leave today. Is there a way to get another canoe? Our truck is in Allagash Village.”

Before Lee and I could answer, one of campers offered, “We have a group of eight, with four canoes. Our party leaves tomorrow, we can double up so you can use one of ours. Just leave it at Norm

L’Italien’s parking lot.”

“That’s mighty gracious of you,” the younger man replied. “We’d be happy to pay you.”

Turning down the offer of money, the folks helped the inexperienced victims on their way. Back on the water, the two moaned and groaned with every stroke while heading downriver.

For us, it was just another work day with the characters on the Allagash.

✮

Tim Caverly is a Maine native, author, and lecturer, and was supervisor of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway for 18 years. He and his wife, Susan, have published 12 books and he pens a monthly column in The Maine Sportsman newspaper.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.