This article is part of a series in our Special Report on Aquaculture in Maine. Continue reading the rest of this series at the end of this article.

Keith Miller and crew harvest a kelp line in Spruce Head. Planted in fall and harvested in spring, kelp is an ideal crop for lobster fishermen after hauling their traps for the winter. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

Keith Miller and crew harvest a kelp line in Spruce Head. Planted in fall and harvested in spring, kelp is an ideal crop for lobster fishermen after hauling their traps for the winter. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

Sea vegetables is the polite term, but seaweed is what we call it in Maine, and it covers an enormous range of submerged plant life, or macroalgae, including Irish moss or carageenan, rockweed and bladderwrack, laver, dulse, kelp, and half a dozen other species.

Many of these are harvested in the wild, especially Irish moss and rockweed, although there is also a steady market for wild kelp and dulse (Palmaria palmata). But increasingly Maine fishermen and water farmers are focusing on the possibilities offered by aquaculture, growing seaweed and especially the kelps—sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima), winged kelp (Alaria esculenta), and horsetail kelp (Laminaria digitata). Seaweeds in general have a multitude of medicinal and cosmetic uses, but the culinary possibilities offered by kelp make it more interesting, especially for lobster fishermen looking to augment their incomes with an alternative product.

Atlantic Sea Farm partners with fishermen along the coast to grow kelp. Here, Justin Papkee from Long Island and his crew harvest skinny kelp from lines off Chebeague Island. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean ClusterSeaweed fits that bill very neatly. Planted in October after many fishermen have hauled their traps, the kelp grows quietly throughout the winter months in long lines that stretch below the water surface, protected from ice and turbulence. By May, just when it’s time to start thinking about getting lobster traps ready to set out again, the big sheets, now as much as 14 feet long, are ready to harvest.

Atlantic Sea Farm partners with fishermen along the coast to grow kelp. Here, Justin Papkee from Long Island and his crew harvest skinny kelp from lines off Chebeague Island. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean ClusterSeaweed fits that bill very neatly. Planted in October after many fishermen have hauled their traps, the kelp grows quietly throughout the winter months in long lines that stretch below the water surface, protected from ice and turbulence. By May, just when it’s time to start thinking about getting lobster traps ready to set out again, the big sheets, now as much as 14 feet long, are ready to harvest.

And then? Where, I asked seaweed farmers, is the market for all that seaweed? Macrobiotics? Asian restaurants? Health food stores?

Atlantic Sea Farms hopes to have the answer(s). The company began life more than 10 years ago as a seaweed farm called Ocean Approved. Since then, under the direction of CEO Briann Warner, the company has reshaped itself, sold off its seaweed farms, and morphed into a marketing and distributing outfit for 20 or so independent Maine seaweed farmers—folks like Karen Cooper on North Haven, Elijah Brice in Eastport, or Ben Stendel and Keith Miller in Spruce Head. “Since 98 percent of all the seaweed consumed in America is imported, and often from very questionable sources, there’s a great market for our guaranteed sustainable, home-grown products,” Warner said.

The grocery shelf for Maine seaweed has actually grown significantly in recent years as consumers discover its virtues. Once relegated to Asian recipes, seaweed, whether dried or fresh, is finding a place throughout the cook’s repertoire. Seaweed, in fact, is a nutritional bomb, rich in vitamins (A, C, D, E, and B) and minerals (calcium, magnesium, potassium, and others) and it’s a surprisingly good source of Omega-3 fatty acids despite being low in fat.

Atlantic Sea Farms produces a variety of products from fresh Maine seaweed, including seaweed salad, Sea-beet Kraut, and Sea-Chi, a kind of seaweed kimchi. Products like this have fueled a growing interest in seaweed. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean ClusterAtlantic Sea Farms produces only from fresh, never dried, seaweed. Kelp is cooked, then frozen and preserved in value-added products like lightly fermented seaweed salad, or a tasty sauerkraut mix of beets, kelp and ginger. It’s also sliced in thin “pasta” strips that can be served as a side vegetable, and it’s pureed and frozen in cubes to toss into a smoothie, a soup, or a pasta sauce, boosting both flavor and nutrition.

Atlantic Sea Farms produces a variety of products from fresh Maine seaweed, including seaweed salad, Sea-beet Kraut, and Sea-Chi, a kind of seaweed kimchi. Products like this have fueled a growing interest in seaweed. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean ClusterAtlantic Sea Farms produces only from fresh, never dried, seaweed. Kelp is cooked, then frozen and preserved in value-added products like lightly fermented seaweed salad, or a tasty sauerkraut mix of beets, kelp and ginger. It’s also sliced in thin “pasta” strips that can be served as a side vegetable, and it’s pureed and frozen in cubes to toss into a smoothie, a soup, or a pasta sauce, boosting both flavor and nutrition.

Seth Barker with some of the sugar kelp grown on the seaweed farm he manages with Peter Fischer at Clark’s Cove in Walpole. Photo by Nancy Harmon JenkinsAt Maine Sea Farms, partners Seth Barker and Peter Fischer take a relaxed approach, marketing fresh and dried seaweed to an impressive list of restaurant chefs. Down at Clarks Cove on the Damariscotta River where so much of Maine aquaculture gets its start, they grow kelp, skinny kelp, and alaria. Barker is a marine biologist, formerly with the state Department of Marine Resources, while Fischer is sales and marketing manager at Pemaquid Mussel Farms.

Seth Barker with some of the sugar kelp grown on the seaweed farm he manages with Peter Fischer at Clark’s Cove in Walpole. Photo by Nancy Harmon JenkinsAt Maine Sea Farms, partners Seth Barker and Peter Fischer take a relaxed approach, marketing fresh and dried seaweed to an impressive list of restaurant chefs. Down at Clarks Cove on the Damariscotta River where so much of Maine aquaculture gets its start, they grow kelp, skinny kelp, and alaria. Barker is a marine biologist, formerly with the state Department of Marine Resources, while Fischer is sales and marketing manager at Pemaquid Mussel Farms.

One chilly March afternoon they took me out to inspect a barely submerged line on which strands of sugar kelp were growing. Barker pulled the line out of the water to show me the fleshy, dark-golden, glistening wings of kelp as Fischer explained the process. Growing sea vegetables requires a minimum investment, he said. “You need a lease, of course, and you need to buy the line with the kelp spores embedded in it and some two-inch PVC pipe and that’s about it. And an old boat,” he added. The two men had seeded 4,000 feet of line the previous October and expected to harvest their main crop in May—“probably around 40,000 pounds of seaweed,” Barker said, “but that’s total biomass.”

Peter Fischer holds up a long tail of sugar kelp. He and his business partner, Seth Barker, market fresh and dried seaweed to restaurant chefs. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins“The market is just developing,” Fischer explained, “there’s lots of room for growth. What it represents for Maine is a highly sustainable expansion of the food base. We don’t need to irrigate, we don’t need to fertilize, we just let it grow.”

Peter Fischer holds up a long tail of sugar kelp. He and his business partner, Seth Barker, market fresh and dried seaweed to restaurant chefs. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins“The market is just developing,” Fischer explained, “there’s lots of room for growth. What it represents for Maine is a highly sustainable expansion of the food base. We don’t need to irrigate, we don’t need to fertilize, we just let it grow.”

Ocean’s Balance is another Maine seaweed processor, specializing in dried products such as dulse, a salty snack that has a considerable following with downeasters, kombu (Laminaria), which is used as the base for miso soup (also for a most-excellent chowder), and wakame (Undaria pinnatifida), which can be rehydrated to make seaweed salads or just added to boost umami flavors in many dishes. With the growth in popularity of Asian cuisines, especially Japanese, consumers have become accustomed to these products. Ocean’s Balance also makes a kelp puree sold in jars to spoon into a soup or stew, again adding that umami boost that good chefs and their customers seek.

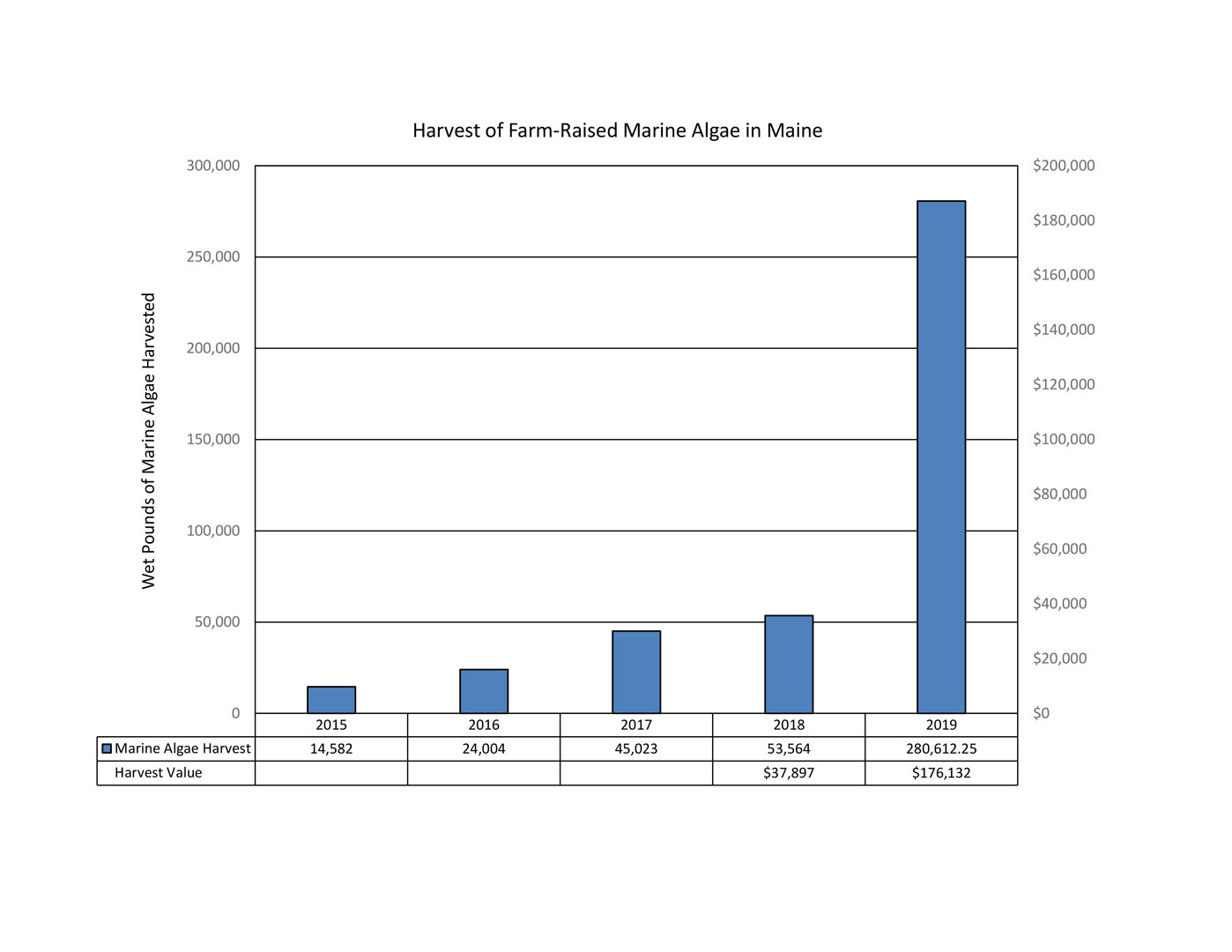

A chart created by Maine’s Department of Marine Resources shows how quickly the value of the state’s seaweed harvest has grown. At Atlantic Sea Farms, Warner (who had an unusual early career as a development economist with the U.S. Foreign Service, serving in hot spots like Libya and South Sudan) sees a bright future for seaweed farming in Maine. “It really plays a lot to fishermen’s strengths,” she said in a conversation in her Saco warehouse office. “Because it’s low-capital entry compared to other kinds of aquaculture, because it grows over a mud bottom so there’s no conflict, it’s grown in winter, counter-seasonal to lobstering, so there’s no problem with gear. And it’s pretty straightforward for fishermen—they have equipment, they have knowledge of the water, and they have social capital to make fantastic farmers. We work with people who already have these incredible assets.”

A chart created by Maine’s Department of Marine Resources shows how quickly the value of the state’s seaweed harvest has grown. At Atlantic Sea Farms, Warner (who had an unusual early career as a development economist with the U.S. Foreign Service, serving in hot spots like Libya and South Sudan) sees a bright future for seaweed farming in Maine. “It really plays a lot to fishermen’s strengths,” she said in a conversation in her Saco warehouse office. “Because it’s low-capital entry compared to other kinds of aquaculture, because it grows over a mud bottom so there’s no conflict, it’s grown in winter, counter-seasonal to lobstering, so there’s no problem with gear. And it’s pretty straightforward for fishermen—they have equipment, they have knowledge of the water, and they have social capital to make fantastic farmers. We work with people who already have these incredible assets.”

Atlantic supplies growers with free seed and helps set them up in business, then guarantees to buy the entire crop. Processing into value-added products, she said, is more capital intensive: “But if you make something that’s accessible, that’s delicious, that’s easy to eat—well, there’s no problem selling it if you can get the word out.” As part of getting the word out, in San Francisco in early 2020, Atlantic Sea Farms won a coveted Good Food Award, given to food crafters who “top the charts in a blind tasting and meet [our] environmental and social responsibility standards.” It was a well-deserved recognition for Maine seaweed producers.

Skinny kelp like this, has a salty savory flavor and a crisp texture that make it highly sought after by chefs. In addition to being good to eat and full of nutrients, the kelp helps improve water quality. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean Cluster

Skinny kelp like this, has a salty savory flavor and a crisp texture that make it highly sought after by chefs. In addition to being good to eat and full of nutrients, the kelp helps improve water quality. Photo courtesy Atlantic Sea Farms and the New England Ocean Cluster