- Aquaculture in Maine

- Farmed Mussels Thrive as Wild Population Declines

Farmed Mussels Thrive as Wild Population Declines

Farmed mussels are actually in greater demand than wild; they are larger, plumper, and more meaty, connoisseurs say.

This article is part of a series in our Special Report on Aquaculture in Maine. Continue reading the rest of this series at the end of this article.

Rudy Gutierrez-Lino harvests mussels grown by Hollander + DeKoning off the north shore of Mt. Desert Island. Photo courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Rudy Gutierrez-Lino harvests mussels grown by Hollander + DeKoning off the north shore of Mt. Desert Island. Photo courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Mytilus edulis, the common blue mussel, grows wild throughout the North Atlantic and was once prolific in Maine’s intertidal zones where thrifty Mainers harvested them by the bucketful (except for those who scorned them as poverty food). In recent years invasive green crabs and native eider ducks have decimated the wild intertidal population, but plump and succulent Maine mussels are still available because of shellfish farmers like Josh and Shey Conover at Marshall Cove and Flat Island off Islesboro.

The couple, who also run a boatyard on Islesboro—where Josh is an active lobsterman with a string of 800 traps—are relative newcomers to mussel farming, although Josh worked briefly with Great Eastern, a pioneering Maine mussel farm that ceased operations around 2008. Shey had worked at the Island Institute in Rockland so it was natural for them to turn to the Institute’s Aquaculture Business Development Program for help connecting their start-up with others in the industry.

Josh says he’s not a native islander. “I moved out there when I was 10 and I started right out lobster fishing with a friend, from a canoe,” he recalled.

Why mussel farming? There is a lot of competition in oyster farming, not so much in mussels. “Besides, he was seeing changes in lobstering,” Shey interjected, “recognizing that both his body and the fishery may not last forever, but he’s always looking for things to do that will let him stay on the water.” Her own moment of light came after a talk by Maine Aquaculture Association’s director, Sebastian Belle, about economic diversification. “We should start a mussel farm!” she said, thinking it would give them a good winter activity to complement the boatyard and lobstering. “We were a little naïve,” she admitted. “Somehow it didn’t register that no matter what you’re doing in Maine, everything happens in June.”

“The seasonality of it hasn’t been seamless,” Josh added. “We actually harvest year-round.”

Josh Conover with a thick line of rope-grown mussels at his Marshall Cove farm off the northwest tip of Islesboro. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

Josh Conover with a thick line of rope-grown mussels at his Marshall Cove farm off the northwest tip of Islesboro. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

The Conovers’ mussel operations are based on large sturdy rafts anchored to the bottom; the mussels grow on hefty ropes suspended from the rafts. It’s not cheap to set up a mussel farm. Josh mentioned a figure of $6,000-$7,000—“but we already had the boats.” Still, once the rafts with their coiled ropes are in place, it’s just a question of waiting for mussel spawn floating past and attaching themselves, usually in the spring, which is around May in Islesboro waters. Toward the end of July, when the seed is set, the lines are uncoiled and let out. The mussels grow on the suspended lines until November, and then are stripped off and moved to a sock that gives then more space for growth. One raft of seeds, Shey said, should produce two rafts of product.

In March 2020, the Conovers harvested around 3,000 pounds a week, selling the mussels for $2 a pound. In 2019 they harvested 200,000 pounds in all. “We’d like to get up to 6,000 pounds a week,” Josh said, “but we’re still very much on a ramp-up stage with our market.”

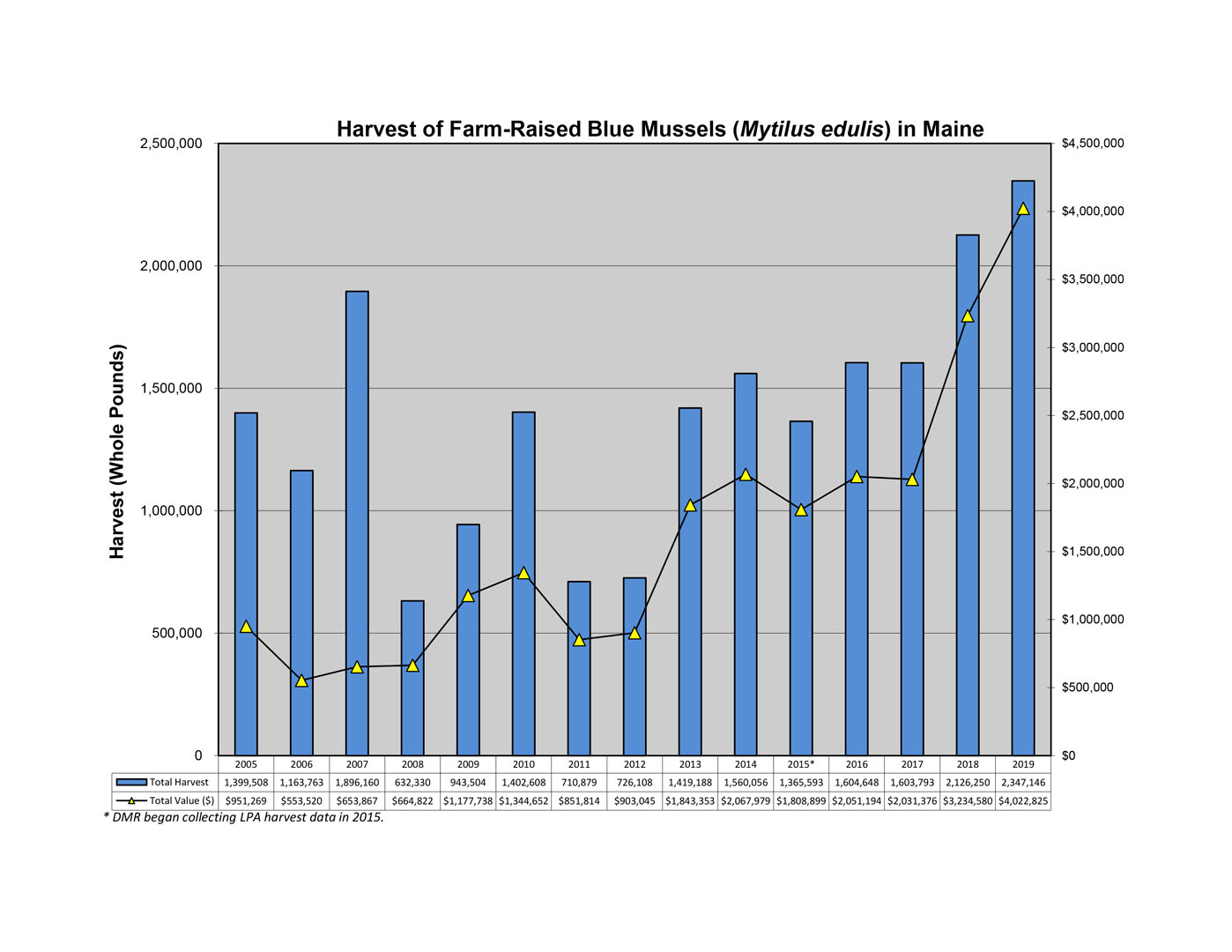

A chart from Maine’s Department of Marine Resources shows the growth in the state’s harvest of farm-raised mussels over the past few years.

Mussel farming has had its ups and downs in Maine over the years, beginning back in 1975 when the quasi-legendary Ed Myers applied for Maine Aquaculture License No. 1 to cultivate mussels in Clarks Cove, next to the Darling Center. Since then mussel farms have come and gone but the practice is now well-established with seven farms currently operating. The largest is Bangs Island Mussel Farms in Casco Bay where Gary and Matt Moretti, a father-son team, raise mussels along with sugar kelp. Farmed mussels are actually in greater demand than wild; they are larger, plumper, more meaty, connoisseurs say.

A chart from Maine’s Department of Marine Resources shows the growth in the state’s harvest of farm-raised mussels over the past few years.

Mussel farming has had its ups and downs in Maine over the years, beginning back in 1975 when the quasi-legendary Ed Myers applied for Maine Aquaculture License No. 1 to cultivate mussels in Clarks Cove, next to the Darling Center. Since then mussel farms have come and gone but the practice is now well-established with seven farms currently operating. The largest is Bangs Island Mussel Farms in Casco Bay where Gary and Matt Moretti, a father-son team, raise mussels along with sugar kelp. Farmed mussels are actually in greater demand than wild; they are larger, plumper, more meaty, connoisseurs say.

Tiny seed mussels, captured from the wild, cling to coils of rope at Marshall Cove Farms. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Rope-grown mussels—stout ropes tightly clustered with blue-black mussels hanging from partially submerged rafts—is the method favored by most Maine mussel farmers. But an unusual technique, at least for Maine, was brought here by Theo DeKoning, a fifth-generation mussel farmer from the Netherlands who came to Maine in 2004, fell in love (who doesn’t?) and brought his family and business to settle here in 2005.

Tiny seed mussels, captured from the wild, cling to coils of rope at Marshall Cove Farms. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Rope-grown mussels—stout ropes tightly clustered with blue-black mussels hanging from partially submerged rafts—is the method favored by most Maine mussel farmers. But an unusual technique, at least for Maine, was brought here by Theo DeKoning, a fifth-generation mussel farmer from the Netherlands who came to Maine in 2004, fell in love (who doesn’t?) and brought his family and business to settle here in 2005.

Theo DeKoning, here with his two sons and business partners, Max and Alex, settled in Maine in 2005, bringing the Dutch process of mussel culture that his family had practiced in Holland for many generations. Photo courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Acadia Aqua Farms, operated by Theo, his wife Fiona, and their sons Max and Alex, has leases in the Mt. Desert Narrows, between the big island and the mainland. The technique they employ, capturing wild mussel seed under license, then depositing the seed on the sea floor in protected areas, is typical of Dutch mussel farms and has a centuries-long history in the Low Countries. It has adapted well to the coast of Maine where the environment creates the robust flavors and substantial meats for which Hollander + DeKoning mussels are renowned. “They taste like Maine,” Fiona DeKoning said with evident pride. As newcomers to the state, indeed as foreigners, the DeKonings try hard, they said, to be respectful of their neighbors and their neighbors’ ideas, as well as to be responsible citizens—Fiona sits on the Maine Aquaculture Associations board of directors where she is vice president.

Theo DeKoning, here with his two sons and business partners, Max and Alex, settled in Maine in 2005, bringing the Dutch process of mussel culture that his family had practiced in Holland for many generations. Photo courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Acadia Aqua Farms, operated by Theo, his wife Fiona, and their sons Max and Alex, has leases in the Mt. Desert Narrows, between the big island and the mainland. The technique they employ, capturing wild mussel seed under license, then depositing the seed on the sea floor in protected areas, is typical of Dutch mussel farms and has a centuries-long history in the Low Countries. It has adapted well to the coast of Maine where the environment creates the robust flavors and substantial meats for which Hollander + DeKoning mussels are renowned. “They taste like Maine,” Fiona DeKoning said with evident pride. As newcomers to the state, indeed as foreigners, the DeKonings try hard, they said, to be respectful of their neighbors and their neighbors’ ideas, as well as to be responsible citizens—Fiona sits on the Maine Aquaculture Associations board of directors where she is vice president.

Hollander + DeKoning mussels, cleaned, bagged and ready to move to market. Photo Courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Hollander + DeKoning mussels, cleaned, bagged and ready to move to market. Photo Courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Maine-grown mussels have a disadvantage in that they cost more than their equivalents from Prince Edward Island, where mussels are produced in almost industrial quantities. The test, however, is in the eating and most high-end chefs and restaurants agree that, grown slowly in our cold, salt-smacked waters, Maine mussels, with their intense flavor and meaty texture, are well worth the price.

Stewardship is Hollander + DeKoning’s scow-like barge, used for on-the- water activities like harvesting wild mussels under license from the State of Maine. Photo Courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Stewardship is Hollander + DeKoning’s scow-like barge, used for on-the- water activities like harvesting wild mussels under license from the State of Maine. Photo Courtesy Hollander + DeKoning

Special Report: Aquaculture in Maine

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.