From Whence We Came - Issue 103

Issue 103

By Peter H. Spectre

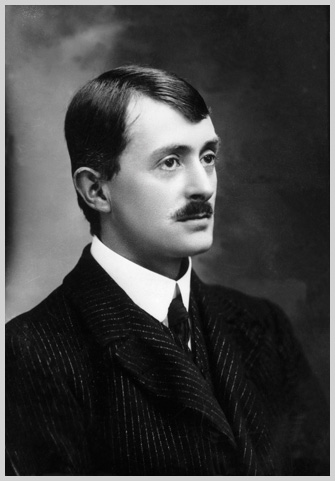

John Masefield, England's poet laureate, as a young man. We continue our series of short biographical sketches, remembering those who influenced how we respond to boats, ships, and the sea.

John Masefield

Sea poet laureate

Perhaps the most acclaimed author of poetry of the sea, John Edward Masefield (1879-1967) achieved that recognition with his poem “Sea Fever.” With an unforgettable opening line—“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky”—and several other lines and phrases that have been used in other works and titles of works by other writers, it is easily the best literary evocation of man’s romantic fascination with the sea. Like most successful writers, Masefield wrote about what he knew, and what he knew about the seagoing life he learned as a student aboard the English schoolship HMS Conway and as a young man aboard merchant ships under sail. Born and raised in England, he spent several years in the United States before returning to his home country and becoming a poet and novelist. His best book of sea poetry was his first, Saltwater Ballads; his best novel with a nautical theme was The Bird of Dawning; his best book of sea stories was A Mainsail Haul. His anthology of sea poetry by other writers, A Sailor’s Garland, is a superb collection. Masefield was named England’s Poet Laureate in 1930 and served in that position until his death in 1967.

Here, in an example of the poetry of prose, is part of John Masefield’s description of sailing in a square-rigger off the River Plate, from A Tarpaulin Muster:

“Over her bows came the sprays in showers of sparkles. Her foresail was wet to the yard. Her scuppers were brooks. Her swing-ports spouted like cataracts. Recollect, too, that it was a day to make your heart glad. It was a clear day, a sunny day, a day of brightness and splendour. The sun was glorious in the sky. The sky was of a blue unspeakable. We were tearing along across a splendour of sea that made you sing. Far as one could see there was the water—shining and shaking. Blue it was, and green it was, and of a dazzling brilliance in the sun. It rose up in hills and in ridges. It smashed into a foam and roared. It towered up again and toppled. It mounted and shook in a rhythm, in a tune, in a music. One could have flung one’s body to it as a sacrifice. One longed to be in it, to be a part of it, to be beaten and banged by it. It was a wonder and a glory and a terror. It was a triumph, it was royal, to see that beauty.”

Howard Irving Chapelle

Student of a vanishing past

Two books by Howard I. Chapelle (1901-1975) were instrumental in stimulating the small-craft revival that took hold in the United States beginning in the late 1960s— American Small Sailing Craft, and Boatbuilding. The former was a historical work describing and illustrating traditional watercraft from the colonial era forward; the latter was the most thorough work on wooden boatbuilding published to date (1941). All traditional boat enthusiasts worth their salt have a copy of each, or at least have them on their wish list.

A boat designer in his own right, Howard Chapelle’s principal occupation was historian of naval architecture. In that capacity, he served as head of the New England section of the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey, studied colonial ship design with the assistance of a Guggenheim fellowship, was Curator of Transportation at the Smithsonian Institution, and published a series of books on the evolution of ship design, among them The History of American Sailing Ships, The Search for Speed Under Sail, The Baltimore Clipper, and The American Fishing Schooners. The plans of many of the traditional boats being built today are either from the hand of Chapelle or were collected by him in an effort to keep them from being lost.

Anyone who entertains thoughts about building such a boat—or any boat, for that matter, or even a piece of furniture—should heed Chapelle’s recommendation:

“In every amateur boatbuilder’s shop,” he wrote in Boatbuilding, “there should be a ‘moaning chair’; this should be a comfortable seat from which the boat can be easily seen and in which the builder can sit, smoke, chew, drink, or swear as the moment demands. Here he should rest often and think about his next job. The plans should be at hand and here he can lay out his work. By so doing he will often be able to see mistakes before they are serious and avoid the curse of all amateur boatbuilders: starting a job before figuring out what has to be done to get it right.”

C.G. Davis

The forgotten man

Charles G. Davis is one of those men who were well known in their time and are nearly unknown today. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1870, he sailed around Cape Horn on a square-rigger as a young man, apprenticed with yacht designer William Gardner, worked in various boat shops, and then began designing boats and yachts on his own.

In 1898 he became the design editor of The Rudder, the leading yachting magazine of the day. During both world wars he was involved in the design and construction of wooden submarine chasers, PT boats, and minesweepers. In his later years, Davis became one of the preeminent professional American ship-model builders; many of his models are now in major maritime museum collections. All through his adult life he wrote articles for various yachting magazines and a series of books, illustrated with his own drawings and sketches, that are filled with authenticity of the sea. Among his many books are The Ways of the Sea, American Sailing Ships, The ABC of Yacht Design, The Built-Up Ship Model, and The Ship Model Builder’s Assistant.

“Charles G. Davis was the first to knock down much of the sham that creeps into print,” Weston Farmer wrote about a man he honored as one of his major influences. “The Davis gift of breathing life into drawings with a few slashes of India ink even today stands out to prove that true art is timeless.”

“In my youth,” C.G. Davis once wrote, “I was apprenticed to study naval architecture under a man fresh from a naval college, just starting in business, where everything was higher mathematics. I listened to him all day and then went home at night to where my future father-in-law, a practical shipbuilder, was doing the actual wood cutting and fastening. This was a combination of theory and practice that would be hard to beat. I once spent a Sunday morning in a City Island mould loft, at a shipyard whose proprietor was demonstrating to my naval architect employer that the moulded edge of a transom took on the curve he said it did, in contradiction to the way the architects’ plans had it drawn in—and the practical man proved his point.”

John Masefield, England's poet laureate, as a young man. We continue our series of short biographical sketches, remembering those who influenced how we respond to boats, ships, and the sea.

John Masefield

Sea poet laureate

Perhaps the most acclaimed author of poetry of the sea, John Edward Masefield (1879-1967) achieved that recognition with his poem “Sea Fever.” With an unforgettable opening line—“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky”—and several other lines and phrases that have been used in other works and titles of works by other writers, it is easily the best literary evocation of man’s romantic fascination with the sea. Like most successful writers, Masefield wrote about what he knew, and what he knew about the seagoing life he learned as a student aboard the English schoolship HMS Conway and as a young man aboard merchant ships under sail. Born and raised in England, he spent several years in the United States before returning to his home country and becoming a poet and novelist. His best book of sea poetry was his first, Saltwater Ballads; his best novel with a nautical theme was The Bird of Dawning; his best book of sea stories was A Mainsail Haul. His anthology of sea poetry by other writers, A Sailor’s Garland, is a superb collection. Masefield was named England’s Poet Laureate in 1930 and served in that position until his death in 1967.

Here, in an example of the poetry of prose, is part of John Masefield’s description of sailing in a square-rigger off the River Plate, from A Tarpaulin Muster:

“Over her bows came the sprays in showers of sparkles. Her foresail was wet to the yard. Her scuppers were brooks. Her swing-ports spouted like cataracts. Recollect, too, that it was a day to make your heart glad. It was a clear day, a sunny day, a day of brightness and splendour. The sun was glorious in the sky. The sky was of a blue unspeakable. We were tearing along across a splendour of sea that made you sing. Far as one could see there was the water—shining and shaking. Blue it was, and green it was, and of a dazzling brilliance in the sun. It rose up in hills and in ridges. It smashed into a foam and roared. It towered up again and toppled. It mounted and shook in a rhythm, in a tune, in a music. One could have flung one’s body to it as a sacrifice. One longed to be in it, to be a part of it, to be beaten and banged by it. It was a wonder and a glory and a terror. It was a triumph, it was royal, to see that beauty.”

Howard Irving Chapelle

Student of a vanishing past

Two books by Howard I. Chapelle (1901-1975) were instrumental in stimulating the small-craft revival that took hold in the United States beginning in the late 1960s— American Small Sailing Craft, and Boatbuilding. The former was a historical work describing and illustrating traditional watercraft from the colonial era forward; the latter was the most thorough work on wooden boatbuilding published to date (1941). All traditional boat enthusiasts worth their salt have a copy of each, or at least have them on their wish list.

A boat designer in his own right, Howard Chapelle’s principal occupation was historian of naval architecture. In that capacity, he served as head of the New England section of the Historic American Merchant Marine Survey, studied colonial ship design with the assistance of a Guggenheim fellowship, was Curator of Transportation at the Smithsonian Institution, and published a series of books on the evolution of ship design, among them The History of American Sailing Ships, The Search for Speed Under Sail, The Baltimore Clipper, and The American Fishing Schooners. The plans of many of the traditional boats being built today are either from the hand of Chapelle or were collected by him in an effort to keep them from being lost.

Anyone who entertains thoughts about building such a boat—or any boat, for that matter, or even a piece of furniture—should heed Chapelle’s recommendation:

“In every amateur boatbuilder’s shop,” he wrote in Boatbuilding, “there should be a ‘moaning chair’; this should be a comfortable seat from which the boat can be easily seen and in which the builder can sit, smoke, chew, drink, or swear as the moment demands. Here he should rest often and think about his next job. The plans should be at hand and here he can lay out his work. By so doing he will often be able to see mistakes before they are serious and avoid the curse of all amateur boatbuilders: starting a job before figuring out what has to be done to get it right.”

C.G. Davis

The forgotten man

Charles G. Davis is one of those men who were well known in their time and are nearly unknown today. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1870, he sailed around Cape Horn on a square-rigger as a young man, apprenticed with yacht designer William Gardner, worked in various boat shops, and then began designing boats and yachts on his own.

In 1898 he became the design editor of The Rudder, the leading yachting magazine of the day. During both world wars he was involved in the design and construction of wooden submarine chasers, PT boats, and minesweepers. In his later years, Davis became one of the preeminent professional American ship-model builders; many of his models are now in major maritime museum collections. All through his adult life he wrote articles for various yachting magazines and a series of books, illustrated with his own drawings and sketches, that are filled with authenticity of the sea. Among his many books are The Ways of the Sea, American Sailing Ships, The ABC of Yacht Design, The Built-Up Ship Model, and The Ship Model Builder’s Assistant.

“Charles G. Davis was the first to knock down much of the sham that creeps into print,” Weston Farmer wrote about a man he honored as one of his major influences. “The Davis gift of breathing life into drawings with a few slashes of India ink even today stands out to prove that true art is timeless.”

“In my youth,” C.G. Davis once wrote, “I was apprenticed to study naval architecture under a man fresh from a naval college, just starting in business, where everything was higher mathematics. I listened to him all day and then went home at night to where my future father-in-law, a practical shipbuilder, was doing the actual wood cutting and fastening. This was a combination of theory and practice that would be hard to beat. I once spent a Sunday morning in a City Island mould loft, at a shipyard whose proprietor was demonstrating to my naval architect employer that the moulded edge of a transom took on the curve he said it did, in contradiction to the way the architects’ plans had it drawn in—and the practical man proved his point.”

Peter H. Spectre is the editor of this magazine, the author of many books and magazine articles, and the creator since 1992 of The Mariner’s Book of Days desk diary and calendar.

John Masefield, England's poet laureate, as a young man.

John Masefield, England's poet laureate, as a young man.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.