Cormorants of Marblehead Island

A mild-mannered adventure in search of a miraculous seabird.

Double-crested cormorants have iridescent black plumage and an orange pouch around their beak. During breeding season, they grow tufts of feathers on their heads. Photograph by Daniel Roby.

By Richard J. King

Double-crested cormorants have iridescent black plumage and an orange pouch around their beak. During breeding season, they grow tufts of feathers on their heads. Photograph by Daniel Roby.

By Richard J. King

Due to bookish ways and too much time spent e-mailing, I was in need last summer of a little watery adventure. I’m especially fond of reading accounts by the early naturalists—those men who set out under sail, battled around frozen Cape Horn, then canoed through foreign marshes while dodging spears whizzed at them by naked cannibals in order to bundle up a sample of a new species of razor clam to donate to the Museum of Natural History. I was looking for something like that.

One afternoon in the stacks of the university library, I happened upon a dusty little volume titled The Home-life and Economic Status of the Double-crested Cormorant, by Howard L. Mendall. It was published by the University Press of Maine in 1936.

Though cormorants, often known as shags (or much worse), tend to ignite the ire of so many Mainers, I have a disproportionate fondness for them. Maybe I wouldn’t be dodging spears, I thought, but revisiting Mendall’s work might lead to a mission at sea.

An Odd Little Bird Book

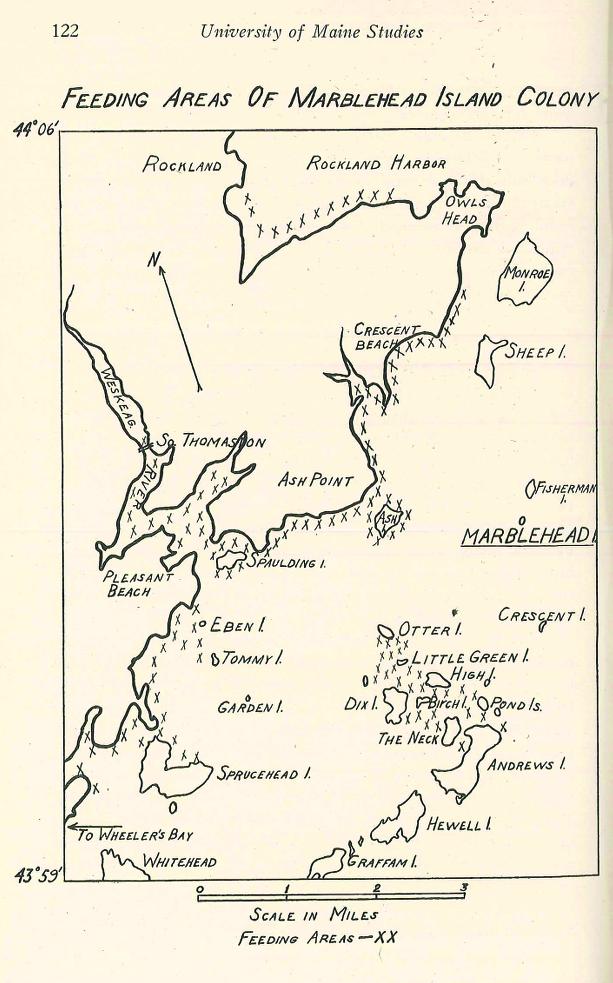

Mendall’s book is based on his study of about 350 pairs of double-crested cormorants nesting on Marblehead Island, a tiny rock clump south of Owls Head, Maine. Marblehead was one of the first islands in Maine to see the return of these nesting birds in the 1920s. This was after cormorants had been extirpated from the state due to human disturbance and persecution on their island rookeries, including people hunting the birds and their eggs for bait and food.

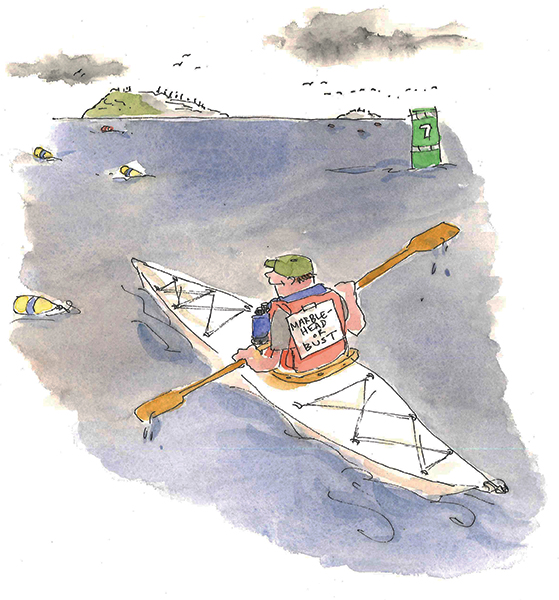

Illustration by Richard J. King.

Few birds of this continent have been so little understood as cormorants. Mendall wrote: “They are loosely related to the gannets, pelicans, man-o’-war birds, and other members of the order known as the pelicaniformes or totipalmate swimmers.”

Illustration by Richard J. King.

Few birds of this continent have been so little understood as cormorants. Mendall wrote: “They are loosely related to the gannets, pelicans, man-o’-war birds, and other members of the order known as the pelicaniformes or totipalmate swimmers.”

Cormorants are those black waterbirds with the long thin beaks, known for their habit of standing with wings outstretched on a piling or a sea-splashed rock. “Totipalmate” means they have four webbed toes, rather than the more common three-toed webs of gull feet. Cormorants swim under water using their wide feet like paddles, as opposed to other diving birds such as penguins or puffins that prefer to use their wings under the water’s surface. Double-crested cormorants can dive to at least 25 feet, but probably even much deeper. More than one lobsterman has told me of cormorants caught in pots set as deep as 100 feet. Cormorants in other parts of the world—there are about 40 species living near almost every major body of water on earth—have been tracked diving to more than three times even that depth.

Throughout his account, Mendall printed tables and graphs, dutiful observations of bird behavior, and careful measurements of eggs and nests. Occasionally, though, he tucked in little anthropomorphic dainties of his observations of breeding cormorants. “Rubbing of breasts between the paired birds is also of very frequent occurrence, and the whole performance is accompanied by low croaks and deep gurgling notes,” he wrote. “Frequently I have seen mated cormorants continue to spend several minutes at a time doing nothing but showing affection long after their young had left the nest.”

Rubbing of breasts between the paired birds is a very frequent occurrence, and the whole performance is accompanied by low croaks and deep gurgling notes. Photograph by Adam Peck-Richardson

Rubbing of breasts between the paired birds is a very frequent occurrence, and the whole performance is accompanied by low croaks and deep gurgling notes. Photograph by Adam Peck-Richardson

Howard Mendall spent his career doing wildlife research in Maine, which named a state wildlife management area after him. This photo was taken in 1948. Courtesy Special Collections, University of Maine Raymond H. Fogler Library

Howard Mendall spent his career doing wildlife research in Maine, which named a state wildlife management area after him. This photo was taken in 1948. Courtesy Special Collections, University of Maine Raymond H. Fogler Library

Born in Augusta, Maine, Mendall graduated from the University of Maine with a degree in zoology and was in the middle of getting his master’s degree there when he spent three summers studying cormorants on Marblehead from 1933-1935 with his “chief assistant,” his wife Emma. In their early twenties, the couple crouched in little tents to observe the mating rituals of cormorants and how they raised their young. The Home-life and Economic Status of the Double-crested Cormorant was Mendall’s first major publication. He went on to devote his life’s work to teaching and writing about ornithology and ecology and conducting wildlife research for the state of Maine for more than a half century.

Mendall describes one particular evening on Marblehead—July 2, 1934—during which he stayed up throughout the night and recorded the events of the cohabiting cormorant and gull rookery. Cormorants sleep more or less from sundown to sunup. Gulls are more vocal and sleep lightly. His notes include the following:

“1:30, young cormorants are quiet throughout the colony. 1:50, a faint yellowish glow is appearing in the northeast and I think dawn is beginning. 1:55, the Boston steamship is going by and apparently the noise of engines awakens the Gulls as they are shrieking in loud tones and in increasing numbers. Cormorants are still quiet, however. 2:20, a couple adults on the side nests are grunting to their young which have awakened. 2:30, it is getting fairly light now, and Fisherman’s Island [a larger island just to the north] is a bedlam of noise. F [nest] young are awake and snapping at each other. 2:45, a few adult cormorants are flying over the island. It is quite light and the northeastern sky is colored a beautiful orange.”

Marblehead Island or Bust!

Mendall’s study of a cormorant island in Maine sounded perfectly quirky and lovely. It croaked of just the sort of oddball, mild-mannered adventure for which I’d been hankering. I told my wife (read: she didn’t want to play Emma Mendall, but she gave me permission) that on a whim, it being early summer and the cormorants nesting, I was going to drive up to Maine right away (read: she suggested an upcoming Tuesday that would be most convenient), and I’m going to kayak out to blustery, lonely Marblehead Island (it’s less than two miles from the well-developed coast and nearly swimming distance to other islands) and observe these cormorants firsthand.

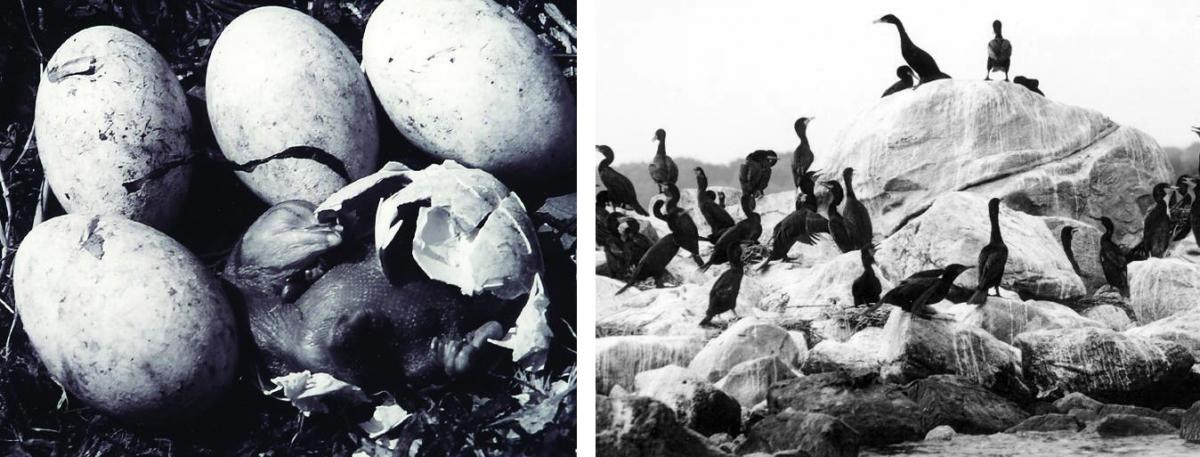

Double-crested chicks emerge from the egg and commence living colony life on a New England island. Photographs by Richard J. King

Double-crested chicks emerge from the egg and commence living colony life on a New England island. Photographs by Richard J. King

The morning of the next convenient Tuesday, I pulled out of the driveway in our Volkswagen mini-bus, which was dwarfed beneath the huge Greenland-style kayak that I had built in a class years ago. Bound toward Rockland with our dog Ruby by my side, I felt ever so slightly, uncharacteristically, rugged. It didn’t matter that this pursuit of a first-hand experience with cormorants was both undefined and not exactly as sexy as, say, bow hunting for elk—or even as significant as seeking out a photo of a rare warbler. But why not learn a bit more about the common, the overlooked?

Twenty minutes into the drive I realized that although I’d printed out directions, slipped the relevant section of a marine chart in plastic, and packed Mendall’s book, I had forgotten the entire bag.

“Bah! I’ll be fine,” I said aloud. “I’ve got a road atlas. I’ll figure it out. Right, Ruby? Cormorants, I’m on my way!”

Ever since European settlement, conflicts have erupted across North America over cormorants eating fish that people believe they shouldn’t or cormorants depositing their guano in areas where people wish they wouldn’t. Harassment of these quiet, black birds has resulted in population rollercoasters, usually as result of man’s own ironic, heavy hand. We’ve killed them indirectly with overfishing and the reduction and pollution of coastal habitats. We’ve also promoted cormorant populations in other locations by building mammal-free rookeries beside natural fish runs and developing open-air aquaculture sites next to their natural flyways. Cormorants, along with all other seabirds, have been federally protected since 1972.

The longest history of persecution of cormorants in North America is predictably along the New England coast. Part of Mendall’s mission on Marblehead Island in the 1930s was to determine to what extent cormorants were competing with commercial fishermen. He concluded that they simply were not. Regardless, state wildlife managers proceeded to suffocate more than 188,000 cormorant eggs with oil between 1944 and 1953. Still the numbers of double-crested cormorants along the Maine coast continued to rise gradually, despite culling programs, coastal pesticides, and the shooting of birds to keep the animals away from hatchery-released salmon smolts. As in other parts of the country, double-crested cormorants along the coast of Maine reached their peak in the 1980s and early 1990s, in part thanks to environmental protections and water quality improvements. Their numbers have since declined. According to Brad Allen at the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, bald eagles have been a major cause for the recent drop in the Maine population of cormorants by nearly half. Eagles swoop into cormorant rookeries and eat their young.

To my surprise, I made it to Rockland in reasonable time and found the dead end at Ash Point. There was still plenty of daylight, and the sea was calm, but the weather report threatened heavy thundershowers, even hail.

I’m an adventurer, right? Right, Ruby? While carrying the kayak down to the beach, I met an attractive younger woman who was going for a swim. I asked her how private this beach was—meaning, is it okay to launch here—and she nodded that it wouldn’t be a problem. Surely she was a bit tongue-tied: impressed with my whole rugged middle-aged scene.

I put Ruby back in her beloved van with the windows open.

Binoculars. Camera. Paddle. Life jacket. Bilge pump. VHF radio. I lifted the kayak down over the cobblestones to the waterline. I saw what I thought was Marblehead on the seaward side of Ash Island: a little ramp of rocks with green shrubs on the higher, north end, and white, guano-stained rocks on the lower half.

Originally I had considered camping out on Marblehead and replicating the night-long observation of the colony, but then I learned the island is owned by the state of Maine for conservation. It also turns out that it’s a bad idea to walk around a seabird colony while the birds are nesting. Cormorants are skittish with people. They’ll fly off and leave their eggs or chicks vulnerable to gulls (or eagles), which will swoop in to gobble up an easy snack. To reduce any disturbance, Mendall had a pre-constructed blind in which he could hide as soon as he got ashore.

Content with just a trip to see the island from a safe distance, perhaps to see a cormorant fledgling or a cormorant sitting on a nest, I climbed into my kayak and slid into the ocean. No thunderclouds in sight.

Accompanied by a soft southwesterly breeze, I paddled cleanly, but with power, hearing that salty sound of the wood through the water and the drips pattering off the paddle. I looked back to check my track off the beach, and then noted the pull of the current on the lobster buoys—because I’m an intrepid mariner who knows to log all variables.

Almost immediately I was rewarded. A double-crested cormorant flew from the left, low and earnest. As it veered closer, I saw that it was bigger than I realized, practically a turkey vulture, winging deliberately just over the surface of the ocean. I fumbled around with my binoculars and camera and then put them down just in time to see the bird whoosh nearly over my bow. The cormorant was decked out in its finest feathers for, as Audubon used to call it, “the love season.” The rich black plumage was iridescent. In the low sun as the bird zoomed past, the shades of green, purple, and gold shimmered across its belly, chest, and neck. The two tufts of black feathers off the head—the derivation of its common name—were blown aft. The skin between the head and beak was as crimson as my life jacket. The mouth parted slightly as it flew, revealing the aqua blue skin of its gape. The wings made a squeaking sound, as if they could stand a drop or two of oil.

I was breathless and feeling even somewhat magical, seeing that bird so close, as if he (or she?) buzzed my bow as a welcome—or a warning.

The Black Tempest

Paddling in the lee of Ash Island, I now saw two islands covered in white guano. Without a chart, I wasn’t sure which was Marblehead.

Marblehead Island is a rocky bump just off Ash Point near Owls Head. The Xs on the map from Mendall’s 1936 book show cormorant feeding areas. Courtesy University of Maine Press

The breeze began to pick up. Was that because I was out of the protection of Ash? Did those clouds over my right shoulder look darker? I steered behind a green bell buoy that was clanging with the long swells, the same seas that sloshed over my cockpit. I looked back at the beach, then at my watch, and committed to paddling just 10 more minutes. My binoculars have a compass, so I took a bearing back to a point on shore in case, I told myself, the storm was so violent that I couldn’t see the coast anymore. The breeze seemed fuller, the swells a bit steeper. That cloud mass loomed darker.

Marblehead Island is a rocky bump just off Ash Point near Owls Head. The Xs on the map from Mendall’s 1936 book show cormorant feeding areas. Courtesy University of Maine Press

The breeze began to pick up. Was that because I was out of the protection of Ash? Did those clouds over my right shoulder look darker? I steered behind a green bell buoy that was clanging with the long swells, the same seas that sloshed over my cockpit. I looked back at the beach, then at my watch, and committed to paddling just 10 more minutes. My binoculars have a compass, so I took a bearing back to a point on shore in case, I told myself, the storm was so violent that I couldn’t see the coast anymore. The breeze seemed fuller, the swells a bit steeper. That cloud mass loomed darker.

I wasn’t going to make it to Marblehead in 10 minutes.

So I rationalized that it was not the fear of getting flipped or losing my paddle or getting fried by lightning. No, I turned back because poor Ruby might be getting nervous. And even the most intrepid of naturalists knows about living to explore another day.

As I paddled back around Ash Island, the breeze seemed to have settled. Those clouds looked like they’d cleared. A flock of eiders rested on the water. I floated over to calmer waters closer to the mainland. Two bald eagles perched on top of the tallest fir tree on Ash Island.

I kept paddling, now reluctantly, back to the beach. I saw a few more cormorants flying along the coast, but none toward Marblehead.

Then one cormorant pulled up and landed near me. It dove under water for a few moments before popping back up closer to the beach—seemingly without a fish—and then leaped out, smacked the water with its feet, and flew off on a line drive.

Back on the beach, I lugged the kayak above the tide line. While taking Ruby for a walk, I met an old codger walking on the rocks. When he asked what I was doing here, I explained that I’d come to see the cormorants of Marblehead Island.

He shook his head. “Damn shags. Black water rats. Good for nothing but bait. You know, we used to use ’em to catch cod. Shag meat held up pretty good underwater.”

He bent down to pet the dog. “Never understood bird watching.”

A cormorant flew past, just inches over the water.

Seeing this, the man added: “Black cats of the water, those devils. See one cross your bow and a storm’s on the way.”

Ruby and I watched him walk off. I collected some rocks for my daughter, then drove off for a pizza. I returned to watch the sun set on the islands. It got dark fast. Ruby huddled at my feet, and a breeze began to whip the surface of the bay. A startling lightning bolt lit up the islands. The clouds emptied rain by the buckets as the thunder rolled. I felt somewhat vindicated for being so wimpy in the kayak.

Consider the Cormorant

Disappointed with myself for not defending the cormorants in front of the ancient mariner, I remembered how Mendall finished his book: “An attempt is made to point out that the [cormorant] is fully deserving of our protection and that, except in scattered, local instances, it is largely neutral if not actually beneficial in its relationship to man.”

I’ve learned that cormorants, like all wild seabirds, are a positive indicator of a healthy environment. Cormorants are not invasive or alien. Early explorers in New England wrote of abundant cormorant rookeries. Cormorants do not eat dead materials or human trash. Since they are opportunistic and prey on a wide variety of fish and crustaceans, they can help correct imbalances caused by introduced species. While they certainly might eat small lobsters, salmon smolt, and commercially caught fish, they also eat the same fish that prey on these desirables.

Sitting in my van that night, with the rain pelting the kayak on the roof, I wondered what other family of animals can fly, walk, swim under the surface, and live in warm and cold climates, as high as the mountains or at sea level, and in fresh or salt water? Some 165 pairs of double-crested cormorants—about half the size of the colony Mendall observed 60 years ago—were huddled over their nests out there on the island without cover. What were those dark silent birds doing out there on Marblehead Island in this thunderstorm? How do they protect their chicks? Maybe I'll return one (convenient) day next summer to find out. I'll remember the chart. And get a bigger boat. With a stout anchor.

Richard J. King is the author of Lobster and The Devil’s Cormorant: A Natural History. He teaches Literature of the Sea at the Maritime Studies Program of Williams College and Mystic Seaport.

The Double-crested Cormorant in Maine

Bigger than a duck and smaller than a goose, adult double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) weigh between 3 and 5 pounds. They can eat, depending on the time of year and other factors, roughly a pound of fish a day from a wide range of fish and crustaceans.

Double-crested cormorants have black, iridescent plumage, and an orange gular pouch. For a few weeks a year when breeding, they have two tufts of feathers on their heads. Juvenile and non-breeding adults have light-brown breast feathers. Unless you’re the likes of Howard Mendall, it’s very difficult to tell the difference between a male and a female. The female cormorant has identical plumage, but is slightly smaller.

Cormorants in Maine construct their nests primarily with sticks, seaweed, eelgrass, fish skeletons, and often man-made items such as rope, lobster trap parts, and plastic pens. The birds generally lay two to five chalky, pale-blue eggs each summer, not all of which survive. Although there is a record of a double-crested cormorant living more than 17 years in the wild, living to about six is probably most common. Cormorants nest on rocks or on trees, and forage in a wide range of habitats, including freshwater lakes, rivers, marshes, and rocky ocean habitats.

Double-crested cormorants nest in 43 states in the spring and spend time in every one except Hawaii. In Maine today, about 9,800 pairs of breeding adults nest in some 80 colonies along the coast, with just one small colony inland, at Moosehead Lake.

From afar, cormorants can look like loons (which do not have a hooked end of the beak and have stouter, shorter necks). Six total species of cormorant live in North America. The other found in the northeast, the great cormorant (P. carbo), breeds in very small numbers in Maine, but is now a fairly common winter resident, migrating down from Canada. Great cormorants are larger, have a line of white on the face, and a patch of white feathers on the thigh. The double-crested cormorants from Maine winter in areas such as the Gulf Coast and the Florida Keys. —RJK