Writer's Retreat

Photographs by Dave Clough

A journalist in Maine will spend years turning copy on a dime, writing at coffee shop tables, in cars during raging storms, at town meetings, or on boats in the middle of Penobscot Bay.

It’s a skill helped by technology and a dose of adaptability. Ernest Hemingway recognized that being a newspaperman early on had been fundamental to his evolution as an author. Constructing concise sentences, while presenting a passel of facts and details, on deadline, is no small feat. But quality of space does matter to writers, just as it does for artists and artisans. Virginia Woolf articulated in her seminal 1929 talk/essay, “A Room of One’s Own,” that women needed “a room” and “room” for the imagination to flourish.

The studio originally was designed to nestle closer to the contour of the slope, but the team agreed on the need for more headspace in the garden/ tool shed below. With no granite ledges in the way, excavator Bruce Colson dug a little deeper, resulting in ample 6-foot clearance in the shed.

The studio originally was designed to nestle closer to the contour of the slope, but the team agreed on the need for more headspace in the garden/ tool shed below. With no granite ledges in the way, excavator Bruce Colson dug a little deeper, resulting in ample 6-foot clearance in the shed.

E.B. White’s boathouse, where he wrote while in Brooklin, Maine, illustrates the power of pensive surroundings on the creative act. In a well-known photo, he is there, seated at a simple table with a typewriter at his fingers. To his right, a window opens to a broad vista stretching to the sea.

So at the age of 57, I concluded that if I were ever to get serious about writing (truly writing!) then a dedicated space was necessary. And that did not mean a quiet carrel at the library, or a desk in the bedroom. I called accomplished Camden architect Rosie Curtis, whose path I had crossed many times at dance parties, planning board meetings, and potluck suppers. She came over to the Rockport home that my husband and I purchased in 1993, on three acres of fertile Goose River alluvial soil. Quietly, she stood, analyzing the slope of the wooded hill and the particular view I wanted from the studio—a sweep over grass to a flower garden, a giant white pine and back toward the vegetable garden—a scene that embodies the Maine landscape, half cultivated, half scruffy, but which soothes our souls no matter the season.

Subdued light pours into the studio all day long, enhancing the warmth of the oak floors and gracefully weaving the indoors with the outdoor landscape.

Subdued light pours into the studio all day long, enhancing the warmth of the oak floors and gracefully weaving the indoors with the outdoor landscape.

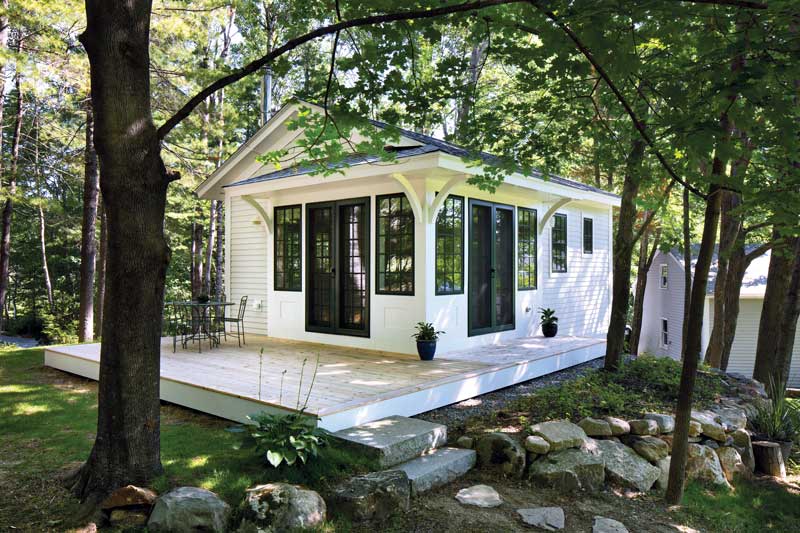

Wheels turned quickly in her head; she had already been developing the prototype of a tiny house in her portfolio and she envisioned a modification of it here, a 16- by 24-foot building whose roofline would blend in with existing structures.

“Sensitive siting was paramount,” said Curtis. “It took three meet-ings among the trees to minimize how many would need to be felled, to maximize the views and bring the new studio into the right relationship with the existing house and garage.”

We bounced creatively off each other, as is required in a good relationship with any architect. I said French doors, many of them; she said, there’s only so much wall space.

I said casement windows everywhere; she said, absolutely. Bathroom? Very small. Rinnai heater? Okay, but a wood stove, too. Then, the flourishes: A wide overhang over the French doors, decorative brackets on the eaves, “contributing to the sense of a sheltering roof,” said Curtis, and a window and barn doors on the garden shed directly below.

The writer at her desk. Photo courtesy Courtney Newman

The writer at her desk. Photo courtesy Courtney Newman

“The studio is a sanctuary of peace and quiet that is crafted to encourage immersion in the garden landscape,” she said. “The space has been designed to invoke joy, both from the outside, looking in and the inside, looking out.”

We called Maine Coast Construction, and Mark DeMichele, who has been with the company since 1986, arrived. It was a dreary October aftenoon, but DeMichele and Curtis could see the possibilities. I had the notion of a desk and windows overlooking gardens. They had the expertise to pull off much more.

A small wood stove provides warmth and cheer in the cold winter months.

A small wood stove provides warmth and cheer in the cold winter months.

“When I first learned of Lynda’s idea to build a writer’s studio on her property, my thought was whether or not she was serious,” said DeMichele. “This was mostly a reaction because we were busy and, at the time, I had not personally met her. Now, after working together along with Rosie, I realize that when Lynda has an idea, she becomes focused. It also became quickly apparent that both Rosie and Lynda have an appreciation and respect for tradespeople, which sets a particular tone in the working relationships right from the beginning.”

A project intention was set: There was to be no undue pressure, no irritated phone messages, and no deadlines, other than spring 2018… sometime.

And magically, the project flowed. Bruce Colson, owner of Colson Excavation and Landscaping, in Owls Head, is an artist with earth as his palette. As he shaped the landscape, we would stop the machines and gaze into holes, marveling at the geologic history presented in the strata of Rockport dirt.

With a sixth sense, he easily fitted rocks into place, complementing other rocks that curved gracefully into walls.

There were some debates. I chose wooden clapboards over fiber cement siding, although Curtis and DeMichele suggested the durability of newer synthetic materials would be more pragmatic.

Rockport fishermen and boatbuilder Kenny Dodge milled a cherry tree that was felled to clear space for the studio. The resulting boards will be used for benches. Photo courtesy Lynda Clancy

Rockport fishermen and boatbuilder Kenny Dodge milled a cherry tree that was felled to clear space for the studio. The resulting boards will be used for benches. Photo courtesy Lynda Clancy

For an additional expense, but not ridiculously so, we went with quarter sawn white oak flooring, which was beautifully created and laid by Shawn Gregory of Coastal Maine Wood Floors.

Liz Pooler, at Smith and May, suggested we install a small Squirrel wood stove, because the space was so small, “it will heat right up.”

And through the sub-zero January days, Foreman Eben Bucklin, and carpenters Kenny Robbins and Zach Nelson were at the site at 6:30 a.m., framing, roofing, and building with impeccable precision.

“The process of working with the contractors and owners throughout the construction process was organic and respectful,” said Curtis. “Everyone involved in the project cared about both the process and the end result.”

DeMichele echoed that sentiment: “The studio was thoughtfully designed and, in spite of the bitter cold winter, our crew enjoyed bringing the studio vision to reality. The few minor hiccups were worked out together, leaving this as one of those projects where the pieces just fit smoothly together. We are grateful to have been a part of it.”

In the end, the tiny house aspect embodied in this studio, albeit minus a kitchen, captivated craftsmen and visitors alike.

“I told my wife about this studio,” said one of the painters. “It has perfect dimensions. Why do we need anything bigger to live in?”

Lynda Clancy is Editorial Director of Penobscot Bay Pilot.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.