A Creative Revival

Innovative arts program sparks a rising tide in Eastport

Photos courtesy Tides Institute & Museum of Art

Seen above is artist Anna Hepler’s in-progress installation, which she described at the time as the hull of an empty ship in the nave of an empty church.

Seen above is artist Anna Hepler’s in-progress installation, which she described at the time as the hull of an empty ship in the nave of an empty church.

Eastport has become a lively center of arts and culture thanks in large part to an innovative non-profit that has bought and renovated historic buildings and brought visiting artists to the downeast community.

Since its founding in 2002, the Tides Institute & Museum of Art has acquired seven rundown buildings and transformed them into studios, galleries, performance spaces, and living spaces. The result is an astonishing hubbub of creative endeavor. Artists have converged on Eastport from around Maine, the nation and, indeed, the world.

Take Julia Sinelnikova, who is from New York City and has exhibited her work internationally. On a summer afternoon, she was working in a Tides Institute studio overlooking a harbor full of fishing boats. As a salt breeze wafted through the window, Sinelnikova cut patterns into a large piece of Mylar to create a light-reflecting three-dimensional work of art.

This small city steeped in downeast traditions is a far cry from the hustle and bustle she experiences in New York.

“I love going to remote locations around the water,” Sinelnikova said, explaining her decision to take up a residency here through the Tides Institute. “I have a meditative practice. I need a quiet place to pull my work together.”

The oldest church in Eastport, the North Church dates to 1819. The Tides Institute & Museum of Art is restoring and repurposing it as a 4,000 sq. ft. exhibition space.

The oldest church in Eastport, the North Church dates to 1819. The Tides Institute & Museum of Art is restoring and repurposing it as a 4,000 sq. ft. exhibition space.

Elsewhere, at various times of year and in various venues, Tides Institute-sponsored art installations fill whole rooms; artists ensconced in historic buildings produce sculptures and paintings, concerts and organ recitals, children’s programs, artist talks, and studio tours.

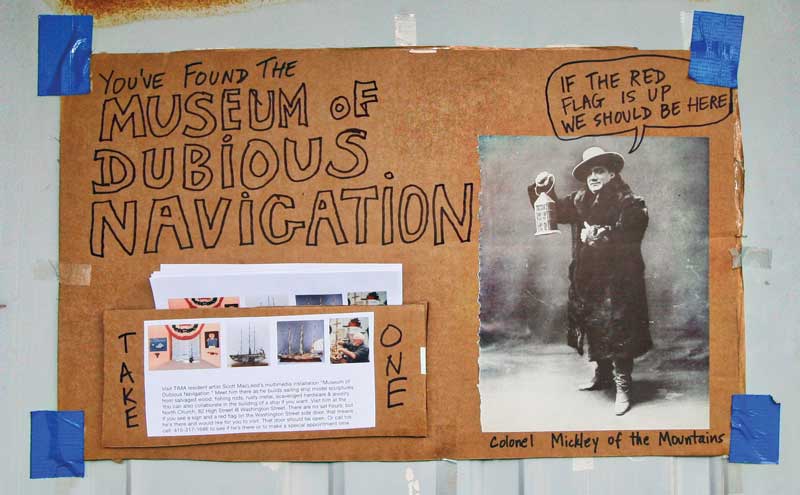

Scott MacLeod, a multimedia artist from Oakland, California, was working in the lower story of the North Church. Dating back to 1819, it’s the oldest church in town. The Tides Institute bought it as a part of an initiative to preserve historic structures and collections. MacLeod was transforming the space into what he called the “Museum of Dubious Navigation.” That included using found materials to produce ship models and other sculptures. He was surrounded by scrap wood, rope, and wire. Previous installations in other places have included a Museum of Useless Magic and a Museum of Bitter Sorrow, he explained. The latter, in Nevada was about prospectors—people who look but never find.

Visitors to his studio were welcome to view the work in progress.

“This was my number one choice, partly because of the insane wonderfulness that the website seemed to suggest, with these people who do all sorts of stuff,” he said.

“All sorts of stuff” pretty much sums up the Tides Institute’s creative ferment. These are not gift-shop artists producing ceramics decorated with lobsters. They’re exploratory, producing works that often challenge the viewer. The juried residencies are popular, drawing scores of applicants; a fraction is selected. In 2019, the program drew 13 artists, up from four in its first year in 2013. Each artist receives $2,000 for a four-week residency.

Multi-media artist Scott MacLeod created a “museum” in the North Church during his residency. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Multi-media artist Scott MacLeod created a “museum” in the North Church during his residency. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Artists like Sinelnikova and MacLeod are great illustrations of the Tides Institute’s outlook, said Kristin McKinlay, who cofounded the institute with her husband, Hugh French. “We’re looking for a different take or a challenge—something we haven’t seen before,” McKinlay said.

At the same time, the institute fosters interactions between artists and audiences.

“We want something where people come and say, ‘What is this Museum of Dubious Navigation?’” she explained. “It makes people think.”

The nonprofit’s campus includes seven historic buildings, ranging in date from 1819 to 1887, located within a few blocks of each other in the downtown and waterfront area. Each building has been renovated to host a wide variety of residencies, studios, galleries, and performances.

The Tides Institute & Museum of Art is headquartered in a historic bank building that had been slated for demolition prior to its rescue and renovation. It anchors one end of Eastport’s downtown.

The Tides Institute & Museum of Art is headquartered in a historic bank building that had been slated for demolition prior to its rescue and renovation. It anchors one end of Eastport’s downtown.

The organization’s collections range from historical to contemporary. They include paintings, prints, photographs, and sculpture; Passamaquoddy and Micmac basketry; architectural drawings, documentation, and artifacts; ship models; maps; decorative arts; musical instruments; graphic arts; and books, pamphlets, and ephemera.

Through cultural partnerships, additional projects range from extended studies of the area to the development of maps, cultural guides, historic resources, branding and promotional initiatives, and the creation of online resources—all designed to highlight Eastport and the region, past and present.

“Artists are coming from all over the United States and occasionally from other parts of the world,” said French. “That helps connect this area to the rest of the state, to the rest of New England, to the rest of the country.”

The organization employs one full-time person, two part-time, a paid intern, and a seasonal staff member. The annual budget of about $300,000 is funded by contributions, grants, and earned income.

Janice Wright Cheney, one of the organization’s artists in residence, works on her “Sardinia” installation at the North Church Project Space building.

Janice Wright Cheney, one of the organization’s artists in residence, works on her “Sardinia” installation at the North Church Project Space building.

On Maine’s far eastern coast, Eastport has a history as a trading and fishing hub. The sardine industry once thrived here, with hundreds of people employed by canning factories and curing houses that ran day and night. When fishing declined, people moved away, and buildings were boarded up.

“This area was overlooked for any number of reasons, in part because it isn’t well-known,” said French.

French is an Eastport native. His mother, Winifred, started the local newspaper, The Quoddy Tides, which his brother Edward French now runs. Early in his career, he received a National Endowment for the Humanities “Youth Grant” to curate an exhibit on the history of the Eastport waterfront. French subsequently worked at the Salt Institute for Documentary Field Studies in Portland, Maine.

McKinlay, who is from Chicago, attended college in Maine and met French in Portland. They returned to Eastport with the idea of making a difference in a community in decline. Both were interested in collecting and preserving artifacts that represented Eastport’s history. They started the Tides Institute as a website.

The North Church Project Space building is still undergoing restoration. It is shown here at dusk during an art installation opening.

The North Church Project Space building is still undergoing restoration. It is shown here at dusk during an art installation opening.

“We knew we’d have a physical center at some point,” said McKinlay. “But first we were looking to get feedback from funders and organizations. It was a fledgling effort to put ideas out there and see what people had to say.”

The emphasis was on forging connections in the community and with agencies and funders.

“This is not something we could have done on our own,” she added. “There’s a lot of collaboration.”

Eastport has a history as a trading and fishing hub. This photo, which is in the Tides collection, was taken by Cecil Greenlaw and shows herring boats along the waterfront in the 1930s. Photo courtesy Tides Institute & Museum of Art

Eastport has a history as a trading and fishing hub. This photo, which is in the Tides collection, was taken by Cecil Greenlaw and shows herring boats along the waterfront in the 1930s. Photo courtesy Tides Institute & Museum of Art

Then a historic downtown building caught their attention. Built in 1887 as Eastport Savings Bank, its exterior was warped and people were afraid it would fall. The city called for demolition.

The institute acquired it in 2002.

“If we hadn’t jumped in, it would have been destroyed,” said French. “We took a big leap of faith. We had very little money behind us.”

Extensive fundraising and renovation resulted in a rejuvenated gem that now houses the institute’s offices and collections. Other restorations followed, as the institute purchased or was given various 19th century buildings and other properties. Residents were skeptical of some projects, but elbow grease boosted the organization’s credentials. At one abandoned church, “people saw mold and said, ‘Tear it down,’” McKinlay recalled. “We said, ‘No, we’re going to get gallons of vinegar and wash it and fix the plaster.”

Downtown activity grew in kind, with an infusion of infrastructure grants and an influx of galleries, shops, and eateries. Eastport Breakwater Gallery co-owner Michael Morse recalled arriving in 2004, a time when most of the downtown was boarded up.

“But we knew there was potential,” Morse said. “When we bought this building, we were the only business on the block. Within two years, it started filling in.”

Hugh French, an Eastport native, and his wife Kristin McKinlay started the institute as a website and grew it to an organization that has helped revitalize many of Eastport’s historic buildings and its cultural scene. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Hugh French, an Eastport native, and his wife Kristin McKinlay started the institute as a website and grew it to an organization that has helped revitalize many of Eastport’s historic buildings and its cultural scene. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Development grants helped transform the downtown, Morse noted. Today, it’s a busy hub of activity.

“There was a feeling that there was an opportunity there, that some things were possible that might not have been possible at any other time,” French recalled. “We’ve shown that this area isn’t an unknown and it isn’t a backwater. Significant, interesting, exciting things happened here in the past and continue to happen now.”

MBH&H Contributing Editor Laurie Schreiber is also a Mainebiz staff writer and has covered topics in Maine for more than 25 years.

For More Information:

Exhibition schedules, residency information, and past projects are available at for The Tides Institute & Museum of Art site at www.tidesinstitute.org.