Farewell to a Beloved Bridge

The falls and the now-demolished Blue Hill Falls Bridge, looking west into the Salt Pond. Photo by Ken Woisard

The falls and the now-demolished Blue Hill Falls Bridge, looking west into the Salt Pond. Photo by Ken Woisard

It’s not often that a manmade structure like a highway bridge makes a remarkable natural setting even more beautiful, but for generations Blue Hill area residents have felt that was their good fortune.

Since 1926, the concrete-arched bridge that spanned the reversing tidal falls two miles south of the village, weathered storms and flood tides, and inspired countless artists, photographers, and tourists to paint it, draw it, and photograph it. Kayakers and wake boarders traveled from far away to play in the rapids and standing waves created as the tides rise and fall, pushing water from Blue Hill Bay into the inlet known as the Salt Pond, then reversing course and flowing out.

Now the bridge is gone, its arch smashed by wrecking balls, the steel inside cut and hauled away in December 2022. A new bridge is being built to replace it, using the existing granite abutments. Most area residents agree that the new bridge will be safer and offer other advantages—such as pedestrian walkways on both sides. But the loss of the old one has sparked an outpouring of emotion.

A Facebook group dedicated to the bridge has provided one outlet. “This hurts my soul,” said one resident after photos of the half-demolished bridge were posted. “A sad day, dismembering an icon—goodbye, dear old friend,” wrote another.

“She was a tough old girl,” Denny Robertson, 82, a lifelong Blue Hill resident and former fire chief, said of the bridge. “She did a wonderful job for a long time. People around here loved her. It was almost a romantic thing.”

Psychologists have developed a name, “place attachment,” to describe the emotional feelings people develop for physical places like homes, neighborhoods, and structures. Disrupting place attachment can have a measurable negative impact on psychological well-being, researchers have found.

The now-demolished bridge was the fourth to span the falls. The first, built in 1851, was destroyed by a storm, and replaced by a second. Both were wooden. A new steel span built in the 1880s lasted until 1926, when the arched cement bridge officially called the Stevens Bridge took its place, carrying Route 175 traffic between Blue Hill and Brooklin, and points south. Its design was called a “through rainbow arch” because the roadway passed through the arch rather than passing over the top, and the arch’s shape looked like a rainbow. Since its December demolition, a temporary bridge has been erected a few yards to the west to carry traffic while the new span is built.

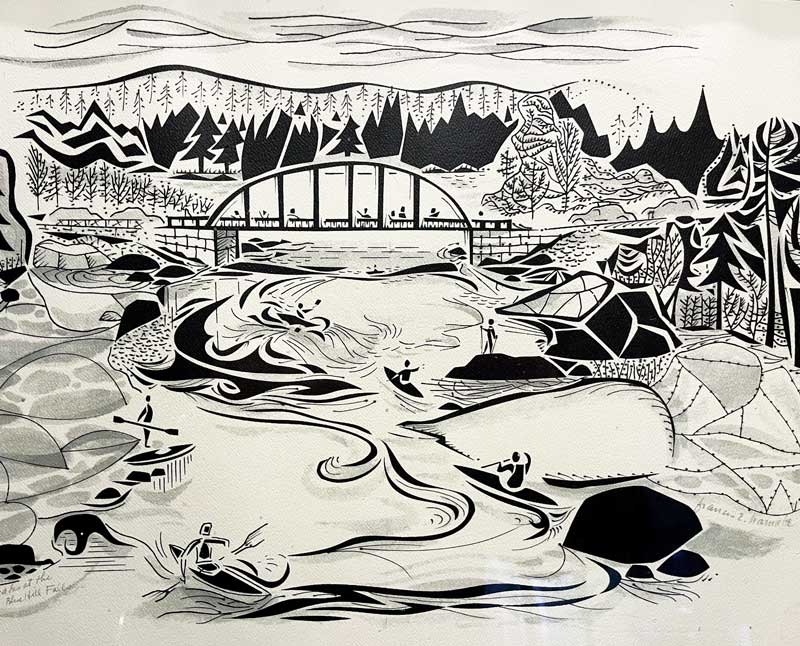

The late artist Francis Hamabe loved the falls, bridge, and activity including fishermen and kayakers. Drawing by Francis Hamabe, photo courtesy Steele Hays

The late artist Francis Hamabe loved the falls, bridge, and activity including fishermen and kayakers. Drawing by Francis Hamabe, photo courtesy Steele Hays

Long before any bridge at the site, the tidal falls flowed, and indigenous people gathered to harvest mussels and clams, hunt deer and moose, and fish for cod and other species. Just yards from the northern end of the bridge, along a hillside and rocky point into the bay is one of the most significant archeological sites ever excavated on the Maine coast—the Nevins site, named for the family that still owns land there. First explored in 1936-37, the site is both a shell midden and a burial site.

Among the artifacts found there were dozens of swordfish snouts, or rostra, from fish weighing as much as 1,000 pounds, indicating that the native people of the era were remarkable hunters, boatsmen, and navigators, using dugout canoes and bone harpoons to pursue their quarry. To fish for swordfish today, you’d have to travel far out to sea, but 4,000 years ago the marine environment was very different. Tide heights were only one to two feet, a fraction of the 9- to 13-foot tide heights today. Sea levels were significantly lower, and water temperatures were warmer, bringing swordfish closer to the shore.

The debate over whether and how to replace the bridge over the falls began in 2010 and lasted for 10 years. The town of Blue Hill formed an advisory committee to work with the Maine Department of Transportion (DOT) on evaluating alternative options and designs. One group advocated converting the bridge to a recreational site for pedestrian and boater use and rerouting the highway to cross the Salt Pond a half-mile south of the falls. After more than 30 hearings and meetings, the DOT announced that the best option was to replace the arched bridge with an enhanced girder bridge, four feet higher in elevation to accommodate sea level rise. The alternative route option would be too expensive, the DOT said.

State historic preservation officials signed off on the plan, saying that there was no risk to the archeological sites near the falls since the roadway would not change. The DOT agreed to erect an “interpretive panel” with information on the area’s archeological sites and on the history of human settlement in the area. In January 2022, the DOT awarded a $9.5 million contract for replacing the bridge to Cianbro. Work began in mid-summer.

Reflections in a tide pool accentuate the bridge’s graceful arch. Its design was called a “through rainbow arch” because the roadway passed through the arch rather than passing over the top, and the arch’s shape looked like a rainbow. Photo by Steele Hays

What makes a bridge beautiful? It’s a long-debated question. Part of the answer is how well a bridge fits its site. Are its proportions well suited? Does it appear balanced? Based on the thousands of times the Falls Bridge was painted, sketched, and photographed, most people felt it passed the beauty test. The new bridge will will be a state-of-the-art steel girder bridge with cast concrete panels on each side with a shallow arch shape and incised lines, or chamfers, designed to accentuate the shape.

Reflections in a tide pool accentuate the bridge’s graceful arch. Its design was called a “through rainbow arch” because the roadway passed through the arch rather than passing over the top, and the arch’s shape looked like a rainbow. Photo by Steele Hays

What makes a bridge beautiful? It’s a long-debated question. Part of the answer is how well a bridge fits its site. Are its proportions well suited? Does it appear balanced? Based on the thousands of times the Falls Bridge was painted, sketched, and photographed, most people felt it passed the beauty test. The new bridge will will be a state-of-the-art steel girder bridge with cast concrete panels on each side with a shallow arch shape and incised lines, or chamfers, designed to accentuate the shape.

Tim Cote, vice president with HNTB, the engineering firm that designed the new bridge, said this project was one of the most challenging he’s worked on in his 20-plus year career—based on the nearby archeological sites, the hydraulics of the tidal falls, the tight space available for maneuvering heavy equipment, and the diverse and strongly held opinions of area residents.

Building a new arched bridge was considered, but that option was ultimately rejected as too expensive and ill-suited for the short 100-foot distance the bridge needs to span.

“Aesthetically pleasing structures come in all forms,” Cote said in his email response to interview questions. “Some have design elements that make the structure a key focal point, while others have features that allow them to blend cleanly with the natural surroundings. Through our conversation with the community…we learned that what many folks truly valued at the Falls Bridge site was the natural beauty of the site. They wanted a bridge with aesthetics worthy of the surroundings, but that did not distract from the naturally beautiful vistas of Blue Hill Bay. To that end, a more subtle bridge design was developed with aesthetic fascia panels added to soften the lines of the structure and offer a more elegant appearance.”

One of the artists who painted and drew the Falls Bridge many times was Francis Hamabe, one of Blue Hill’s most revered artists. His former house, Wakonda, sits just north of the falls.

“Frank loved the falls and the bridge because there is so much life here,” said Jennifer Mitchell-Nevin, an artist and gallery owner who lives 100 yards from the falls. “He loved the sound of it, the sound of the water, the wildlife, the kayakers, the fishermen.”

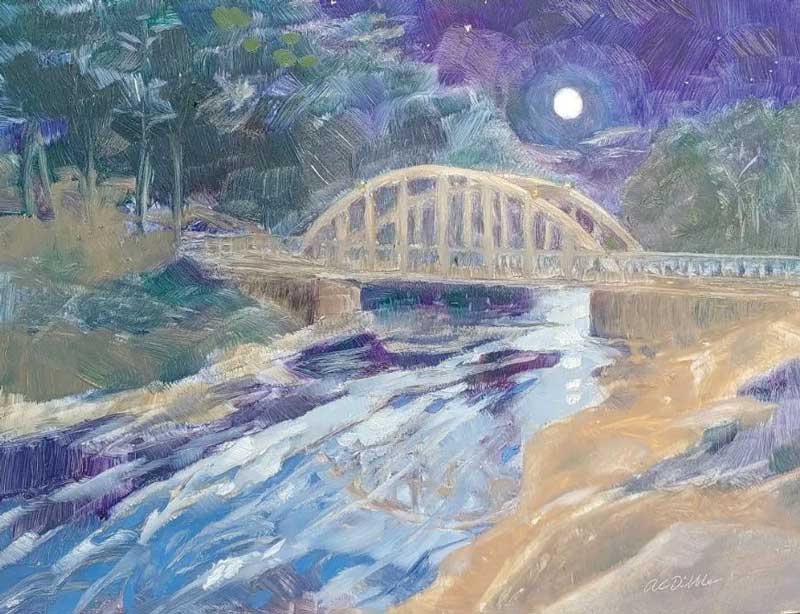

Full moon over the falls, a painting by Alison Dibble—one of many artists who have been inspired by the graceful old bridge. Painting courtesy Alison Dibble.

Full moon over the falls, a painting by Alison Dibble—one of many artists who have been inspired by the graceful old bridge. Painting courtesy Alison Dibble.

Artist Alison Dibble of Brooklin expressed similar sentiments. She has painted the old bridge more than 20 times, but said “I’m glad to see it go. It had very serious problems. The foundation was failing. Change is hard for people, but we will still have the falls and we’ll have a safer area. Safety is paramount.”

Andrew Lathe, the Maine DOT’s Falls Bridge project manager, has seen the community transition through the first four stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, and depression. Now that the 1926 bridge was been demolished, he argued that residents are at the last stage. They’ve accepted the loss and are focused on the positives—a wider, stronger, safer bridge with space for motorists, pedestrians, fishermen, bicyclists, birdwatchers, kayakers and artists to enjoy the falls and the views from the bridge.

Maine DOT’s rendering of what the new “enhanced girder” bridge will look like. Rendering courtesy Maine DOT

Maine DOT’s rendering of what the new “enhanced girder” bridge will look like. Rendering courtesy Maine DOT

When the new bridge is completed in late 2023 and the steel piles of the construction platform have been removed, the tides will continue to surge through the falls. They’ll flow slowly at first, then faster and faster, surging to peak speed and then slowing again and repeating the cycle. Ad infinitum.

✮

Steele Hays lives in Blue Hill and is a part-time marketing executive and writer. On still nights, he can hear the tidal falls from his house.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.