En Plein Mer with Amy and Seamus Hourihan

Photos of paintings courtesy the artist

The Maine coast is her muse: Amy Hourihan set up to paint on the eastern shore of Roque Island way downeast. Photo by Sally Reiley

The Maine coast is her muse: Amy Hourihan set up to paint on the eastern shore of Roque Island way downeast. Photo by Sally Reiley

One day, while painting a watercolor of Manana, Monhegan’s nursling island, Amy Hourihan accidentally dropped a favorite sable paintbrush overboard. “It began to bob, hair side up, toward the channel,” she recounted. The skipper, her husband Seamus, and a crew member lowered the inflatable and gave chase while she pointed at the rogue brush from the coach roof. In retrospect, she noted, it was a “good man overboard drill.” And to this day the brush remains “a great tool in the hand” when she paints.

Hourihan, née Colbert, grew up in Rye, New Hampshire, where her family ran an equestrian stable. She attended the Mary Hitchcock School of Nursing in Hanover, and later trained as a nurse practitioner. She has always been a watercolor “dabbler,” but she threw herself at it about 20 years ago when her children, Tim and Kate, were teens and she had more time on her hands. She took classes with Boston-based watercolorist and printmaker Joel Janowitz, who spends part of each summer painting on Great Spruce Head Island. She credits him with giving her a “new lexicon” for expressing the Maine landscape.

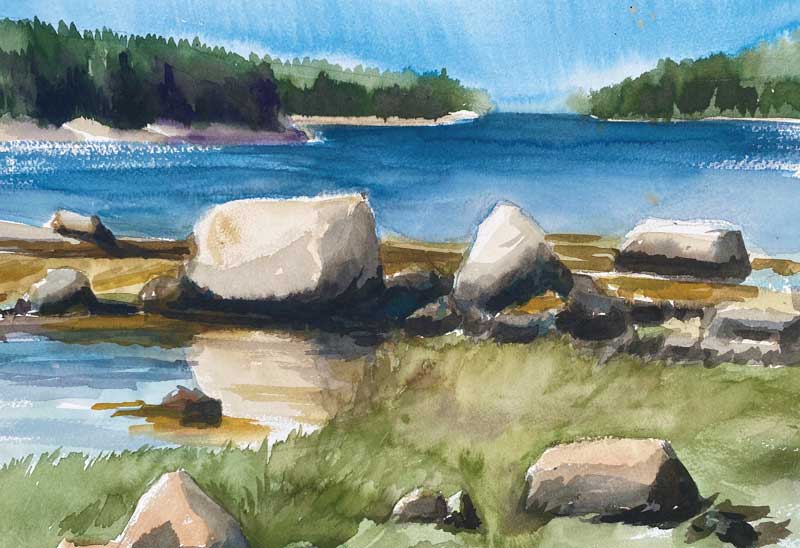

Hourihan’s plein air watercolors feature color washes and reflect a sense of place. Roque Island, 2022, watercolor, 11 by 14 inches.

Hourihan’s plein air watercolors feature color washes and reflect a sense of place. Roque Island, 2022, watercolor, 11 by 14 inches.

The study has paid off. Hourihan shows her watercolors and prints with art associations and collaboratives around Boston’s North Shore and has taken top honors in a number of regional and national juried exhibitions. Her artwork is featured in the Boston Athenaeum’s Charles River alphabet and appears on the labels of several beers brewed by True North Ales in Ipswich.

Around the same time she became serious about painting, Hourihan began taking a watercolor kit and drawing supplies along on sailing cruises—have boat, will paint. Her compact plein air set-up, recommended by another Boston artist-teacher Gary Tucker, includes a folding SHY watercolor palette with deep wells for mixing washes and a lightweight adjustable SunEden easel that snaps onto a standard photography tripod that holds the block of paper, usually cold-pressed Arches, in place.

Thirst, the Hourihans’ Gunboat 55 catamaran, under sail. Their record for a 24-hour passage: 290 miles under sail, averaging 12 knots. Photo by Martha Altreuter

Thirst, the Hourihans’ Gunboat 55 catamaran, under sail. Their record for a 24-hour passage: 290 miles under sail, averaging 12 knots. Photo by Martha Altreuter

Hourihan is part of a long and rich tradition of artists who have found their subject matter from a floating perspective. One thinks of Fitz Henry Lane who cruised the Maine coast from his home in Gloucester, painting scenes of Castine, Southwest Harbor, and other ports of call along the way. More recently, Michael Weymouth has drawn inspiration from cruises in Penobscot Bay, painting islands and the coast (some of his images appear in Elizabeth Garber’s book Maine: Island Time).

Sailing into a harbor in late afternoon, Amy and Seamus will row to shore and while he goes for a walk, she paints. On a recent trip downeast, they motor-sailed into Shorey’s Cove on Roque Island to get out of rain showers and wind. When the pea soup fog burned off the next morning, they pulled up the anchor and moved to the eastern anchorage. There Amy set up on the beach to capture a view of the curving strand accented with seaweed.

Over the years McGlathery Island off Stonington has become a favorite place to go ashore and explore. “Painting the glacial erratics there has become a bit of a tradition for me,” Amy noted. “The great stones seem deliberately placed by an unseen hand, much like elements of a Japanese garden.”

On longer passages, Amy will paint on the boat, after they’ve set sail and expect to hold a heading for a while. “People always are incredulous when I tell them that I can easily paint when the boat is under sail,” she reported, “but catamarans do not heel over very much, and our main salon has a sturdy table and chairs where I can work.”

Amy is attracted to late afternoon light as it rakes across “the quintessential landscape” of spruce trees, granite rocks, and the intertidal zone. The cloud formations prompt her to paint as well. “The humid summer days in Maine, the lifting fog, the choppy surf, all create incredible atmospheric conditions,” she said.

When their children were small, Bucks Harbor was a frequent port of call because they were so familiar with Robert McCloskey’s children’s books. Since then, they have visited many harbors and islands between Biddeford Pool and Campobello Island and even sailed up the St. John River in New Brunswick.

Amy Hourihan, Jonah Crabs, 2022, watercolor, 7 by 10 inches.

Amy Hourihan, Jonah Crabs, 2022, watercolor, 7 by 10 inches.

The couple’s earliest sailing adventures on the Maine coast took place in the 1980s, cruising with Seamus’s parents on their Hunter 37. They have always preferred the uncrowded anchorages, reliable breezes, and uninhabited islands of Maine to the much more frenetic experience of Buzzards Bay, the Cape, and Islands. “Given our druthers,” Amy said, “we point the boat northeast.”

In the early 1990s they bought their own racing cruising boat, a J/120 called Ruffian. They sailed in the annual Eastern Yacht Club Cruises, racing point to point, and enjoyed the on-shore festivities. Seamus remembered one particularly wild race up Somes Sound. It was very windy and the crew “was tacking the genoa every minute or two as they headed southwest and up wind back to the finish line.”

The Hourihans launched Thirst, a new Gunboat 55 catamaran, in Wanchese, North Carolina, in 2016 after a two-year build. The 55 is the largest of the Gunboat designs that still can be handled by an experienced couple without additional crew. (Gunboat’s assets were bought in 2016 by a French company and the boats now are built in France.)

They had been looking for a fast, comfortable boat that would be fun to sail with friends and family. Additionally, Seamus wanted a craft capable of performing well on the racecourse and that could “bang out the miles” quickly on long deliveries. Their record for a 24-hour passage is 290 miles under sail, with an average of 12 knots. The boat can leave the Virgin Islands or Antigua and be back in Marblehead, its home, in roughly a week.

And the name? The early Gunboats launched by company founder Peter Johnstone all seemed to have cryptic, one-syllable names such as Cream, Tribe, and Elvis, and the Hourihans wanted to follow suit. Thirst seemed like a good name to go with their state of mind in early retirement. “Thirst is also a reference to our human nature to always be hankering for something new, innovative, yet to be realized, just out of reach,” Amy explained, adding, “a thirst for adventure, speed, comfort, libations, and more.”

The boat also builds character. “There aren’t bad days in Maine,” Amy noted, “but making passages in a 25-foot-wide catamaran, in fog, through fields of lobster pots will test any marriage.” Which one to avoid, the pink and black pot with a toggle on starboard, or the flagged fishing net mark directly on port? “Often the answer is unavoidable: to put a lobster pot squarely between the hulls and watch anxiously for it to bob up behind us.” They try hard to protect the fishing gear they encounter.

Hourihan likens the boulders on McGlathery Island off Stonington to rocks in a Zen garden. McGlathery Erratics, 2021, watercolor, 9 by 13 inches.

Hourihan likens the boulders on McGlathery Island off Stonington to rocks in a Zen garden. McGlathery Erratics, 2021, watercolor, 9 by 13 inches.

Amy had never sailed until she met Seamus. Born in Marblehead, he had learned to sail at the Children’s Island Day Camp and then the Pleon Yacht Club. He started at age 10 with his younger brother John and his father who was “a stinkpotter at heart.”

As far as sailboats go, the Hourihan family first had a 16-foot Town Class sloop designed in 1935, which they raced actively in Marblehead. They competed against 30 or more boats on the weekend and nearly 60 boats in two divisions during Marblehead Race Week.

Eventually Hourihan père stopped racing, leaving it up to his boys to carry on. Which wasn’t always tranquil: “More than once my parents found the boat luffing,” Seamus recounted, “with my brother and I fighting because we disagreed where to go.”

Seamus went to local schools through high school. At Dartmouth College he majored in visual studies and architecture but shifted gears, enrolling at the Olin Graduate School of Business at Babson College. For 35 years he worked in computers and networking products, helping to start a few companies, two of which went public.

The building of Thirst represented a lifelong dream, the ultimate getaway. To watch Seamus at the helm is to witness a sailor in his element, calling out orders, peering back over his shoulder as the boat makes its way downeast.

In recent years the Hourihans have been spending more time in Maine on terra firma. Their son Tim and his partner Sydney Gross run Top Blossom Farm, a small-scale farmstead in Dresden, Maine. According to its website, Seamus is the resident “Mr. Fix It” while Amy assists with flowers and the nursery.

They’ve also recently became grandparents. Their daughter Kate and her family live in Seattle so they’ve been going west to visit and to start grooming the next generation to take to the waves and waters of Maine—and maybe one day paint their way down the coast.

In 2021 Carl Little received a Lifetime Achievement Award for his art writing from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.

You can see more of Amy Hourihan’s artwork at www.amyhourihan.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.