Maine Muse

Painter Alexandra Tyng captures the coast from above

Alexandra Tyng finds inspiration for her paintings by looking at the landscape from the air. Courtesy Gross McCleaf Gallery

Alexandra Tyng finds inspiration for her paintings by looking at the landscape from the air. Courtesy Gross McCleaf Gallery

A chance visit to Maine led to a lifetime connection for painter Alexandra Tyng, who is known for her luminous aerial views of the state’s coast, as well as for portraits of her friends, family and distinguished professionals.

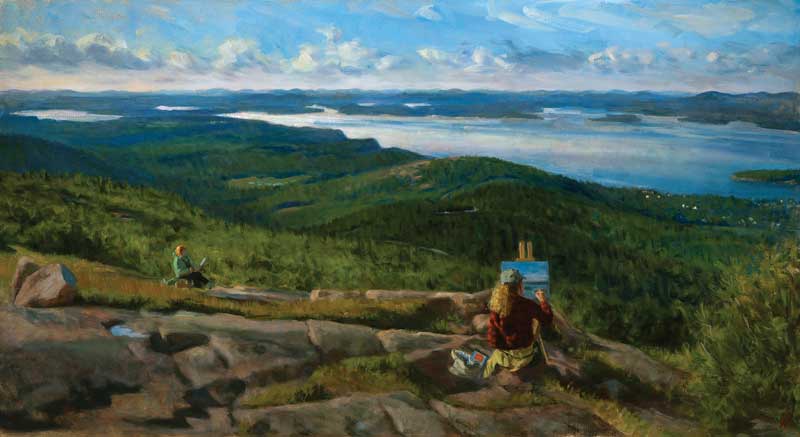

Alexandra Tyng painting in Baxter State Park, 2014. Photo by Bryant Davis

The story begins in the summer of 1967, when her architect mother, Anne Tyng, loaded up the family’s Volkswagen camper and set off from Philadelphia with then 13-year-old Alexandra and headed for Montreal and the International and Universal Exposition. Anne Tyng wanted to see the architecture, including Moshe Safdie’s famous futuristic housing complex, Habitat ’67.

Alexandra Tyng painting in Baxter State Park, 2014. Photo by Bryant Davis

The story begins in the summer of 1967, when her architect mother, Anne Tyng, loaded up the family’s Volkswagen camper and set off from Philadelphia with then 13-year-old Alexandra and headed for Montreal and the International and Universal Exposition. Anne Tyng wanted to see the architecture, including Moshe Safdie’s famous futuristic housing complex, Habitat ’67.

On the way home, they drove east to the coast of Maine, to Mount Desert Island. Anne wanted to know more about her family’s genealogy. Her great-grandparents had been islanders: Benjamin Franklin Atkinson, a schoolteacher, and his wife and former student, Harriet Seavey. Seavey’s sister Rebecca married a member of the Somes family, creating a connection to one of the island’s founding families.

The visit began a tradition of summers spent on Mount Desert Island. The Tyngs fell in love with Long Pond, the four-mile-long glacier-made body of water that stretches north-south, with its ends in Somesville and Southwest Harbor. A camp on the pond proved the perfect getaway from summer in Central City, Philadelphia.

During that first visit, Alexandra met a Somes cousin, Diana Cobb Ansley. They became fast friends—and future plein air painting pals. Years later, Ansley recounted how Alex helped her start painting by providing a list of basic oil paints, “written on a napkin in a diner in Philadelphia.”

Event Horizon, oil on linen, 2014, 46" x 66". Tyng’s narrative work often has an allegorical quality, as in this painting of night sky gazers on Indian Island. Opposite page: Courtesy the author. Private Collection

Event Horizon, oil on linen, 2014, 46" x 66". Tyng’s narrative work often has an allegorical quality, as in this painting of night sky gazers on Indian Island. Opposite page: Courtesy the author. Private Collection

Alexandra Tyng began painting around Mount Desert Island early on. Her father, the renowned architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974), who was himself an avid plein air pastel painter, provided her with various art supplies, including a lap easel. “He always had tubes of tempera paint in his office,” she recalled, and she took them to Maine. Among her first paintings was a view from the Kimball Camp dock, the first of several settings of family retreats on Long Pond.

Tyng has been fascinated by Indian Island Light in Rockport Harbor, which has appeared in several of her paintings. This is Peaked Shadow, oil on linen, 2012, 26" x 22". This page: Image courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery

When it came time for college, Tyng opted for an academic education over art school. She ended up at Harvard College where she majored in art history and minored in psychology. She loved going to area museums to study the Masters, and was especially drawn to several John Singer Sargent paintings, including El Jaleo at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The image of the Spanish Gypsy dancer made a profound impression on her that has lasted to this day: One of her recent canvases, Triumph of Light, features what she calls a “little nod” to the painting, emulating its compositional rhythm by way of a line of musicians seated in the middle ground. Sargent’s dancer is replaced, as it were, by a young man leaping over a bonfire. The inspiration was a solstice party at a friend’s house overlooking the Schuylkill River.

Tyng has been fascinated by Indian Island Light in Rockport Harbor, which has appeared in several of her paintings. This is Peaked Shadow, oil on linen, 2012, 26" x 22". This page: Image courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery

When it came time for college, Tyng opted for an academic education over art school. She ended up at Harvard College where she majored in art history and minored in psychology. She loved going to area museums to study the Masters, and was especially drawn to several John Singer Sargent paintings, including El Jaleo at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The image of the Spanish Gypsy dancer made a profound impression on her that has lasted to this day: One of her recent canvases, Triumph of Light, features what she calls a “little nod” to the painting, emulating its compositional rhythm by way of a line of musicians seated in the middle ground. Sargent’s dancer is replaced, as it were, by a young man leaping over a bonfire. The inspiration was a solstice party at a friend’s house overlooking the Schuylkill River.

Encouraged by her parents but essentially on her own, Tyng chose to pursue art. She developed into an accomplished painter, largely self-taught, learning from looking, and also from spending time with fellow artists. When her children, Julian and Rebecca, were little, she mostly put painting aside. After they had grown up, she returned to the easel with a pent-up passion. And she took to the landscape: “Plein air painting,” she told critic Stephen May, is “my source of ideas, and a way of keeping my brushstrokes fresh and my color sense accurate.”

A recent trip to Baxter State Park that included an airplane flyover of Katahdin resulted in Cirque, oil on linen, 2015, 44" x 54". This page: Image courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery

A recent trip to Baxter State Park that included an airplane flyover of Katahdin resulted in Cirque, oil on linen, 2015, 44" x 54". This page: Image courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery

Tyng has specialized in aerial views, hiring small airplanes and, occasionally, a helicopter to fly over various landscapes. She is not especially fond of flying, but motivation to view the world from the air helps her overcome her fear. “I like seeing the forms of the land,” she says, “to understand it from different perspectives.” She has done a number of aerials of Mount Desert and loves the revelations that happen when seeing the links between mountains, valleys, lakes, and streams.

During these flights, Tyng takes photographs, looking for configurations that have interesting foregrounds and diagonals “that draw your eye back into the space.” In the studio she studies the photos and develops the composition using several different images. In the case of Monhegan, she was unable to find someone to fly her over the island (“too far away, can’t land, too risky” were the excuses). So she decided to work from a photograph by Charles Feil, who specializes in aerial photography. She took some artistic license with his image, including changes in some of the coloring, but it is true to the view.

For some years, Tyng has been part of a loose-knit group of plein air painters who call themselves the Maine Landscape Guild. They select a landscape and paint it together. Two of the members, Ansley and Nancy Bea Miller, are pictured before their easels in Tyng’s The Porcupines from Cadillac.

Recently, Tyng, Ansley, and a few other painter friends made a pilgrimage to Mount Katahdin. They hired a guide to take them to spots they had identified in David Little’s book Art of Katahdin that promised good plein air possibilities. Tyng also arranged to fly over the mountain, which led to the painting Cirque, a handsome rendering of the massive amphitheater that is among Katahdin’s most notable features.

The camps on the shores of Long Pond are another favorite subject. Tyng loves the rustic architecture and has painted lakefront cabins and the activities that go along with them: lighting sparklers on the dock, washing dishes al fresco with boiling water, carrying firewood, canoeing, or simply sitting and enjoying the view.

Tyng has also found long-time inspiration on Indian Island just off the eastern edge of Rockport Harbor—the island is owned by her half-brother’s family. The lighthouse, a four-sided brick structure first built in 1850, appears in several of her paintings, sometimes as a subject in and of itself, and sometimes as a setting for a narrative, as in the painting Outside/Inside, a double portrait of her half-brother, Nathaniel Kahn, as a 20-year-old and as an adult standing in the lantern room at the top of the tower.

Among Tyng’s most recent Indian Island paintings is Event Horizon, which shows a group of people, young and old, looking up at a black hole in the night sky, their faces reflecting a mix of feelings, from curiosity to fear. The title is a term from general relativity connoting the point of no return. The painting, which Tyng considers a kind of allegory for our current worries, recalls the illustrations of some of her early heroes, including N.C. Wyeth, but also displays a kinship with the narrative work of contemporary painters like Bo Bartlett and Vincent Desiderio.

When Tyng isn’t painting the landscape, she is apt to be working on a portrait. She has become a sought-after portrait painter, winning a number of honors in the field. She approaches each commission as “a new adventure” and considers them collaborations with her subjects. She will interview the individuals to learn about them and their hopes for the portrait. She collects visual information—sketches and photographs—and then paints them from life in order to capture expression and color notes.

Tyng’s portrait gallery includes doctors, educators, musicians, and architects, as well as friends and family. She has painted likenesses of both her parents. The portrait of Anne Tyng (1920-2011) is in the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania; that of her father, Louis Kahn, in the National Portrait Gallery.

In a letter written to Anne in Rome shortly after Alexandra was born, Kahn mused on his daughter’s looks. “She must be certainly beautiful if she looks the slightest bit like you,” he wrote, adding, “If she is like me she may grow to become beautiful in other ways.” And then he made a prophetic suggestion: “If she has your wonderful ability and courage, she will love to live and work in the creative field of the ever fascinating universe.” And so it was, and so it is.

Carl Little’s latest book is Philip Barter: Forever Maine (Marshall Wilkes). Alexandra Tyng’s painting Jet Stream is on the cover of his and his brother David Little’s book Art of Acadia.

For More Information

Alexandra Tyng is represented by Dowling Walsh in Rockland, Maine, gWatson Gallery in Stonington, Maine, and Gross McLeaf Gallery in Philadelphia. Her unconventional early family life is highlighted in Nathaniel Kahn’s 2003 documentary “My Architect: A Son’s Journey.”

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.