A Sailing Misadventure

Lessons learned from high winds and a swamped boat

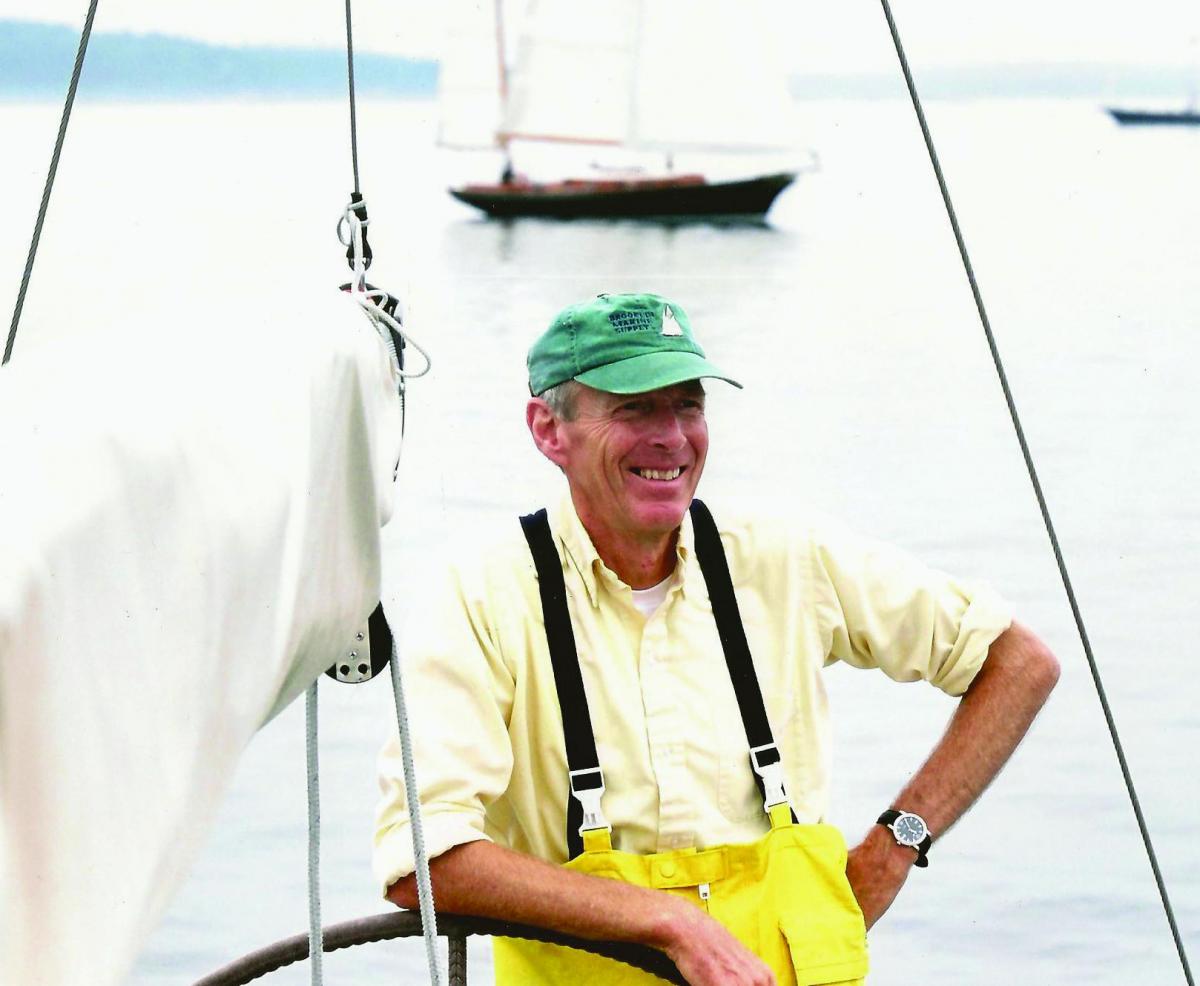

Ben Emory, at the helm of his Finngulf 391 West Wind, is an experienced sailor. But he learned a few important lessons after a harrowing spring sail on his Cape Cod Bulls-Eye. Photo by Jamie Schapiro

A Cape Cod Bulls-EyE is one tough sailboat. Built in fiberglass to the same hull design as a Herreshoff 121⁄2, the boat has exceptional capability for a 15-foot daysailer. Yet, one life-threatening Memorial Day outing on Eggemoggin Reach taught me that years of sailing such craft had led to overconfidence in what the design—and I—could handle safely.

Ben Emory, at the helm of his Finngulf 391 West Wind, is an experienced sailor. But he learned a few important lessons after a harrowing spring sail on his Cape Cod Bulls-Eye. Photo by Jamie Schapiro

A Cape Cod Bulls-EyE is one tough sailboat. Built in fiberglass to the same hull design as a Herreshoff 121⁄2, the boat has exceptional capability for a 15-foot daysailer. Yet, one life-threatening Memorial Day outing on Eggemoggin Reach taught me that years of sailing such craft had led to overconfidence in what the design—and I—could handle safely.

Reaching southeastward along the Deer Isle shore in 10 knots of southwest breeze in my Bulls-Eye Nugget, I savored the warmth and the easy tug of the tiller. Then the wind shifted suddenly to the northwest. In an instant I was sailing downwind in a noticeably increasing breeze.

Getting back to Center Harbor would be a hard thrash, with reefing essential. I checked my watch, worried about being home in time for an especially important conference call. Conditions were getting too wild to reef in mid-channel—easier to continue to the WoodenBoat mooring field and reef there. Nugget tore along on a fun sleigh-ride, although gusts now close to 30 knots were worrisome. WoodenBoat’s moorings are relatively exposed in a hard northwester, but I secured a mooring on my first pass as Nugget pitched madly and sails thundered. I lowered the sails, temporarily safe. The wind seemed slightly less, and there was still time to sail home for the scheduled telephone call, a call that was impairing my judgment and safety.

Bulls-Eyes are easy to reef. The boom slides off the mast, and the mainsail rolls around it like a window shade. I put in four rolls, more than ever before.

Under now-overcast skies, and with the water a hard, white-capped gray, I started toward home, which was a couple of miles upwind. Pleased with how well Nugget was handling the challenging conditions, I kept my weight as far outboard as possible. Spray blasted me as I feathered into the wind and luffed as necessary to minimize the heel angle and water slopping over the leeward coamings. On we plunged.

The wind increased more. The boat struggled and the water’s surface turned white as wave tops blew off. Perhaps I let down my guard for a second. Suddenly, the lee rail was under water and going deeper fast. I jammed the tiller to leeward in a frantic effort to come upright, but, sickeningly, I knew it was too late. Nugget was awash, with no way to bail because the boat was floating full of water at a 45-degree angle with the leeward coaming submerged.

I had two immediate thoughts: get the sails down, and will the boat stay afloat? Wondering how long we would float had to wait while I dealt with sails. The halyards were cleated at the base of the mast, now far under water. I did not relish a swim in the cold springtime water and its implications for hypothermia, but the sails had to be dealt with. I slid into the water, reached down, uncleated the halyards, and was back on the rail within seconds. I pulled the sails down, but the wind immediately blew the jib halfway up the headstay again. Moving fore and aft to tie up the sails was too risky. Going aft for the sail ties submerged the stern; moving toward the bow and the jib put the bow way down. I was going to have to perch on the rail on the high side, out of the water as much as possible, and let come what might.

“Ben, you are in a predicament!” I remember repeating to myself. There were no other boats visible—and late on such a windy May afternoon none were likely to appear. While I could see houses, they were mostly empty summer homes. Even if someone looked out, the boat and little white jib blowing in the wind would be hard to spot.

Nugget has buoyancy tanks. I had to will the possibility of leaks in those tanks out of my mind. I analyzed self-rescue possibilities. The outgoing tide was carrying me toward the Reach’s main channel. The wind direction was across the current. I might blow onto an island to leeward if the current did not lock me in its grasp. With the boat so full of water, I saw little hope of affecting the direction of travel, but if I passed close enough to an island to leeward, I could attempt to use the submerged rudder and the partly raised jib to try to steer onto the shore. The first island to which I might blow has a house and fireplace, perhaps even a working telephone. If I missed that and then blew near the two islands farther out, I might get ashore but have no place to get warm. For the moment, all islands were too far away. I mulled my fate, recognizing the irony in being so at risk in home waters in a small sailboat that I have sailed endlessly and that is known for its seaworthiness.

I never saw the yawl Katrinka approaching under power until she loomed close ahead. She steered inches from my windward side as two strong crew members stood by her lifelines. I put my feet on Nugget’s rail and leapt. Both of my outstretched arms were grabbed, and I was hauled over her lifelines—safe and astounded.

Stammering heartfelt thanks, I introduced myself. Unfamiliar with the waters, Katrinka’s crew had been powering around looking for a place to shelter. They told me that their anemometer showed the wind gusting to 35 knots.

They immediately expressed concern about Nugget’s fate. Katrinka’s professional captain was willing to try to tow her. I demurred. Katrinka’s newly painted topsides and varnished rail were immaculate. I wanted no responsibility for risking their beautiful boat.

We turned away seeking shelter. Watching Nugget fall astern, I saw how difficult she was to see as the distance increased and I realized that the current would probably sweep her into Jericho Bay. Had I not been rescued, I might not have been spotted, nor would I have passed close enough to an island to get ashore.

The captain continued to think about trying to tow Nugget. With evidence of decreasing wind strength I finally relented. Back we powered. Using Katrinka’s dinghy, the captain and I passed a towline around Nugget’s mast. At a snail’s pace, we turned toward the WoodenBoat mooring area. There, the crew took me ashore to my wife, Dianna, who had been alerted by cell phone. The seamanship and hospitality of Katrinka’s people were just outstanding. In their absence I do not know what would have happened to me.

Ben Emory is a lifelong sailor who splits his time between Salisbury Cove and Brooklin. When not on the water, he has spent decades actively involved in Maine land conservation.

Lessons Learned

Endless learning is a wonderful part of sailing’s pleasure. The near catastrophe described in the accompanying article about the swamping of a Cape Cod Bulls-Eye reminds all mariners of the following lessons:

- Be current on the weather forecast. Do not rely on what one thinks one heard the previous day, especially in early- and late-season sailing when conditions may be more changeable and harsher.

- No matter how much experience and confidence one has in a boat, remain realistic about its limitations.

- Do not let judgments about safety be clouded by other obligations, such as the “important” scheduled telephone call that preoccupied the author.

- If one does not usually wear a life jacket, be sure to wear one when you are sailing alone, especially when conditions turn dicey.

- Take a portable VHF radio with you, preferably in a waterproof bag.

- Tell someone where you are going and when you expect to return.

- Even deeply reefed sails and small jibs can be too big to be safe when the wind howls.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.