- Aquaculture in Maine

- Maine-Grown Oysters Have a Well-Earned Reputation for Quality

Maine-Grown Oysters Have a Well-Earned Reputation for Quality

There are huge opportunities here for Maine to be a leader, not just in policy but in technical innovation as well.

This article is part of a series in our Special Report on Aquaculture in Maine. Continue reading the rest of this series at the end of this article.

Lane Hubacz of Basket Island Oyster Company hauls a cage of oysters up from the floor of Casco Bay. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

Lane Hubacz of Basket Island Oyster Company hauls a cage of oysters up from the floor of Casco Bay. Photo by Jack Sullivan, Island Institute

If Maine aquaculture has a show-stopper, a celebrity, a star performer, it is no doubt the oyster. Pale craggy bivalves from Maine, oyster-lovers contend, are pleasingly plump, with tastier, more satisfying meats than oysters from almost anywhere else—they have that balance of sweet and briny flavors that aficionados cherish. In the restaurants and oyster bars that have proliferated along the Maine coast—at the same rate, it seems, as the oyster farms themselves—as well as in distant big-city venues, Maine oysters are in demand.

A crisp, clean environment, long inlets where river and ocean waters join to make the right briny milieu, and tides that surge and drain, bringing fresh, frigid, salt water in and out regularly and without fail—that’s what makes Maine oysters all the rage. If you don’t believe me, listen to the Oysterater (yes, that is a real person, or persons. They rate the world’s oysters at www.oysterater.com): Maine oysters, when grown right, have “unparalleled depth, firmness, and complexity.”

Although a few farmers produce the flat European Belons, Ostrea edulis, most oysters grown in Maine are eastern oysters, Crassostrea virginica, native to the east coast.

Emily Selinger holds a generous handful of the young oysters she raises in Freeport. Selinger came back to her native Maine to become an oyster farmer after many years as a professional sailor up and down the East Coast. Photo Courtesy Emily Selinger

Emily Selinger holds a generous handful of the young oysters she raises in Freeport. Selinger came back to her native Maine to become an oyster farmer after many years as a professional sailor up and down the East Coast. Photo Courtesy Emily Selinger

Why, if they’re all the same species, do Maine oysters exhibit such different characteristics among locations along the coast? What distinguishes the crisp salty flavors of Bath’s winter points, from the tart, almost citrusy, sweetness of Damariscotta River-grown Pemaquids, or the metallic bite of Taunton Bays from downeast Acadia? The ocean, the Gulf of Maine, is not uniform. Each area, each inlet, each island cove or bay, is different from the others. Each has its own ecology, its own unique temperature, saltiness, and impact from land-based rivers and streams, as well as its own underlying geology, all of which contribute to variations in flavor, texture, and size.

Other factors include the many different techniques for growing the oysters; at what age and size the spawn or spats are set out; whether they are bottom-cultured or grown in the more typical semi-submerged cages; how frequently cages are cleaned of biofouling; whether the oysters are tumbled to produce deeply cupped shells or left in a natural state; and how long they take to reach maturity (usually two to three years). Cows produce different-flavored milk based on pasture grasses or silage in their diets; oysters develop different flavors based on all these factors, as well as the plankton and micro-algae on which they feed. “It’s their individual mer-oir,” said Peter Piconi, who until recently ran the Aquaculture Business Development Program at Island Institute, adapting the wine-making term terroir to the sea.

Right on the dock in Damariscotta, Jeff (Smokey) McKeen tends several mini-silos of baby oysters to furnish Pemaquid Oyster Company, which he founded back in 1986. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Right on the dock in Damariscotta, Jeff (Smokey) McKeen tends several mini-silos of baby oysters to furnish Pemaquid Oyster Company, which he founded back in 1986. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

At latest count there were more than 100 oyster farms of varying sizes up and down the coast of Maine, from east of Mount Desert all the way south to the Piscataqua River on the New Hampshire border. But the Damariscotta River is the Holy Grail for oyster lovers. The river system is a big estuary running 12 miles up from the ocean. It is tidal all the way to Damariscotta, its waters constantly flowing up and down with the tides, creating an ideal habitat for these bivalves. One other reason for this development is the location of the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center on the river at Clarks Cove near Walpole. Today, of the nine oyster farms along the river, at least seven have strong connections to the center.

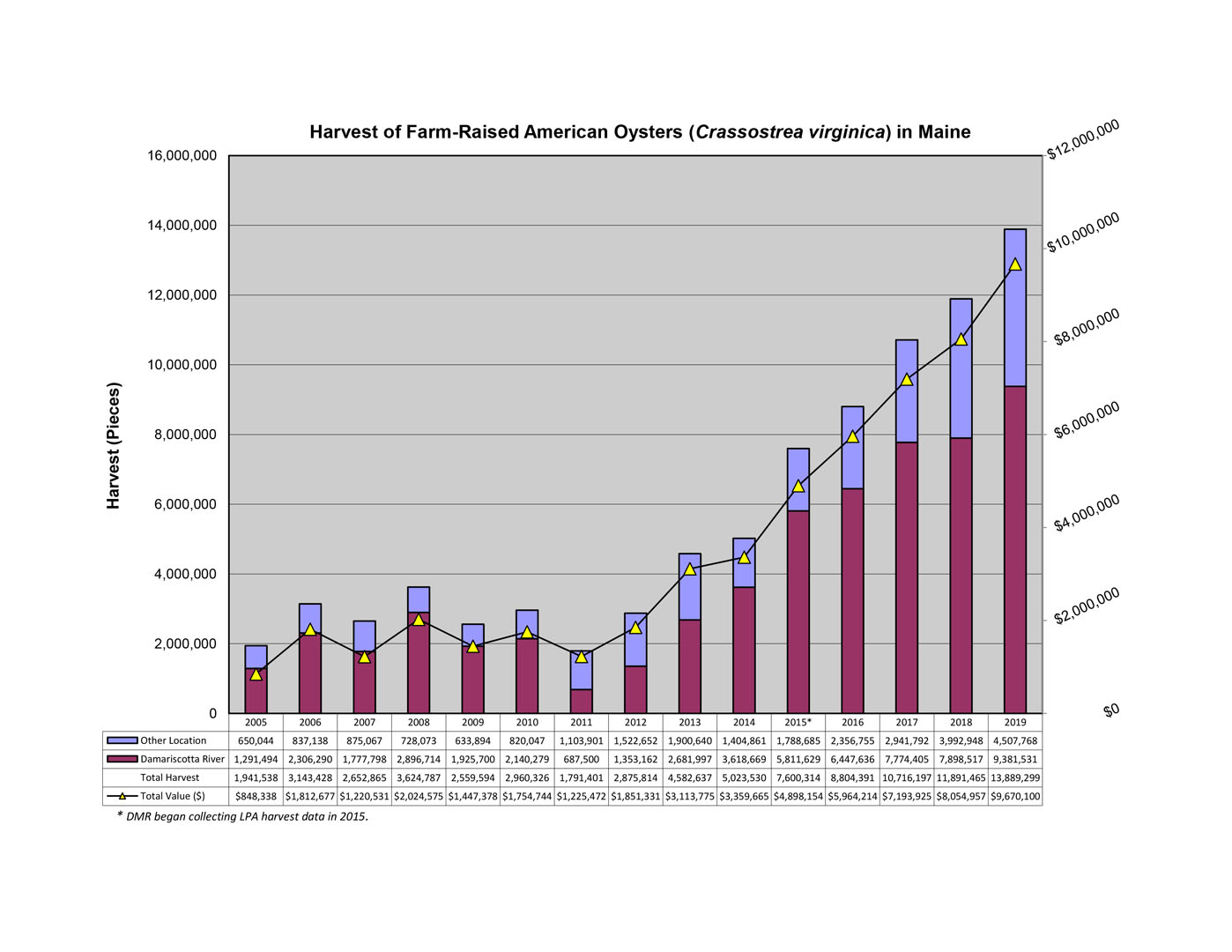

A chart from Maine’s Department of Marine Resources demonstrates the growth of Maine’s oyster harvest in recent years, jumping from 5 million oysters worth just under $3.4 million in 2014 to 13.9 million oysters worth $9.7 million in 2019.

A chart from Maine’s Department of Marine Resources demonstrates the growth of Maine’s oyster harvest in recent years, jumping from 5 million oysters worth just under $3.4 million in 2014 to 13.9 million oysters worth $9.7 million in 2019.

More than 80 percent of Maine’s most highly prized oysters come from the Damariscotta region. That’s not surprising, since this part of Maine has been home to superior shellfish for a couple of thousand years at least. The Whaleback Shellfish Middens (or what remains after late-19th century miners decimated them), on the banks of the river upstream from Damariscotta village, attest to the importance of shellfish in the diets of indigenous peoples.

At Mook Sea Farm, Bill Mook raises oyster seed, as shown here no bigger than a baby’s pinky nail, to furnish other growers, along with microalgae to feed the infant cultures; he also raises oysters to maturity, with several different lines, including Moon Dancers, a personal favorite. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

At Mook Sea Farm, Bill Mook raises oyster seed, as shown here no bigger than a baby’s pinky nail, to furnish other growers, along with microalgae to feed the infant cultures; he also raises oysters to maturity, with several different lines, including Moon Dancers, a personal favorite. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

But going from ancestral Wabanakis harvesting wild oysters, enjoying a feast, and perhaps drying the leftovers for their winter pantries to a modern oyster farm requires a leap of the imagination. Take Mook Sea Farm in Walpole, for instance, where Bill Mook produces five different types of oysters (including my personal favorite, Moondancers), as well as juvenile seed for other growers, along with the microalgae that make up feed for the oyster nursery. Guaranteed to be disease-free and disease-resistant, the spawn is produced in situ as an infinitesimal oyster egg, then nurtured through all its growing stages, from larva to spat, until it is recognizably a miniature oyster.

Spending time with Mook at his Damariscotta River farm is a little like spending time with an eager adolescent showing off his latest, totally complicated Lego project. We went through buildings, climbed up and down stairs, followed water pipes, looked at big containers of pristine river water, and examined test tubes, mesh socks, and clear plastic silos filed with tiny shells, all with the goal of educating me about the life cycle of an oyster. It’s hard to believe Bill Mook has been in this business for 35 years. He still bubbles with enthusiasm for everything, including, he emphasized, building resilience to the inevitable climate changes, many of which are upon us even now. “Every challenge is an opportunity,” he said. “Problems are really the raw material for innovation. There are huge opportunities here for Maine to be a leader, not just in policy but in technical innovation as well. That’s why I stay so optimistic.

A tray of five or six different locally raised oysters, served up at the Shuck Station in Newcastle (Damariscotta’s little sister). Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

A tray of five or six different locally raised oysters, served up at the Shuck Station in Newcastle (Damariscotta’s little sister). Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Special Report: Aquaculture in Maine

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.