Zemphira

A modern new keel for an older racer

Zemphira (originally named Goshawk) was built in 2005 by Brooklin Boat Yard in collaboration with Rockport Marine. Photo by Alison Langley

Like many sailors with a decent racing record, I’ve been invited to sail aboard many fine yachts. For several summers this included a regular stint as tactician/mainsheet tender aboard Goshawk, a beautiful 76' wood/composite sloop designed by Bob Stephens and Paul Waring, and built in 2005.

Zemphira (originally named Goshawk) was built in 2005 by Brooklin Boat Yard in collaboration with Rockport Marine. Photo by Alison Langley

Like many sailors with a decent racing record, I’ve been invited to sail aboard many fine yachts. For several summers this included a regular stint as tactician/mainsheet tender aboard Goshawk, a beautiful 76' wood/composite sloop designed by Bob Stephens and Paul Waring, and built in 2005.

There wasn’t much unlovable about Goshawk. But one thing that gave a tactician pause—a concern shared equally by then day-captain John Maxwell—was her deep-draft keel: 10 feet, 9 inches. Maine’s waters are studded with rocks, and the water is opaque. You can’t eyeball a ledge anywhere near that deep.

Goshawk was originally designed for the Bermuda Race, so draft wasn’t a primary issue. But even way back then (2005) Bob Stephens was such a pro design engineer that a hard grounding entered into his calculations. Specifically, he used formulas provided by the American Bureau of Shipping to deal with toe-stubbing decelerations from full speed to a dead stop in just a quarter of a second. In engineering there is a category of scrutiny that is considered of the ultimate accuracy. It’s called “tested to destruction.” Stephens hoped this mathematical standard wouldn’t ever need testing, but he hoped for the best and ciphered for the worst.

The worst happened last summer, a high-speed grounding off Metinic Island. But that misfortune had a silver lining, as it gave Stephens and his firm a chance to redesign the boat’s keel and modernize the 15-plus-year-old boat. Sold to new owners and renamed Zemphira, the yacht had undergone an extensive refit at Lyman-Morse just before the grounding. Those improvements included a new rudder, more powered winches, burying the jib roller, and generally bringing a race-worn steed back to gleaming perfection. But the keel had remained untouched because of time constraints.

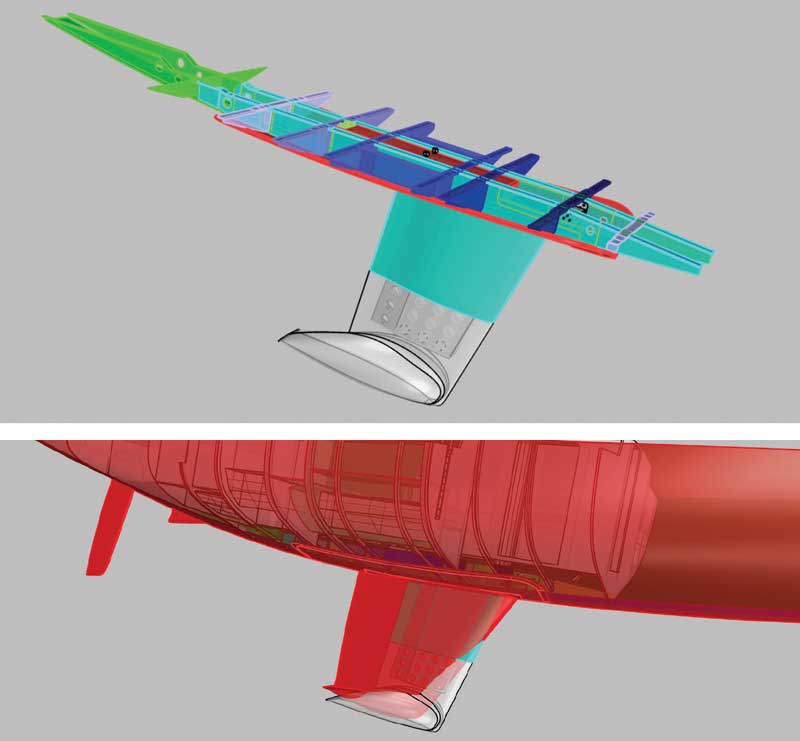

The bottom image shows Zemphira’s hull and original keel (in red), with the new keel (in gray and aqua). The replacement section of hull skin can be seen as the rectangular outline surrounding the original keel. The top image shows the keel socket and internal structure: remaining portion of original bronze frame (lime green), new carbon girders (light blue), and new carbon transverse floors (various shades of darker blue). The new keel has a lead cast bottom ( gray) and a steel strut with a fiberglass foil (aqua). Renderings courtesy Bob Stephens (2)

The bottom image shows Zemphira’s hull and original keel (in red), with the new keel (in gray and aqua). The replacement section of hull skin can be seen as the rectangular outline surrounding the original keel. The top image shows the keel socket and internal structure: remaining portion of original bronze frame (lime green), new carbon girders (light blue), and new carbon transverse floors (various shades of darker blue). The new keel has a lead cast bottom ( gray) and a steel strut with a fiberglass foil (aqua). Renderings courtesy Bob Stephens (2)

When Zemphira hit on her maiden voyage after the refit, the keel was smashed back, just as designed. A bit of bronze structure was bent but not broken; the fin stayed on; some wood cracked, but didn’t totally yield; the foam core in her hull skin remained intact; zero water came in; and the crew was able to get the boat back to Lyman-Morse where she was hauled. In other words, the original design prevented disaster.

When Stephens was consulted on how and whether to repair Zemphira, he came up with a plan for replacing the damaged portions of the hull and keel connection, and building a new keel. If all goes as planned, the modifications will result in a faster boat with little increase in her racing rating. In addition, the new system is designed in such a way that if the boat hits a rock at speed, the keel will swing back, absorbing impact forces and leaving the hull undamaged, making repairs less complicated.

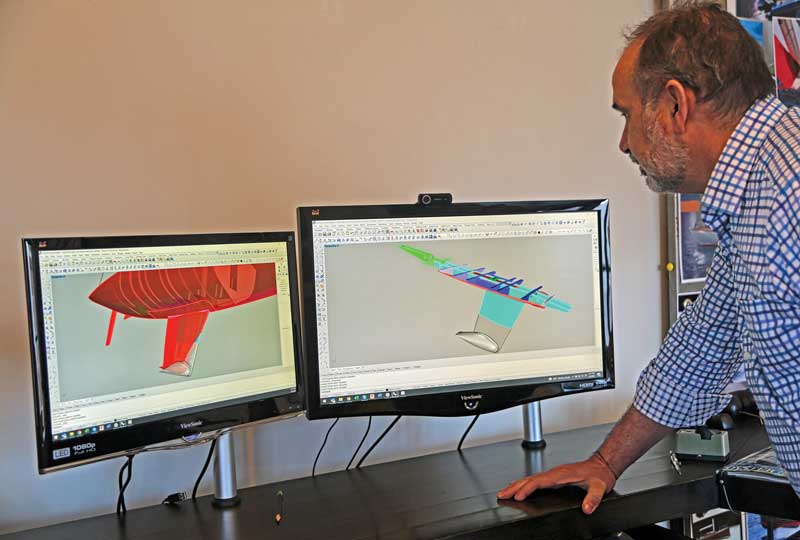

Bob Stephens explained that 3-D computer modelling is so precise that the designers were able to have elements of the keel built thousands of miles apart without worrying that they would not fit together. Photo by Art Paine

Bob Stephens explained that 3-D computer modelling is so precise that the designers were able to have elements of the keel built thousands of miles apart without worrying that they would not fit together. Photo by Art Paine

In addition to taking advantage of new technologies and modernizing a sleek racing boat, this method of redoing the keel and related hull components also will cost considerably less than simply rebuilding the original system, according to Stephens.

I always love to visit Bob at the Stephens Waring office in Belfast where his artwork and 3D computer virtuosity are on full display. Together, onscreen, we peeled away the layers of the new structure in and above Zemphira’s keel, which is designed to swing backwards but neither break nor drop off. Nor is it likely to suffer even the limited damage caused by the first encounter.

The old keel had bolts that attached the keel into bronze frames in the hull. In this new design, the keel fits precisely into a molded composite socket in the hull that can withstand the sideways strain that results when the boat heels. This required extremely precise engineering that only could be done with 3D computer modeling.

Using these precise measurements, Canadian company Mars Metals was able to weld a steel keel strut and socket plug, and to cast the lead ballast keel and bulb directly onto the bottom of the strut. The top of this structure will be fitted into the new carbon hull insert built by Lyman-Morse.

The new keel required stringent engineering to fit, and fold, beneath a wide flat floor in Zemphira’s elegant “living room.” Photo by Alison Langley

The new keel required stringent engineering to fit, and fold, beneath a wide flat floor in Zemphira’s elegant “living room.” Photo by Alison Langley

The original keel distributed strains throughout a bronze webwork, but the new keel is designed to absorb the stress of an impact by swinging backward. The upper plug of the keel strut has a wedge-shaped “crush zone” at its aft end inside the socket, and the keel structure is secured by pivot bolts near its center of gravity and “fuse bolts” at the forward end, designed to fail during a hard grounding. This system does away with the more conventional highly loaded vertical bolts for securing the keel to the hull.

The entire steel strut structure will be encased in a foil-shaped fiberglass external sheathing to provide the hydrodynamic lift that prevents leeway.

The result will be a new keel that weighs less than the old one, but also has a lower center of gravity to keep stability the same. It will have a smaller, thinner fin and a bigger bulb at the bottom than the original. End of story, this keel’s attributes both upwind and down, and the couple of thousand pounds saved in the keel and internal structure, will make Zemphira a dozen seconds per mile faster with a similar rating handicap, according to the computer modelling.

Time and space preclude me going into detail about the two special inch-and-a-half bolts with their spherical washers that the whole caboodle hangs on, and the twin “tension breakaway” bolts up front that have been calculated to fail at exactly a quarter second deceleration. Suffice it to say that Zemphira is the most complete testimonial to Bob Stephens’s ability to save the boat, and the day, in multiple respects. The design firm has worked with Lyman-Morse to ensure that everything new will perfectly mate, just beyond the extent of original damage, to everything old. And all of the new engineering fits below the cabin sole so as not to disturb the yacht’s gorgeous “living room” with its armchairs and raised paneling and masterpiece oval table.

It’s an example of a design office handling a major challenge with competence and ingenuity.

Contributing Author Art Paine is a boat designer, fine artist, freelance writer, aesthete, and photographer who lives in Bernard, Maine.

Goshawk/Zemphira

LOA: 76' 3"

LWL: 53' 6"

Beam: 14' 6"

Draft: 10' 9"

Displ.: 43,000 lb.

Sail Area: 2,000 sq. ft.

Power: 125-hp Yanmar

Sail Area/Displ. Ratio: 25.6

Displ./LWL ratio: 125

Designer

Stephens Waring Design

www.stephenswaring.com

Builders

Brooklin Boat Yard

www.brooklinboatyard.com

Rockport Marine

www.rockportmarine.com

Refit

Lyman-Morse Boatbuilding

Thomaston and Camden, ME

207-354-6904

www.lymanmorse.com

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.