Calling At Ash Island For Mixed Cargo

The crunching of my car wheels through the thin ice on the dirt road’s unavoidable puddles reminded me that this was early winter—a bit late in the season for exploring the Maine coast in the tiny canoe tied on the roof. But the crystal-clear northwest wind was merely warning of the cold to come, not bringing it, so I launched my diminutive vessel (length, 12 feet; displacement, 27 pounds) beside an old stone dock at Cushing Point at the mouth of the Weskeag River.

I propel my tiny canoe from a comfortably braced sitting position with a paddle that has a blade on each end. It is a fascinating way to travel—every ripple makes known its presence, and a whitecap is an adventure. All is quiet as I slip along. Most seabirds let me come quite close before they get nervous, and lovers in secluded spots along the shore give startled looks (followed by wide grins) when they discover that they are no longer quite alone.

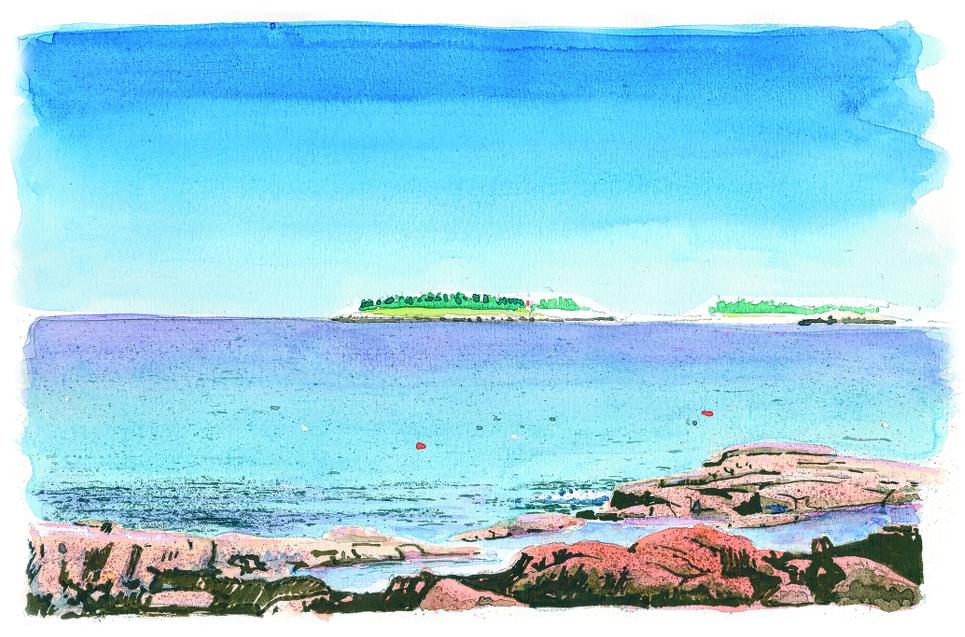

On this day, I paddled to Ash Island, a small, uninhabited piece of real estate that lies a scant 100 yards off Ash Point. I felt a bit like Samuel de Champlain, who fooled around on these shores in 1604, as I stood on the curved tip of sand on the island’s landward side and watched the swirling tide that continued to carve it. Then I put the little boat on my hip, trudged up the beach above the high tide line, and tucked her into the brownish green beach grass. The canoe’s tan skin blended in nicely.

Illustration by Ted Walsh

I began to circumperambulate the island: plenty of sharp-edged chunks of granite ledge to scramble over or around and plenty of beach pebbles and boulders, worn round by waves or glacier. It’s not the sort of walking I can do with my hands in my pockets. If I want to look anywhere but where my next step is about to land, I have to stop.

Illustration by Ted Walsh

I began to circumperambulate the island: plenty of sharp-edged chunks of granite ledge to scramble over or around and plenty of beach pebbles and boulders, worn round by waves or glacier. It’s not the sort of walking I can do with my hands in my pockets. If I want to look anywhere but where my next step is about to land, I have to stop.

There is so much to keep track of. Stop to see how the shape of the island is changing. Stop to peer into the interior spruce forest, knowing it won’t reveal much, but afraid to miss something. Stop to watch the waves wash in against the rocks. Stop to scan the horizon for boats. Stop to beachcomb.

Ah, the beachcombing.

The flotsam that has washed up on the shore of an island tells the story of the place, and seems as personal as a signature. Ash Island spun a few yarns the day I was there.

First, there is driftwood. I am finicky about which pieces I pick up to use for carpentry or firewood. They cannot be too big since my tiny canoe does not have much room for cargo. The carpentry pieces must be perfect, without cracks, knotholes, or irregularities of any kind. My little Franklin stove cannot swallow a stick more than 12 inches long, so I don’t pick up any driftwood longer than that for firewood.

It was obvious almost immediately that there would be considerably more driftwood that met my standards for carpentry and firewood than I would be able to carry. The plenitude presented a nice problem: how to select and carry the right pieces so that the completion of the walk coincides with a full load—no more, no less—and so that if a really first-class piece of driftwood is discovered near the end of the trek, there will be room for it in my arms or jacket pockets without having to discard a lesser piece carried needlessly nearly the whole way round. Life is not as simple on Ash Island as one might think. I decided to hedge my bets and place my selections atop prominent rocks instead of carrying them. When I got around, I’d come back against the way I went with a clear idea (if memory serves) of which pieces I should retrieve and which scorn.

The author does his exploring in a small Sugar Island Canoe, like the one shown here being paddled by its designer Bart Hathaway. Photograph courtesy Roger Taylor

The author does his exploring in a small Sugar Island Canoe, like the one shown here being paddled by its designer Bart Hathaway. Photograph courtesy Roger Taylor

A little further around the shore and another complication set in. There, nestled among the sea wrack, was a large, wooden wedge of obvious beauty and utility. It would certainly have to become part of my cargo, and it represented a new category that was not wood for carpentry exactly, and certainly not firewood. I placed the wedge in a prominent position against my return.

I chanced upon a bit of plank-on-frame, painted white on the outside— clearly part of the bow of a boat. When I see evidence of the very bow of a boat that has failed, I sense tragedy. I shuddered.

The next cargo category to make its appearance was clothing. I found a plain white sunshade that looked as if it belonged on a tennis court. Plain headgear is a rare find these days; most hats that wash up on the shore are adorned with advertising for a beverage, a sports team, or a minor enthusiasm. Normally I wouldn’t go trying on someone else’s hat, but this one had been scoured by the sea. The shade fit perfectly without disturbing the corroded buckles, so it went into a jacket pocket, saved for a warmer season.

I found tableware—a white plastic mug, jammed into a rocky crevice. I worked it loose for inspection and was rewarded: on the bottom, raised letters spelled out “Designer Collection by David Douglas Reg. (signature) Pat. Pend. Made of Genuine MG Accalac Reg.” Nothing unusual about this mug except its label, and even that would be hidden when the thing was in use. Still, it didn’t look as if it would leak, and it fit perfectly into another pocket.

Continuing alongshore, I ran into a treasure trove of lobster buoys and grabbed two white ones and left a dark red one. Occasionally, I find a buoy with pot warp long enough to be worth salvaging. On one of these buoys, there was a good ten feet of handsome white Dacron line, the sort usually found on a yacht. It took ten minutes or so for me to worry it out of the clefts in the rocks where the sea had crammed it, and then to work loose the plethora of hitches that secured it to its buoy. A rare find, this expensive piece of chandlery merchandise. In it went with the tennis visor.

The buoys were located almost where I’d come ashore, so I turned about and started back the way I’d come. Now I travelled faster, just thinking about finding my cargo displays, rather than scanning for new finds.

I thought I’d missed my wedge, really the prize piece of all, and stood teetering on a boulder, wondering whether to press on or retrace my steps. Ah, but then there it was, much farther along than I’d thought. Satisfying. Regaining the tiny canoe, I dumped my armload of gleanings into the cargo hold behind the backrest, along with the contents of my pockets. Shoving off toward the mainland, I wondered if anybody would set foot on Ash Island again before next spring. Well, maybe I’d come back myself.

As I came ashore to haul out near the car, a stranger greeted me. The tiny canoe had aroused his curiosity.

“You been out?”

“Yup.”

“Now that’s sport.”

I left it at that, not wishing to reveal the practical aspects of my mixed cargo from Ash Island.

Roger C. Taylor has been a leader at the U.S. Naval Institute and at International Marine Publishing Company, Camden, Maine, and a teacher of sailing and seamanship at the U.S. Naval Academy and WoodenBoat School. Among the many vessels he has captained besides his tiny canoe are two replicas in the fleet of the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. His seven published books include the Good Boats series and The Elements of Seamanship. The first volume of his two-volume biography of L. Francis Herreshoff will be published in November by the Mystic Seaport Museum. Taylor and his wife, Kathleen

Carney, live on a Dutch steel powerboat in France.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.